As the body of the city's most famous pioneer lay silently at the Masonic Temple in 1921, the remaining old-timers and the next generation of city-shapers paid respects to the man known as the father of Spokane.

"With the passing of James Glover, the truest pioneer I ever knew is gone," said Joe Daniel, who moved to Spokane before its boom era. "He was a power and a force back in those early days, and he was a friend to everyone who ever knew him."

"He was a man of honor, strictly square in his business transactions and more loyal to his friends than any other man I ever knew," added Edward Pittwood, the city's first dentist.

"He was generous to a fault, and when he had much, he shared liberally with all," said W.C. Gray, who owned Spokane's first hotel. "He thought always of the other person, and had a helping hand always ready to extend. A truly great man has gone with the passing of Jim Glover."

More than 90 years later, in the final minutes of a committee meeting this past April, members of Spokane City Council decided against putting Glover's name on the new plaza beside City Hall. The stone with Glover's name had already been engraved for a dedication the following week, but questions had come up about whether the "Father of Spokane" deserved the honor.

"I found out things about James Glover I'm quite frankly not comfortable with," City Council President Ben Stuckart said. "He divorced his wife; she's buried out at Eastern State Hospital in an unmarked grave. This guy had some sketchy stuff going on in his past. It's not a joke. ... Is that somebody we want to honor as a city?"

Others around the table agreed it would be better to open the plaza without a name and involve the community in selecting a new one. The next Friday, the renovated Huntington Park and plaza opened to the public with live music, speeches and a new stone without Glover's name on it.

James Nettle Glover was by no means the first person to live in this place, nor was he the first white man to recognize the value of the falls. But he was the first white settler to envision a grand city around the falls and then spend his life making it happen. In his old age, the city boosters proudly said he was the only settler in America who lived to see his land claim turn into a city of 130,000 in less than four decades.

Scrub Glover from the story of Spokane, and the city as we know it ceases to exist. He once owned all the land in Spokane's downtown core, and he spent months in Olympia wooing legislators to establish the county's boundaries. He laid out the downtown streets and gave them their names: Sprague for General J.W. Sprague, the railroad superintendent he dealt with most often; Howard for General Oliver O. Howard, who stopped by while leading troops against the Nez Perce; Stevens for the governor of the territory; Post for local mill owner Frederick Post; and the rest for the presidents.

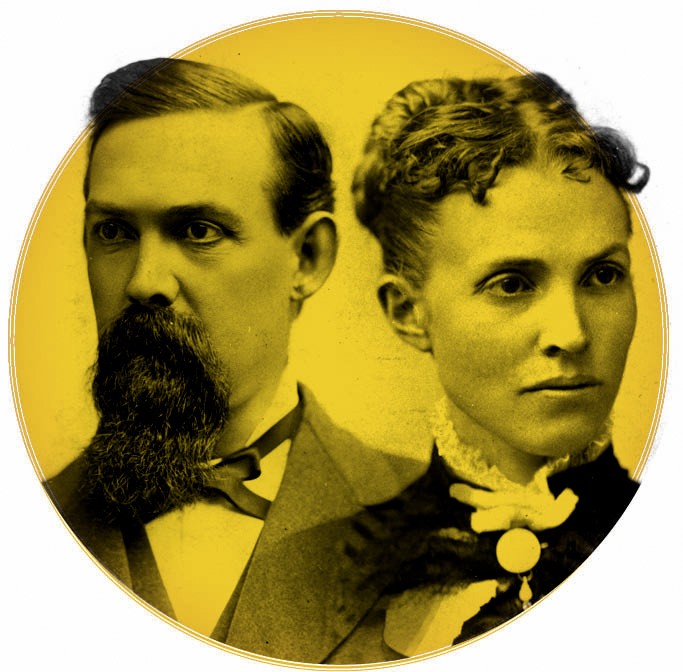

Other settlers and business partners came and left, and the only other white person to arrive in Spokane so early and stay long enough to be buried was Glover's wife, Susan Tabitha Crump. But she is notably absent in memories of Spokane's early days, an erasure more deliberate than the neglectful omission of many women at the time. Spokane's first Mrs. Glover was deliberately snipped out of history — out of spite, embarrassment and ignorance — many years before she was even dead.

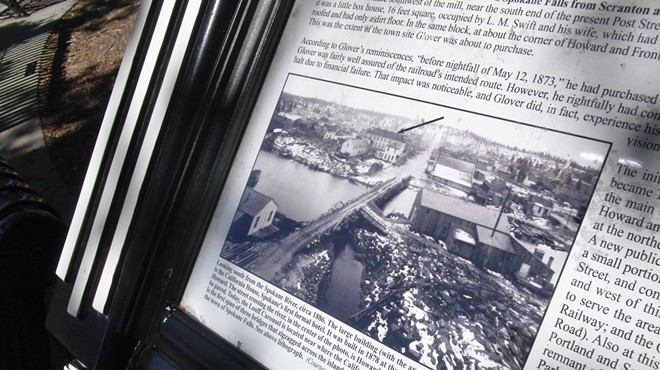

In his own telling, Glover arrived in Spokane Falls on a beautiful evening in May 1873. He'd traveled from Salem, Oregon, by rail, river and saddle with a business partner, Jasper N. Matheny, and they arrived to find a handful of wooden structures among the grass and basalt. At that time the river ran unharnessed over the falls, turning to spray against rocks later blasted to make way for industry. Two settlers, J.J. Downing and Seth Scranton, had built a sawmill, and the visitors were directed to an unfinished log cabin to spend the night.

Glover fell asleep to the roar of the falls, and the next morning went to explore.

"I was enchanted — overwhelmed — with the beauty and grandeur of everything I saw," he recalled later. "It lay there just as nature had made it, with nothing to mar its virgin glory. I determined that I would possess it."

By the end of that second day, Glover had worked out a deal to buy the land claim that encompassed all of the falls.

At 36, Glover was taller than most men and assessed the world with intense, blue eyes. Later in life he walked around town as a neatly dressed elder statesman, clean-shaven with a silk top hat and gold-topped cane, but he first came to Spokane with dark hair and a beard, skin darkened by the sun and dust. He returned to Spokane a few months later, in August of 1873, with his 30-year-old wife, a slim woman with high cheekbones. In portraits, her downturned mouth and pulled-back hair give her the appearance of someone strained against an invisible wind. During her lifetime, she was described as having a look of melancholy in her eyes.

Both Glovers had come from Missouri on the Oregon Trail as children. James Glover was 12 and the trip took six months and one day; Susan's family came earlier, when she was 3, and they traveled part of the way with the ill-fated Donner-Reed Party on a grueling nine-month journey.

Glover had worked an assortment of enterprises as a young man — a fruit stand in California, mining in North Idaho, a ferry business in Salem — and said he was drawn to the Spokane area because "Oregon was becoming pretty well filled up by that time."

The land wasn't poised for immediate success. Marcia Downing, one of the few settlers living there when Glover arrived, remembered the stony, unyielding ground many years later: "You couldn't put the end of your little finger down without bruising it."

Glover and his business partners improved the sawmill, but there was no demand for lumber. They opened the first store, but their only customers were the Spokane and Coeur d'Alene Indians who came to trade. Only four families lived in Spokane Falls when it hosted a centennial Fourth of July celebration in 1876 that drew visitors from miles around.

One of Glover's favorite stories to tell about the early days was from the summer of 1877, when fighting between settlers and the Nez Perce put the whole region on edge. Spokane Falls had barely grown in the four years since the Glovers arrived, and news of nearby violence made them aware just how quickly their small settlement could cease to exist.

One day a Nez Perce group set up on the edge of town and drummed through the night for two weeks. Glover watched them from the front of his store as the days passed and became more tense, and finally he called a meeting with some of the older Spokane Indian leaders. It had been less than 20 years since Col. George Wright had come through and slaughtered hundreds of the local tribes' horses, and this was still a painful memory. He asked the men at the meeting if they recalled this, and told them to make the Nez Perce men leave by noon: "I am in close touch with the soldiers — the boys with the brass buttons — and if they aren't gone by noon, I will tell the soldiers to come."

The next day, entirely by chance, an infantry regiment marched into town.

Glover, pleased on multiple counts, lobbied for the soldiers to stay. The military decided to build Fort Coeur d'Alene, later called Fort Sherman, and the added protection drew more settlers to the area.

Around the same time, work resumed on the Northern Pacific Railway, which had been slowed by financial troubles but was routed to come through near Spokane Falls. The city soon had its first school, first hotel and first newspaper, the Spokan Times. (The spelling of Spokane was debated, and publisher Francis H. Cook felt strongly that the "e" would lead people to mispronounce the city's name.) The first train pulled into town from the west in 1881, and word got out soon that gold and silver had been found in the mountains of North Idaho. After a slow beginning, Spokane Falls became a boom town.

For two years during this time, a 14-year-old niece, Lovenia, came from Salem to keep her aunt company while Glover was frequently away on business. The Glovers doted on Lovenia, and the letters she wrote back home are the only record of life in their household. She once saw her uncle turn down the covers and spank her aunt for failing to get out of bed in the morning, and she noted that her uncle did all the hiring of household help, which was unusual at a time when that was typically the wife's dominion.

But contrary to what was said later, Lovenia's letters prove the Glovers did share joyful times — the family exchanging gifts at Christmas, Susan playing organ for a choir practice, the Glovers dancing at a Masonic Lodge dedication in 1884. "You should have seen Uncle and Aunty get around," she wrote. "They were as light on their feet as any of the young folk."

Shortly before the Great Fire in August 1889, the Glovers moved into their grand mansion on Eighth Avenue, the first designed by Kirtland Cutter. Their time in the home was brief and troubled. In August of 1891, two years after they moved in, Glover had his attorney draw up "Articles of Separation," a less formal alternative to divorce. The four-page document declared that they would live apart, that all property belonged solely to James Glover, and that he would provide his wife with a carriage, a house in Oregon and $100 a month for the rest of her life. Susan departed for Salem almost immediately.

The following January, Glover filed for divorce. His complaint called the marriage "unfortunate in every respect" and accused his wife of being "wholly impotent, barren and incapable of reproduction." It continues: "This incongeniality which existed between the parties was so extreme that it rendered cohabitation and social intercourse between them repulsive, beyond endurance on the part of either, and in fact impossible."

In April, Glover added a paragraph claiming "cruel treatment," a way to expedite the legal process. His wife's failure to respond was considered by the court an admission of guilt, and a judge approved the divorce on March 31, 1892. The man remembered at his funeral for his kindness and loyalty extended no generosity to his wife of nearly 24 years.

Two days later, Glover married Esther Emily Leslie, a 33-year-old woman from Maine who worked at an insurance office. With doughy features and small, dark eyes, the second Mrs. Glover was neither a trophy wife nor a vivacious socialite. When she died alone a few years after her husband, her obituary listed no civic affiliations. But their marriage must have been a more tolerable one, and the niece who grew up next door remembered "Uncle Jimmie and Aunt Ett" with admiration and fondness.

At the time he remarried, Glover was a millionaire with the finest home in the city. Within a year, the United States fell into the Panic of 1893, the worst economic depression it had yet endured. Glover's entire real estate and banking fortune evaporated when the First National Bank failed in July, and he and his new wife were forced to move out of the mansion.

In an interview decades later, on the occasion of his 78th birthday, he recalled that time:

"When everything seemed going from us in the early '90s I saw some of my best friends going to the wall, men who were losing the accumulations of a lifetime, men who were broken with sorrow, and at that time I forbade my family to mention hard times and financial troubles at our home. It was one of the ways I had of sustaining the ordeal."

All that was left for the first Mrs. Glover fell apart on July 1, 1899. She had returned to Spokane from Oregon just a few weeks after the divorce was finalized, and she spent the next seven years moving from one downtown apartment to another. She decided to buy a house at 316 S. Ash St., which is now a parking lot near the Grocery Outlet store on the western edge of downtown, and moved her belongings there on the first of the month.

She came home that evening to find her piano in the street. All her possessions were outside, as if the house itself had spat them out. The hotel proprietor who sold the house said he'd never received payment from Mrs. Glover and moved on to another buyer. When he heard she'd moved furniture in, he and another man went to remove it.

Susan wandered down the block to the home of the McCreas, where she sat on the front steps, inconsolable, until they called the police. The Spokesman-Review reported: "Officer Beals found Mrs. Glover sitting on the steps. He tried to induce her to go home, offering to accompany her. She refused. Then the officer said he would send for a carriage and have some one in citizen's clothes go home with her. She violently replied that she did not want to go home, or anywhere, and that she would allow no one to lay a hand on her. When the patrol wagon arrived, Mrs. Glover refused to enter it. The officers lifted her bodily into the patrol. The crazed woman was placed in a cell in the women's department of the county jail."

A hearing was held, at which her former husband and other witnesses testified against her. Physicians filled out a form assessing her condition:

Is there suicidal, homicidal or incendiary disposition? No

Is there a disposition to injure others? No

Is this the first attack? Yes

In what way is the accused dangerous to be at large? unable to take care of her self

The news that she had been declared insane and committed to the asylum at Medical Lake warranted a single sentence in the Chronicle on July 4, 1899, between items about a young lady's sight-seeing trip to Lake Coeur d'Alene and two sisters' departure for a summer on the coast. The Spokesman-Review noted that "the woman has given the sheriff's deputies considerable trouble since her incarceration Sunday."

She never told the story, so we don't know what Susan Glover felt when she first laid eyes on the falls. No one made speeches in her honor or interviewed her about Spokane's early days. We don't know whether she agreed that life in the mansion on Eighth Avenue was "impossible," or at what point she stopped fighting the officials tasked with delivering her to the mental hospital.

At the time she was committed, Eastern State Hospital was called the Eastern Washington Hospital for the Insane, and it was meant to be a self-sufficient community with a dairy, bakery, smokehouse and pleasant grounds overlooking Medical Lake. The standard of care had moved from prison-like restraints, the hospital superintendent said in 1900, to modern methods of "kindness, tact, amusements, exercise, rest of the mind and body, and the proper administration of medicine where the mental or physical health require it."

But there was no treatment for "melancholia" or other mental illnesses, and no expectation that patients would get better. People with all manner of problems — depression, schizophrenia, learning disabilities, alcoholism, erratic behavior — were put into the custody of the mental asylum with the intention that they remain apart from society. In those early decades, the vast majority of patients arrived at Eastern State Hospital on a court order, and few ever left.

Susan gets no mention in most histories of Spokane, but her name is recorded in a handful of written memories of the city's earliest holidays and in a long family history written by one of Glover's nieces and filed with the Oregon Historical Society: "He married Susan Crump, an attractive and highly esteemed woman who from an illness fell into spells of despondency and eventually became completely deranged so that she had to be confined for many years before her death."

The daughter of the niece who once lived with the Glovers in early days of Spokane Falls recalled her mother mentioning an infant, and speculated in correspondence in the 1970s that the "illness" may have been a miscarriage or stillbirth.

Barbara Cochran, who researched the Glovers for historic portraits published posthumously as the book Seven Frontier Women, found anecdotes that suggest Susan Glover's health may have been a reason the Glovers left Salem in the first place. Existence for the quiet wife of the ambitious James Glover must have been desperately lonely in the early years, Cochran concluded, and then rapidly overwhelming as the city grew up around them.

With the perspective of many decades, the note Susan Glover wrote in an autograph book the Glovers gave their niece for Christmas in 1884 is a poignant plea:

"Long may you live

Happy may you be

And when you think of Spokan

Don't forget your Aunty."

Time both conceals and illuminates, and history is filled with great men judged more critically by later generations. When the names of these men grace street signs, parks and public buildings, communities continue to grapple with the best way to live with their history: Is removing a name an act of healing, or an act of forgetting?

After years of protests from parents, a school board in Florida voted this year to rename a high school named for Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general who was also an early leader in the Ku Klux Klan.

In Canada, a plan to install a plaque honoring Dr. Helen MacMurchy — a leading public health champion in the early 20th century — was scrapped at the last minute after it came to light that she was also a promoter of eugenics.

In New York, a street called Corbin Place became the topic of controversy in 2007 after a new book revealed that its namesake, 19th-century developer Austin Corbin, was an outspoken anti-Semite. To avoid a costly name change, the city council voted to rename the street for Margaret Corbin, a Revolutionary War heroine who took her husband's place in battle when he was killed.

Whatever Glover's faults, they do not fall on the scale of mass oppression and systematic injustice. He was not a killer or a slaveholder. There's no evidence he was more prejudiced than most white men of the time. The charges against him are far more intimate, and in that way more timeless — when a wealthy man leaves his mentally ill wife with nothing, there is no context of era or culture that can explain it.

Glover avoided serious scrutiny in his lifetime and died with his reputation intact. But in keeping his first wife out of sight — and out of history — Glover ended up jeopardizing the honored place he worked so purposefully to attain in Spokane's story of itself. Depending how harshly you judge his actions, it's either pitiful or justice that what he determined to forget has come to define his official legacy in the city he cared so much about.

Historian Tony Bamonte, who with his wife edited and further researched Cochran's book, considers Glover a domineering man who used his power to banish his wife when she became an inconvenience.

"His motive was to get rid of her," Bamonte says. "And not just to get rid of her, but to get her off the streets where people wouldn't know that she was having all these troubles and that he was leaving her penniless. And she didn't deserve that."

Throughout his life, Bamonte says, Glover told the story of Spokane in a way that embellished his efforts and marginalized the people who helped him along the way. He helped perpetuate the rumor — taught in local schools for many years — that the two settlers who preceded him, Scranton and Downing, were "horse thieves" in trouble with the law. (Scranton was accused, but found not guilty.) Glover downplayed the influence of others who promoted Spokane in the region, and suggested that business partners who abandoned the settlement in the early years left for lack of dedication and character, rather than practical concerns like money and medical care. Bamonte has no doubt that Glover pulled the necessary strings to make sure his first wife would not return to interfere with the image he was creating of himself.

Glover is a key player in Spokane history, Bamonte says, but it's important that the full story be remembered when his name comes up.

"I think the true story needs to come out," he says. "I think people need to know who he was and what he stood for, and how he manipulated things and how he sought his own recognition. ... He did some things that are not acceptable today, and there's a reason they're not acceptable."

Forty-eight years after he first arrived in Spokane, James Glover knew death was near. His legs no longer held him, and he refused to go to bed because he did not believe he would get up again. He'd had Kirtland Cutter design a modest, cottage-style home in West Central in 1909, and from there, day and night, he looked out from his chair on the tree-covered hills to the west of Spokane.

On Oct. 11, 1921, as Glover kept vigil over the city he founded, his first wife died at Eastern State Hospital just shy of 80. No family or birth year was listed on her death certificate, and she was buried in the hospital cemetery in a grave marked No. 746.

Five weeks later, on the morning of Nov. 18, Glover died quietly at his home. For a year and a half he had stayed in his chair, and his family finally convinced him to go to bed. He died two days later.

At the meeting after his death, the Spokane City Council passed a resolution honoring Glover's service to the city:

"He died in the fullness of years, honored by his fellow citizens, and leaves behind him in the city he helped to found a monument to perpetuate his name more enduring than modeled bronze or sculptured stone."

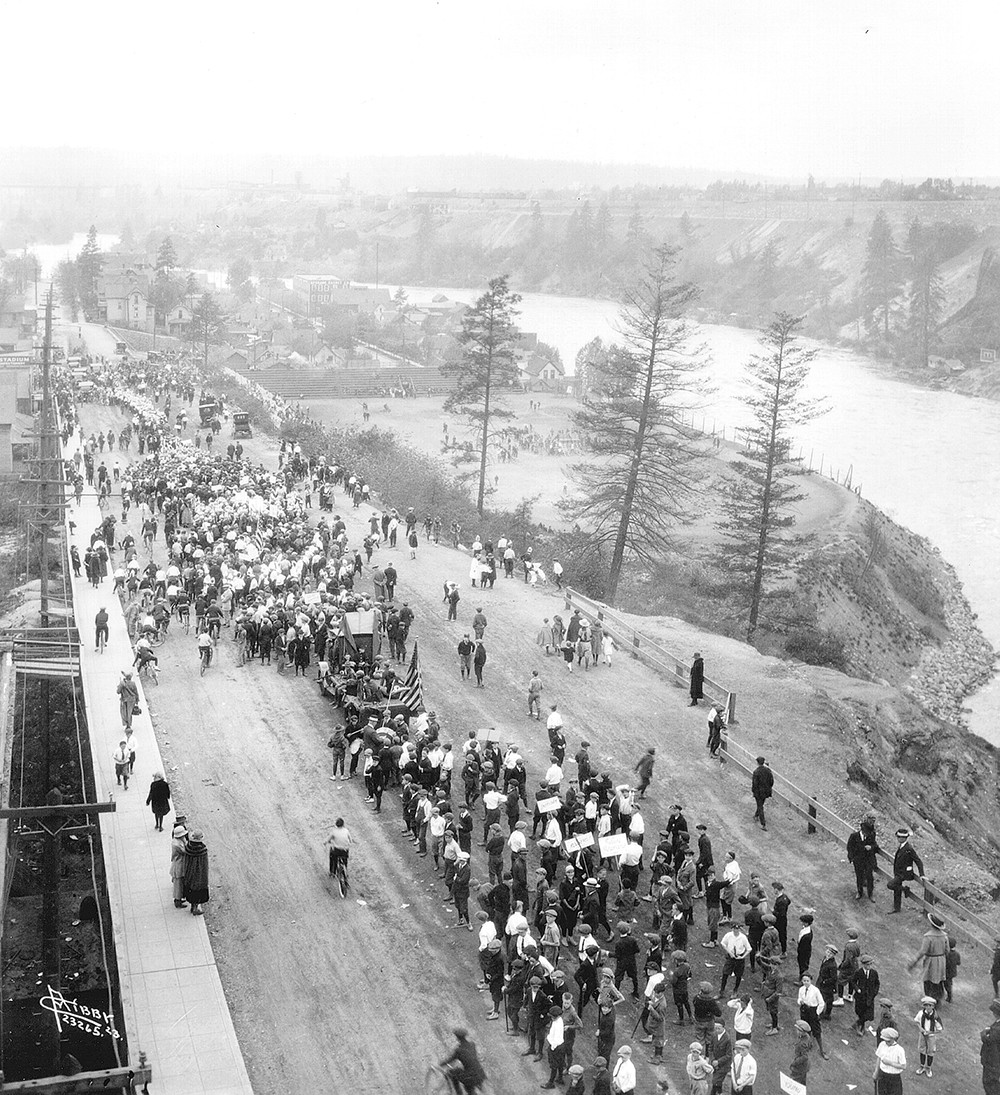

Glover Field, the ledge of grass beside the river in Peaceful Valley, was once lined with stands as the city's finest athletic stadium. Before that, it was a significant gathering place for the native people of Spokane, and the city has agreed to let the tribe rename the field in a way that recognizes the site's longer history.

It's not a deliberate ousting of Glover, and few people living in the city today even know the field was named for him. But once, on an autumn day nearly a century ago, a thousand people came to the field and cheered as a granite monument was unveiled to formally dedicate Glover Field as Glover himself looked on. The Chamber of Commerce and the Advertising Club — the new generation of city promoters — had made occasion to honor him at several events when it became clear that time was running out. But this was the greatest honor, and the Advertising Club announced plans to erect a full statue on the granite base so that Glover's figure could forever look east toward the falls. The Chronicle reported that the crowd chanted — "Glover, Glover, speech" — and the old man addressed the crowd with a tear in his eye: "Fellow citizens, I am always glad to meet with you."

The statue never materialized, and half a century later the base stood hidden in tangles of grass, its plaque gone and its granite edges chipped away. The Ad Club suggested it be moved to the grounds of Expo '74, now Riverfront Park, but parks officials deemed it inappropriately "tombstone-appearing."

Though most of the names Glover bestowed on Spokane's streets are still used today, he never named a street or any other landmark for himself. Glover Middle School was named for him before it opened in 1958, and will be his only civic presence once Glover Field is renamed.

In 1931, a decade after Glover's death, it was proposed that the recently rebuilt Grand Avenue be renamed Glover Way. No one liked the idea. "Absolutely not!" one man commented in the Chronicle. "Grand boulevard is the grandest name we could have for a street so fine. I'm not a bit strong for this idea of shaking off all the old names which have meant so much to Spokane." A smaller portion of Cliff Drive was briefly considered, and then the idea was dropped.

Today the Glover Field monument still exists in Peaceful Valley. The lowest tier of the concrete base is perched in the original place on the hillside along Main, covered in matted leaves and littered with punctured cans. The rest of the monument stands in a pale patch of grass beside the community center, a pillar of anonymous granite without any plaque or sign to identify the man it once honored. ♦

To involve the community in selecting a name for the new plaza by City Hall, the city asked for nominations that would "honor, depict and celebrate Spokane" and received several dozen submissions by the end of May.

Some nominations that garnered support include John Moyer Plaza, for the former state senator who opposed the Lincoln Street Bridge project that would have been built across the falls; Isamu L. Jordan Plaza, for the writer and musician who died last year; and names that describe the area's native people or landscape rather than a specific person.

Those nominations are now with the Plan Commission, which will discuss them at a meeting on Aug. 13 and pass on recommendations for a city council vote. The city plans to hold a naming dedication once the name is finalized.