Tuesday, October 18, 2016

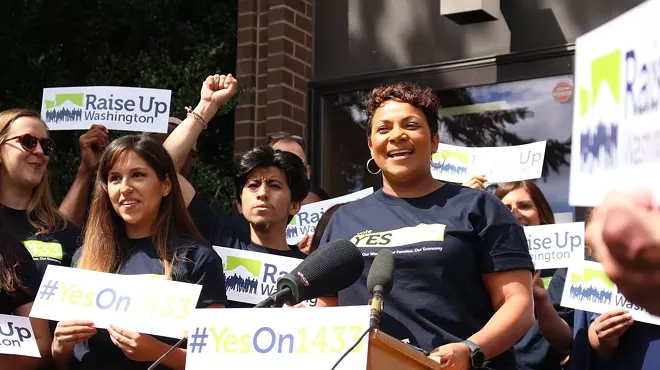

How Seattle's $15 minimum wage kneecapped opposition to statewide wage hike

If polls and campaign contributions are anything to go by, Washington state — which, at $9.47 already had one of the highest minimum wages in the country — is about ready to boost its minimum wage to $13.50 by 2020.

This month, a KOMO News/Strategies 360 poll found the Raise Up Washington initiative, which would also guarantee sick leave for all workers, was leading with 62 percent supporting.

And the cash difference was even more dramatic: As of last week, over $3.3 million in cash contributions had been raised for Raise Up Washington. That's more than 50 times as much as the anemic $66,500 in cash raised by the No on 1433 campaign.

It's

But despite this initiative applying to the entire state of 7 million, opponents have only raised about a tenth of that this year. The wind appears to have gone out of the opposition.

Some of that could be simply the fatigue of defeat: Why dump money into a cause you'll probably lose?

"They see the same polls we see," says Jack Sorensen, spokesman for Raise Up Washington.

Yvette Ollada, the spokeswoman for the "no" campaign, suggests many concerned businesses know they won't be able to compete with initiative funders like billionaire venture capitalist Nick Hanauer.

"Businesses are strapped," Ollada says "If we lose and it passes we need to figure out how we're going to keep the doors open."

But there's another big factor worth considering: Seattle, thanks to a city council vote in 2014, is already on the road to gradually increasing the minimum wage of all businesses to $15 an hour by 2021.

So while Raise Up Washington's provisions would increase sick-leave requirements for some small Seattle businesses, they would not be impacted by the state-wide wage hike — they're already on the path to a higher wage.

Let's say you're a hypothetical Seattle business owner who was opposed to the city's minimum wage hike because you believe the higher labor cost would make it hard to compete with businesses outside the Seattle city limits. Why would you spend a lot of

After all, it would mean the businesses you were competing with outside the city limits would be legally required to pay wages closer to what you're paying your workers.

In 2013, over $277,000 of the money donated to oppose the SeaTac wage hike came from individuals, businesses or political action committees located in Seattle, with the bulk coming from Alaska Airlines. But so far this year, not a single one of the seven donations to the No on 1433 is from Seattle.

The Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce and its Civic Alliance for the Sound Economy PAC, for example, donated a total of $5,500 to try to stop the SeaTac Initiative. They aren't planning on donating anything to try to stop this one, saying they prefer to focus on "policy at the local level."

Ollada says some Seattle businesses have similar focuses.

"It doesn't affect them personally," she says. "While they need to come together as a coalition, in Seattle, they're worried about how they're keeping their doors open. They're not as concerned about how other people are operating."

Stephanie McManus, spokeswoman for the Washington Hospitality Association — a group that, as the Washington Restaurant Association, has donated $25,000 to the efforts fighting the minimum wage hike— says she heard plenty of complaints statewide about how the wage hike will be difficult to handle, but few of them have come from Seattle.

"I think we probably do hear less from people in Seattle," McManus says. "I think that’s because they’re already accepting that’s what’s happening for their businesses."

"We’ve been fighting this battle for a really long time," McManus says.

Meanwhile, only about 13 percent of the money raised for Initiative 1433 come from places that would see their minimum wage hiked as a result of the initiative.

A little over 20 percent of the money comes from out of state, while two-thirds comes from Seattle, where the Raise Up Washington campaign is headquartered. The majority of the 558,000 in in-kind contributions also come from organizations headquartered in Seattle.

Most of that Seattle funding comes from one wealthy donor, Nick Hanauer, and from unions like the AFL-CIO,

"Unions represent hundreds of thousands of workers across their state," says Sorensen. "The vast majorities of their members are outside of

Meanwhile, the Seattle Times editorial board, after years of penning editorials warning against minimum wage hikes, changed its tune last week, saying "for the sake of hundreds of thousands of low-wage workers, Washington should give it a try."

Seattle was "gambling with its economy" when it raised to $15 an hour, the Seattle Times editorial board wrote in 2014. But the Washington state proposal to raise the statewide wage to $13.50? "Bold experiment."

And that gets to another possibility.

Seattle hasn't yet reached $15 an hour. Currently, the city's minimum wage ranges from $10.50 to $13 an hour, depending on the size of the business and whether it pays for medical benefits. But so far, the change hasn't destroyed Seattle's economy. In fact, it's still booming.

Sen. Michael Baumgartner, who believes the initiative would be very tough on small businesses in border communities like Spokane, suggests that some minimum wage critics oversold the consequences of prior hikes, which hurt their argument in the long run.

“Sometimes the opponents of the minimum wage increases have a little bit of a ‘boy who cries wolf’ aspect,” Baumgartner acknowledges. In other words, they paint apocalyptic visions of mass small-business failures, when, in reality, the impacts of minimum wage hikes are smaller and more subtle.

That was the finding of the University of Washington study of Seattle's minimum wage earlier this year: The initial hike to $11 an hour slightly improved wages for the lowest-paid

"When we talk about the impact of the initiative, we talk to Seattle workers," Sorensen says. "They talk to us about what that experience has been and the difference that making more money and taking more money home in their life [makes]."

The results in Spokane, which has a much lower cost-of-living than Seattle, might be different. According to the rough estimate from Sperling's cost-of-living calculator, to maintain the same standard of living, a worker making the current minimum wage of $9.47 an hour in Spokane would have to be making about $16 an hour in Seattle. Spokane, according to this year's estimate by SmartAsset, had the third-highest minimum wage in the country, when you adjust for local cost-of-living levels.

On the other hand, no matter where you are, surviving on minimum wage is rough. Sorensen points to a study showing that, even in Spokane, it's extremely difficult to afford rent on a minimum wage salary.

He stresses that polling shows the initiative is supported throughout the state, not just Seattle.

"We're passing by 60 percent in Spokane," he says.

Tags: Minimum Wage , News , Image