Say what you will about America’s homebred religion, but one thing is undeniable: The Mormon church is moving into mainstream pop culture in a way not seen before.

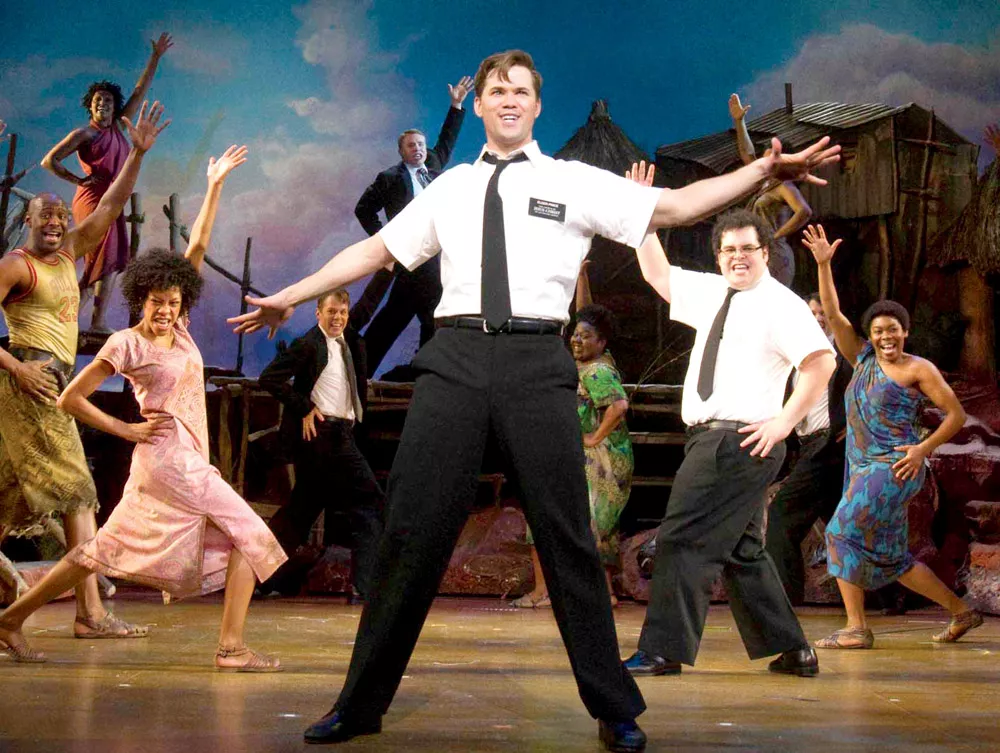

There’s Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman, distant Mormon cousins both running as Republicans for president. There’s The Book of Mormon, the Broadway musical about Mormon missionaries by South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker that swept the Tonys last month.

The Twilight vampire novels — written by Stephenie Meyer, a Mormon — were the biggest book-movie tsunami to crash into American culture since Harry Potter. Political leaders Glenn Beck and Harry Reid are Mormon. So are actors Amy Adams and Jon Heder.

While many Americans are only now learning about the church and some of its notable members, Mormons have long been a part of the Inland Northwest, with as many as 20,000 now living in the region.

Here we’ve profiled a handful of local Mormons as they consider faith, politics and the church’s leap into American consciousness.

Religion, Door-To-Door

Mormon missionaries — easily identified by their white shirts, ties and ID tags — are being stopped on the streets of New York City for autographs and photos, says Gordon Conger, a spokesman for the Mormon church in Washington state. Copies of the Book of Mormon are also being taken from New York hotels at far greater rates.

Why? The Book of Mormon — the raunchy, critically acclaimed musical — is at least partly responsible. Lampooning organized religion, the musical centers on two naive Mormon missionaries in Uganda who try to bring God to the locals, who are more concerned with famine and AIDS.

“That’s a bit amusing to me,” Conger says, “because something that is totally irreverent… itself is having a positive effect.

“It all begins with curiosity, and this current convergence has built a lot of curiosity.”

But that hasn’t exactly been the experience of two missionaries in Spokane.

With a knock, the door of a South Hill house swings open.

Standing there are two clean-shaven 20-year-old men, with white shirts, ties, beaming smiles and two black embossed nametags: “Elder Farnsworth” and “Elder Sigler.”

New Mexico native Todd Farnsworth — who looks slightly like Twilight’s Taylor Lautner — does most of the talking, while Grady Sigler occasionally interjects.

“Sorry, this is a bad time,” the woman inside says. “And I’m not really interested. It’s against my religion.”

“What do you believe?” Farnsworth asks. “Hindu,” she says. “Thanks, though. Have a good day.”

So it’s onto the next door, to ask the homeowners to hear about their faith, if they need any yard work done, if they have any neighbors who recently moved in or had a baby. People in the middle of big life changes tend to be more interested in religion, the missionaries say.

In all, Farnsworth estimates that he has knocked on more than 14,000 doors during the 19 months he’s served. He and Sigler, like many devout Mormon men between 19 and 25, left their families for an intense, two-year mission to convert unbelievers.

Launched from the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah, 52,000 young Mormon missionaries knock on doors around the world each year. Through birthrates and conversion, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been one of the fastest-growing religions, adding about a million new followers worldwide every three years.

Some answering the door have asked Farnsworth and Sigler about the musical, but it’s still a hard sell.

“We get rejected probably 30 or 40 times a day,” Farnsworth says. He’s been cursed at, yelled at, greeted with the barrels of guns. Just last Wednesday, a woman spit on him.

Amid the thousands of polite and not-so-polite dismissals, he’s helped convert 20 people. He forgets the rejections, but remembers the successes.

“There are trials for a reason,” Farnsworth says. “They help you learn and grow and understand. … The purpose of the mission is to learn who we are.”

Public Life

Ozzie Knezovich is no stranger to headlines. As Spokane County’s sheriff, he’s had to deal with questions of shrinking budgets, layoffs, police brutality and jail building. On the job, he’s a stoic law enforcer, equipped with a handgun and badge. But as a private individual, he is a devoted Mormon.

“My faith is something that is very close to me,” Knezovich says. “Your core values are what you bring to the table everyday.

The core values that I was raised with are to tell the truth, do the right thing, work hard and treat people with respect. And that’s what I try to do.”

Knezovich is one of the most prominent local Mormons in elected office, but he certainly isn’t the only one. Both of Idaho’s U.S. House representatives, Raul Labrador and Mike Simpson, are Mormon. So is one of the state’s U.S. senators, Mike Crapo. Keith Allred, a Democrat and a Mormon, ran against Idaho Gov. Butch Otter last year, but lost.

Unlike some politicians, Knezovich says he doesn’t like to discuss religion in the context of politics, but it’s not because he worries his Mormon faith will damage his prospects of re-election.

“I like to think that we’re in the 21st century and that we’re beyond that,” he says.

He may be right. In a June Gallup poll, three-quarters of Americans said they would vote for a Mormon for president. Only 22 percent said they wouldn’t, even if the candidate was their party’s nominee; that number hasn’t changed since 1967.

But not all of the news is good for Mormons. In the same poll, the Mormon faith ranks worse than the Catholic, Baptist and Jewish faiths. The only belief system that is rejected by more of those polled is atheism, with 49 percent saying they would never vote for a non-believer.

Perhaps all it would take is a Mormon president, as was the case with Catholics and John F. Kennedy. In 1959, 25 percent of Americans said they’d never vote for a Catholic. After Kennedy, a Catholic, was elected in 1960, that number tumbled to 13 percent, near to where it is today.

Asked about the current Mormon candidates for presidents, Romney and Huntsman, Knezovich says he hasn’t paid close enough attention to their candidacies to have an opinion.

Knezovich can trace the Mormon line in his family to the 1850s, to the time when Mormons were “coming across the plains and into the Utah valley.” He hails from the Warden and Rasmussen families, two of the original Mormon pioneer families that made the journey West with Brigham Young.

In Wyoming, where Knezovich was born and raised, the Mormon stake his family belonged to had 4,200 members. When his parents split, he stayed with his father, who was Catholic, and attended three years of Catholic school.

It was hard. “Oh it was, especially when you’re a Mormon,” he says with a laugh.

By the time he was 18, he was far enough away from the religion he was born into that he didn’t complete a mission. As a young adult, he says, he began to question his faith.

“Every kid growing up, in the college years, goes through that, ‘Who am I? What am I doing?” he says. That changed as he grew older, and now he relies on his faith on a regular basis.

“There have been times during my career when my faith has really supported me,” he says. “I go to church every Sunday I’m not working. And I try not to work very many Sundays.”

And when it comes to the various roles he plays in life, Knezovich says he has no problem keeping things in perspective, in large part thanks to his faith.

“I don’t know if you can be a politician first, but maybe you can,” he says. “I’m first a father, a husband.”

A Mormon is Born

On the carpet of her Spokane apartment, Mariah Phillips kneels, crosses her arms and prays with three Mormon men guiding her through the theology. She’s preparing for July 30, when she’ll be baptized as a Latter-day Saint.

It will mark the end of a journey begun little more than a month ago, when she fled California with her infant son, looking for a fresh start in Spokane. Then came a knock on the door: missionaries Sigler and Farnsworth.

“They asked if they could give me a Book of Mormon,” Phillips says. She accepted. She’d always been religious — she says God and church helped her through her darkest times.

“I may be 19, but I’ve had a worse life than most 40-yearolds,” Phillips says. Her mother, she says, was murdered when she was an infant. By whom, she doesn’t know. She says things happened to her when she was a kid — things she doesn’t want in the paper.

At 14, a doctor told her she wouldn’t be able to have kids. She managed to have a child anyway — then discovered the father was cheating on her 10 days before her wedding.

Now that he was out of her life, she decided to raise her 10-month-old son, Chase, in the church. “Knowing some of the Mormon beliefs … it clicked,” she says. “That’s how I wanted my son raised.”

During the prayer, Chase babbles and squirms, clutching at toys in front of him. Phillips apologizes to the missionaries, and requests another copy of a pamphlet they gave her last week. Chase threw up on hers.

Last year, about 200 Spokane-area residents like Phillips were converted, according to church officials. This year, the number of converts is up 15 to 20 percent.

On a recent Sunday, Phillips stands at the church pulpit, asked to give her testimony — a recitation of things she knows to be true. It doesn’t take long, only about four minutes. She says she believes there was a reason God wanted her to move to Spokane, that — even though being a single mom was hard — she’s absolutely certain that, right now, she’s happy.

She’s crying. Many in the congregation are crying. “I’ve never been happier in my entire life,” Phillips says later. “It’s like someone is watching over me and my son.”

‘Broader Discussion’

Digging into his family history shows Brian Pitcher the many paths people take to reach the Mormon church. Pitcher can trace his own heritage to recent converts to the faith. He can also trace his family tree to people who joined the church during its nascent days — relatives who were killed in anti-Mormon attacks as Joseph Smith’s followers migrated from the Midwest to the Rocky Mountains.

Nowadays, Pitcher hears stories of Mormon missionaries getting asked for autographs on the street. And with Romney and Huntsman mounting soapboxes nationwide to promote their presidential candidacies, Pitcher says things have changed in the Mormon world.

“There has been a broader discussion among journalists, and among leaders, and in the public in general about who are the Mormons,” Pitcher says.

Pitcher serves as the chancellor of Washington State University-Spokane, and the president of the Spokane Washington Valley stake of the church.

Like Huntsman, Pitcher has spent time out in the world. Raised on a farm in Alberta, Canada, Pitcher left for France at 19 to proselytize overseas. That was a difficult experience, he says, because the missionaries ran up against the country’s long history of Roman Catholicism.

Pitcher recalls a time when he, along with his fellow missionaries, arrived in the town of Pau, and though tired from their journey, decided to spend a few hours going from house to house to talk to residents. It was then that Pitcher says he encountered a young family that was looking for answers.

“They were just like … sponges eager to soak up new lessons,” says Pitcher. “The lesson to me was when you believe in a truth and keep working at it with faith and prayerfully… our father in heaven will bring those who are seeking truth to find us.”

About 40 years later, Pitcher looks back on that as a victory of his time abroad. But he says new challenges are mounting for the church.

With divorce and unemployment rates skyrocketing, Pitcher says families are working harder to stay together and harmonious. His congregations now include more single men and women than when he was growing up, he says.

“That’s just a secular trend that is affecting church and society,” Pitcher says of the divorce rate.

Pitcher, 62, will retire from his post as stake president in about six years, he says, and it may be up to the next generation to deal with the challenges of a growing church.

As stake president, Pitcher is responsible for helping aspiring missionaries with their application process.

Through this process, he has become acquainted with today’s young people. He says he is impressed, and more importantly, hopeful.

“I think that young people today that we see in church are really high-quality,” Pitcher says. “They’re more mature, experienced and talented than I think my generation was.”

Temple Building

Last Sunday morning, 200 people streamed into the 9 am service at the Mormon church off of Highway 27 in south Spokane Valley.

Across the parking lot stands the area’s Mormon temple — district from a Mormon church, it’s a small, rectangular building topped with a golden statue of a trumpeting angel. Constructed little more than a decade ago, it’s further proof of the church’s growth. Indeed, before 1980 there were only 15 Mormon temples in the world. Now, there are 134.

Before this temple was built, church members had to drive to Seattle through the night to get married, East Stake President Greg Mott says.

“Two of my children were married at the Spokane Temple,” Mott says. “Not very many years ago, I would not have dreamed it was possible.”

But for all the Mormon buzz, the services themselves have remained traditional. Here, there’s no overhead projector, PowerPoint, choir or rock band. Just a simple podium up front and hymnals in the pews.

In one pew sits Timothy Maughan, a 43-year-old doctor, alongside his wife, Camille. Their 12-year-old daughter, Gretchen, holds the hymnal for her 6-year-old sister as they sing Hymn 244, “Come Along, Come Along.” This ritual hasn’t changed. The family sings:

“Obedience will spring from each heart with a bound, And brotherhood flourish the wide world around.”

Comments? Send them totheeditor@inlander.com.