Twisting his head forward and to the side, Aaron Johnson reaches back with his right hand, his still functioning hand, to point out a quarter-sized knot of purple scar tissue at the base of his skull, just behind his left ear.

"There's the exit wound," he says.

A .40-caliber bullet had struck Johnson just below his jaw, passing through his neck and out the back. The entry wound, another tinted pucker of flesh, lies hidden beneath a patch of wiry beard.

A third scar runs the length of Johnson's left forearm where one bullet smashed the bone. Surgeons put in a plate, but his left hand remains frozen in a loose fist. A couple of more bullets — of nine total shots fired — ripped through his liver and lung, coming to rest near his spine.

At a lunch table in the psychiatric unit of Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, he sits stiff with the forced posture of a plastic back brace. Between bites of double-cheeseburger, Johnson describes himself as a "good guy," beset on all sides by judicial corruption, government conspiracy and demonic forces.

Johnson, 30, has spent most of his adult life in and out of both corrections and mental health facilities. His family knows him as a sweet, loving kid who struggled to focus and dropped out of high school. At 21, he went to prison on a forgery charge, and psychiatrists diagnosed him with schizophrenia. He's gone from jail cells to group homes to the streets, on and off meds, searching for some sense of stability.

"I've been trying to get on my feet," he says.

His private struggles made headlines this past Jan. 16, when his erratic behavior brought four Spokane police officers to a dark alley behind the Truth Ministries shelter on East Sprague. In a tense moment, the armed authority of law enforcement confronted the unpredictability of mental illness. And in an all-too-common result, it ended in violence.

Investigators say SPD officers surrounded Johnson. A knife blade flashed as officers closed in, and they yelled commands to drop the weapon. A repetitive clicking rattled off as a Taser fired. Then, they say, Johnson charged toward a nearby officer.

"They just opened fire," Johnson says.

While research studies have shown again and again that people with mental health issues do not pose a higher risk of violent behavior, serious symptoms can sometimes cause people to become disoriented, act in bizarre ways or cause disturbances in public that can attract the attention of law enforcement. With about one in 17 people suffering from a serious mental illness, police have increasingly become the first responders to mental health crises.

A 2014 research analysis examining how law enforcement interacts with the mentally ill found many police organizations across the country lack consistent training on diagnosing and engaging people in mental health crisis, and as a result officers can unnecessarily use excessive or deadly force against people in need of help.

"Serving as de facto psychiatric specialists, police officers often must assume roles held by nurses, social workers and case managers as the [principal] referral source to psychiatric emergency services," the analysis states. "For these reasons, it is crucial that officers are equipped with knowledge about various mental illnesses, and have the appropriate communication skills to safely intervene [with an] individual who is experiencing a psychiatric crisis."

In recent years, area law enforcement agencies have drawn intense public scrutiny over high-profile tragedies between officers and the mentally ill, most notably the in-custody death of Otto Zehm, a 36-year-old schizophrenic janitor badly beaten by Spokane police officers in 2006. A review of use-of-force records indicates a significant number of incidents still involve officers using force against people suffering from suicidal or mental health issues.

In 2013, Spokane police officers responded to a minimum of 1,100 incidents involving citizens with mental health issues, according to the city's police ombudsman. Most of those did not require any police action. But the ombudsman's analysis of Taser usage between 2010 and 2012 shows almost a third of those incidents — 23 out of 79 total Taser uses — involved signs of mental instability or suicidal intent.

As America's law enforcement agencies have worked to improve officer awareness on mental health issues, many have adopted "Crisis Intervention Team" training as the gold standard for partnering with mental health providers. The Spokane Police Department first introduced limited, voluntary training in 2004, but a 2012 settlement with the Zehm family mandated $200,000 to put every SPD officer through the 40-hour training course.

The final class graduated last Friday.

Julie Schaffer, an attorney with the legal nonprofit Center for Justice that represented the Zehm family, says the expanded training serves as a much-needed step toward improving awareness and safety for both local officers and the mentally ill. Police officials must foster a department that recognizes its obligations to protect people with mental illness and connect them to treatment.

"I think it is overdue," Schaffer says. "It's unfortunate that we've had to have so many incidents. ... There has to be a culture change at the department."

In a bright classroom at the Spokane Police Academy near Felts Field, SPD officers look up at a "jumper" pacing on a table top. Behind the man, thick blue mats have been set out to catch him if he leaps from the "bridge." The jumper, another SPD officer acting as a distraught middle-aged man, shuffles precariously atop the table. He swears at officers, waves his arms and rattles off a long list of complaints. He finally throws up his hands as he curses his life.

"I've had it," he tells the officers. "I'm done."

Jan Dobbs, chief operating officer for Frontier Behavioral Health, watches the scenario from a nearby seat. She has led CIT training efforts in Spokane since the start of the program more than a decade ago. Now working with SPD Sgt. Anthony Giannetto, Dobbs says the program has made an unprecedented push to train all SPD officers over the past year, putting the entire department through the weeklong regimen of lectures, demonstrations, role playing and guest speakers to instill new de-escalation and psychiatric diagnosis skills.

"Police officers learn in a certain way," she says. "They're very visual. They're very tactile. ... You have to reach them in a different way."

National law enforcement associations as well as mental health groups, like the National Alliance on Mental Illness, recognize CIT as an "evidence-based best practice" for engaging people with mental health issues. Police officials and researchers in Memphis, Tenn., first developed the CIT program in 1988, following the fatal officer-involved shooting of a mentally ill man. As many as 2,800 police agencies now train with what's known as the Memphis model. This includes dozens of departments in 12 counties across Washington and 13 counties in Idaho. (See "Regional Approaches" below.)

Some sessions, like the jumper exercise, focus on communication strategy and real-life scenarios. Dobbs says other sessions strive to put officers in the shoes of the mentally ill, building personal understanding and empathy. Officers train alongside local mental health providers and interact with people living with mental health disorders, listening to intimate panel discussions on their everyday challenges. They learn about the difficulty of juggling meds or hearing voices.

This particular afternoon is mostly dedicated to the role-playing exercises. After spending about five minutes talking with the jumper on the table, one trainee officer sees an opportunity and lunges for the man. Both trainee officers and the jumper go tumbling into the blue mats in a crashing clatter of toppled tables and muffled groans.

"Whoa," the instructor shouts, halting the scenario. "Don't snatch people off of bridges. It's too dangerous."

The instructor explains to the officers that he understands the instinct. Officers want to save lives. They want to pull people to safety. But with physics and weight and all the other unknowns, they could easily push someone accidentally or get pulled over themselves.

"Let's go back out and let's do this again," he says.

Just a day after the jumper scenario in the January CIT training session, Aaron Johnson, then 29, arrives at check-in for the Truth Ministries shelter. Recently released from the Spokane County Jail on a probation violation, he had spent four nights in the 50-bed shelter. Director Marty McKinney says Johnson became upset when staff try to check his backpack. Johnson says later he believed the shelter had given away his bed.

McKinney says cuts to mental health treatment services have brought more mentally ill through his doors. He says staff suspected Johnson might have an issue after he once signed in with a Russian name, claiming to work for the KGB. But on Jan. 16, Johnson crosses a line when he allegedly starts threatening staff with a 4x4 board.

"He was acting really paranoid," McKinney says, adding. "The police get a pretty hard time with all the shootings, but [in this case] I think they did exactly what they had to do, unfortunately."

Still carrying the board, Johnson ducks out the back of the building while shelter staff call 911. Shortly before 9 pm, several SPD officers converge on the alley behind Truth Ministries. Investigators say the officers find Johnson huddled under a blanket. But as they approach and identify themselves, he allegedly jumps out brandishing a folding knife.

"I didn't have a knife in my hand," Johnson argues later. He acknowledges he had a knife in his pocket, but denies ever displaying it.

McKinney says video cameras inside the shelter show Johnson acting erratically and waving the 4x4 board, but they never show him with a knife. The shelter did not have a camera covering the alley. SPD officers also have not yet started wearing body cameras to record encounters.

"Johnson looked very agitated, and tense while gripping the knife," officers observed in court records. "Johnson apparently had a strange look on his face, like a 'thousand yard stare.'"

Johnson remembers being surrounded by four officers, who the police department name as Officers Christopher Conrath, Michael Schneider and Holton Widhalm along with Sgt. Terry Preuninger. As Johnson moves close to one officer, Schneider reportedly fires his Taser.

Officers report Johnson stiffens up and goes tense, but he "fought through" and charges at officers. Two officers, Conrath and Widhalm, fire nine shots, striking Johnson several times.

Johnson says he remembers a short argument with officers, then with the shock of the Taser, he "started jumping everywhere." As they opened fire, he crumples to the asphalt, bleeding and disoriented. He says he can't remember anything else until he awoke in the hospital.

"They straight wanted to kill me," he says.

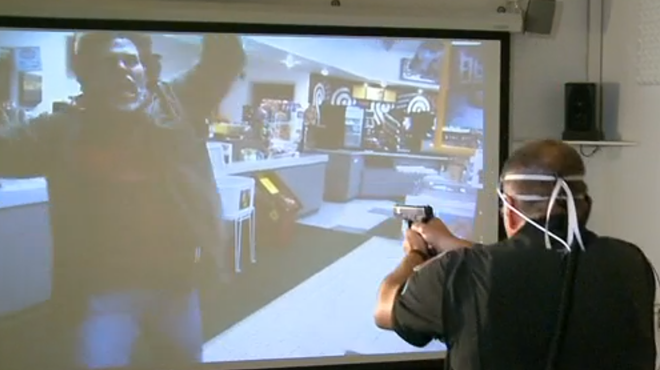

With the lights dimmed low, CIT trainee officers stand before a curved 180-degree interactive video screen. The sophisticated training system allows officers to go through virtual enforcement scenarios to test their awareness and reaction times. Officers can change the scenario outcomes by using verbal commands or several types of force, including firearms.

In this scenario, the officers follow a video officer into a home where they encounter the owner along with a wheelchair-bound man in a camo jacket. Within four seconds, the man in the jacket draws a weapon and kills the first officer as trainees return fire.

"This is going to look like Spokane police shoot disabled veteran in a wheelchair," the instructor says. "What I want everyone in the room to see is how fast this happens."

Dobbs, from Frontier Behavioral Health, watches from against the wall. She says she recognizes how quickly officers must react to subtle clues in behavior or appearance. She says she admires the high level of training officers get at the department. As they move through other scenarios, officers Taser a violent homeless man. They also resort to shooting an armed suicidal man heading into an office building. All of the scenarios have been recreated from real-life incidents.

"I don't know that there's a right answer," Dobbs says of the variety of officer responses. "There could be better answers."

Spokane Police Chief Frank Straub says he has always considered mental health training and community collaboration to be high priorities, developing a mental health steering committee with local treatment providers and researchers when he first arrived. He sees expanded CIT training as an important step forward in protecting officers and transforming the regional system.

"For the individual officer, the idea is to really put another tool on the officer's belt," he says. "We want to give officers the ability to engage people that are in crisis. ... It's a recognition that there's a whole bunch of things you can do other than just using force."

Department records show all of the officers at Truth Ministries had previously graduated from CIT training except Preuninger, who completed the class a month later. Straub acknowledges the limits of CIT training, explaining some people in crisis may be too dangerous for de-escalation attempts.

The best way to keep such people — and officers — out of harm's way, Straub says, is to support a robust local mental health system that can provide preventative treatment. A broader community approach can help stabilize people earlier and keep them from spinning out of control.

"By the time police arrive, they're maxed out in terms of crisis intervention," Straub says. "Then it becomes a very precarious situation as to whether the officers are going to be able to bring that person down. ... We can't look to the police as the solution to this problem. We're not."

Beyond officer training and education, advocates say the Crisis Intervention Team model must serve as a larger community infrastructure for partnering law enforcement with mental health facilities, hospitals, shelters and other stakeholders. Officers need to know local mental health professionals and get practical introductions to drop-off facilities or other treatment resources.

Dr. Randolph Dupont, a leading national consultant with the CIT Center at the University of Memphis, tells the Inlander the training program combines useful tactics with a new appreciation for the complexities of mental illness.

"Officers value the training," he says. "[They] usually have their hearts in the right place. ... It's good to have a lot of officers that have those skills."

Research studies by Dupont and others indicate CIT training not only protects vulnerable citizens, it can also reduce officer injuries, SWAT deployments, jail costs and use-of-force incidents. Mental health facilities may see more referrals for treatment services. The program can also increase diversions to treatment facilities instead of jails, which one study connected to improved psychiatric symptoms in those people three months later.

Dupont took only one issue with the Spokane approach to CIT. He says the Memphis model only trains volunteers, many of whom have a pre-existing interest or awareness of mental health issues that helps motivate them. Mandatory CIT training can breed resentment or devalue the lessons.

Ron Anderson, president of the Spokane chapter of NAMI, echoes some similar concerns about the mandatory program, but he notes Spokane's voluntary training sessions sometimes failed to get enough officers to sign up and were canceled. He remains encouraged by the department's commitment to expanding its mental health training. He says officers need to know about local resources and should understand what challenges people like his daughter may struggle with.

"Mental health ... is a huge factor in public safety and the welfare and well-being of our city," he says. "We need more than just 40-hour training for our police department, [but] it's a huge piece."

Schaffer, with Center for Justice, says the department should embrace the "social work" side of law enforcement and give additional recognition to officers who successfully avoid using force. That's the culture change that needs to guide officer recruitment, follow-up training goals and future community partnerships on diversion programs.

"That comes from the top," she says.

Sitting at their dining room table, Geri and Sharon Johnson sort through old family photos. They adopted Aaron when he was 11 weeks old. A few weeks later, they also adopted his older sister, Megan, bringing them both to live at their home in Clarkston, Wash. The Johnsons were aware of the birth mother's alcoholism and schizophrenia, but they fell for the sweet children.

"From the time that he was a baby, [Aaron] was all hugs and kisses," Sharon Johnson says. "You dropped him off at school, and he'd give you a kiss and a hug. He was just a real loving little guy."

But Aaron struggled to express himself as a teenager and quickly lost interest in sports or other activities, she says. He dropped out of school, later getting his GED. The family had just started looking into psychiatric care as he approached 18, but then he could no longer be forced into a treatment or medication program. He didn't receive any consistent treatment until prison.

Since the family moved to Spokane Valley, Sharon says, Aaron has bounced from jail to Eastern State Hospital to the streets, staying with them for short stretches. He can take care of himself while on medication, but he often refuses to take it. Sharon says she's used to calling around to hospitals and county lockups, trying to keep track of where he may be on any given day.

"All you can do for Aaron is pray for him," she says. "There are times when that's all you have."

"And when he's off the medication," Geri adds, "you never know when something's going to happen."

"That's right," she nods.

The Johnsons say Aaron can no longer live with them after a violent outburst last September, just days after Megan died at 31 of cirrhosis. Sharon says Aaron had been talking to himself when he came over and attacked her, striking her in the face and then turning on Geri. Aaron then fell to the floor and suffered a seizure while they scrambled to call 911.

When they heard about the Truth Ministries shooting, they went to Sacred Heart to check on him, but could not find any records regarding his location or condition. Sharon Johnson says they spent days trying to learn if he was OK. Investigators would not provide information and medical staff cited privacy restrictions. It took two weeks before they could even visit his bedside.

"That still haunts me, that I couldn't go see him," she says.

In the cold gray of downtown Spokane in late December, SPD officers look up at a man pacing the narrow railing on the Monroe Street Bridge. Authorities have closed the street, bringing the city's core to a standstill, hundreds of eyes fixed on a solitary figure in bright blue, perched on a strip of concrete more than 75 feet above the thunderous Spokane River.

The 28-year-old man had taken to the railing at about 2 pm on a Wednesday. He strips off his jacket as he crisscrosses the railing. He waves his arms and kicks his feet, shaking out his legs, balancing on one, shouting and stamping. Then he leans back, arching out over the abyss below.

"He's flailing like one of those meth-heads," one bystander mutters.

Officer Davida Zinkgraf, the first to arrive, reports she could hear the man talking to himself in a loud voice. He speaks of satellites watching him and TV voices sounding in his head. He rambles about sex and death. He tells officers he wants to go to "heaven."

"At one point, he began clapping his hands," Zinkgraf writes. "[He] would then talk very quietly to himself, and it appeared to me he was preparing himself to jump into the river below him."

Straub, who soon responds to the scene, says officers took care to calm the situation. They turn off flashing lights and give the man room to vent. They offer to operate on his terms when possible. They bring in negotiators as well as mental health professionals.

"This is a very stressful thing," Straub says.

Such standoffs can easily turn tragic. In 2007, SPD officers attempted to Taser 28-year-old Joshua Levy as he stood near the railing of the same bridge. The Taser missed, and he leapt to his death.

And in February, Spokane County sheriff's deputies shot and killed Jedadiah Zillmer near the Spokane Valley Mall. The 23-year-old former Army soldier reportedly armed himself with multiple weapons and forced a confrontation with authorities to commit "suicide by cop."

"The intersection of law enforcement and mental health is a very dicey place," Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich says, adding, "You are at the mercy of the person that you're dealing with. If they're bound and determined to die that night ... there's only so much you can do."

After nearly 90 minutes of delicate negotiation on the bridge, Zinkgraf and others persuade the man to get checked out at Sacred Heart. He fights back tears as he struggles with the decision, she reports, but eventually he sits down on the railing and then slowly scoots off to the sidewalk.

"Yes!" someone shouts as onlookers sigh with relief.

Zinkgraf escorts the man down the bridge to a patrol car where he is allowed to smoke a cigarette. Then an ambulance crew moves in to check on him.

"He didn't get taken to jail," Straub says. "He got taken to treatment."

In the coming years, Straub says, the Spokane Police Department will continue to expand mental health training and outreach efforts. He says he's impressed with programs at the Los Angeles Police Department and the Portland Police Bureau in Oregon. Those programs involve multiple levels of advanced CIT training and proactive mental health units that team up with psychiatric specialists to visit high-risk individuals and monitor their ongoing treatment. (See "Alternative Programs" below.)

"That's a direction we'd like to go," Straub says. "My goal is to continuously ramp this up, continuously go out there and find out what the best practices are that are available."

With the entire department now trained, local advocates look forward to seeing how the program moves forward and whether uses of force against the mentally ill will start to decrease. Will they see the cultural change many have called for? Can local mental health treatment shift from crisis response to preventative care?

Since the Truth Ministries shooting, Aaron Johnson has volunteered for a short-term commitment in the Adult Psychiatric Unit at Sacred Heart. His parents don't know what his future holds. They say they don't know the long-term implications of his injuries. They don't know what charges he may face. They don't know where he might find a stable home.

It's all in "limbo" right now. They're desperate for some treatment program or housing option that could give Aaron an opportunity to get his life under control.

But for now...

"He has no chance," Sharon says, " ... if something doesn't get done."

The Johnsons, like many others, believe it will take a larger community effort to develop a mental health system that can provide a place for their son, that can keep the mentally ill out of police crosshairs and offer the help people need before they're teetering on the brink.

"This will happen again, something like this," she says. "Somebody else is going to get hurt or killed." ♦

Regional Approaches

In Idaho, Crisis Intervention Team training runs through regional programs in which multiple jurisdictions send officers through joint training sessions. Ann Wimberley, a NAMI advocate and Region 1 coordinator for the state's five northern counties, says Bonner County has hosted regional training annually since 2009.

Wimberley says North Idaho agencies utilize the Memphis model with an emphasis on practical "street" skills that officers can use on the job. In addition to the basic 40-hour course, they have also since introduced advanced training on "excited delirium" and youth mental health.

"We have had a lot of support for this program," she says.

Many North Idaho mental health agencies also hold "services fairs," she says, to introduce officers to local treatment facilities, staff and resources. State grants have helped fund the training and overtime costs in recent years.

Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich says training overtime costs have become a significant limitation on the number of deputies he can send through the CIT course. He would like to see an easier, hybrid mental health training program that deputies could take online, or during shorter, routine training periods.

"We need to start thinking outside the box," he says. "We have to find a better way. ... I think the skills are important."

Knezovich says he would also support integrating CIT training into the Basic Law Enforcement Academy at the state level, so all officers graduate with the training. Some advocates support that idea, but others argue that state academy training would not provide officers with an introduction to local mental health agencies or resources that make up a key part of the program.

Alternative Programs

Following a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice regarding use of excessive force against the mentally ill, the Portland (Ore.) Police Bureau last year established a central Behavioral Health Unit to expand training and proactive outreach regarding citizens with mental health issues. The unit maintains 50 officers with "Enhanced" Crisis Intervention Team training, which includes advanced training on mental health disorders and response techniques.

The bureau also created a three-car Mobile Crisis Unit, in which officers and civilian mental health professionals make proactive visits with repeat or high-risk clients to monitor treatment and services.

Just this month, the Seattle Police Department, following a DOJ consent decree, introduced a new policy mandating that CIT trained officers must respond to any scene involving a suspected person with mental health issues. Officers must also default to de-escalation if they can safely do so. The department also created a new Crisis Response Team to provide follow-up services for people.

The Los Angeles Police Department has long paired mental health professionals with officers to conduct proactive outreach efforts. The Systemwide Mental Assessment Response Team (SMART) works to link people with local services. In 2005, the LAPD added a Case Assessment and Management Program to identify and track high-demand people to provide routine monitoring and treatment stabilization.

Both of those programs operate under a central Mental Evaluation Unit, which can provide triage phone consultations to officers in the field or access medical histories on specific individuals.

The New York Police Department provides advanced mental health training to members of its tactical Emergency Service Unit, which can provide "psychological service technicians" to de-escalate confrontations. In recent months, mental health advocates have called for the NYPD to adopt the CIT training model to provide additional training to officers throughout the department.