"We came here because we have to save our lives," she says, sitting next to her husband. Now, they're tasting raw carrots from a paper boat, seated at a long table surrounded by posters about the Founding Fathers, with people chatting in four languages.

Refugees like Farwah Rubab and Syed Mubashar Abbas from Pakistan come here, to World Relief's headquarters in Spokane, for answers. Not only do they get help finding housing, schooling and jobs, but they can attend workshops on the essentials: banking, interacting with law enforcement and today, cooking healthy food.

"We like the bus, and we can take classes so we can improve our language," Rubab says. "[But] we want to be able for everything. We are helpless. We don't like this."

Though the much-covered influx of unaccompanied children at the southern border is 1,500 miles away from this classroom, the two are unavoidably linked by a pot of federal funding increasingly under stress.

Last month, the federal government halted funding to states for "refugee resettlement assistance" — the money that pays for these classes — because it needed that money to address needs at the border. In Spokane, World Relief, a nonprofit that helps resettle refugees, uses its $89,500 allotment to pay staff to help refugees apply for permanent residency and to organize these classes. The nonprofit Catholic Charities gets $35,500 from the contract to provide similar services. About $1 million in funding was cut for the current quarter.

While President Barack Obama requested $3.7 billion from Congress to address the border crisis, lawmakers went on recess late last week without approving any extra funding. It's unclear when and how fully the refugee funding might be restored. In the meantime, local organizations are in limbo as they decide whether they're able to piece together temporary funding or should start cutting staff and programs.

World Relief is not currently planning any layoffs, but Director Mark Kadel says if cuts continue, his organization would have to consider cutting staff associated with these programs. Catholic Charities is in a similar holding pattern.

"If this trend continues, we'll be faced with some decisions at World Relief," Kadel says. "Eventually, if there isn't a solution, there will be a trickle-down effect in the local economy."

While funding is a consistent challenge for service providers, cuts like this — where funding has already been promised and is then withheld mid-year — are rare.

"It is troubling," says Tom Medina, chief of Washington state's Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance, which distributes the federal money to local groups. "These are people we invited to the U.S. ... These people have been through the worst that life can give you and are on their feet. They get here and we pull services out from under them."

The influx of unaccompanied children at the U.S.-Mexico border didn't start this year, but it has reached unprecedented levels. According to the U.S. Border Patrol, more than 56,500 children were caught at the border between October 2013 and this June, up from just 15,700 in the 2011 fiscal year.

Most of the children are from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, where violence and poverty have driven families to take drastic measures to get children to the U.S. in hopes they'll be allowed to stay, according to a recent report from the Brookings Institute, a public policy think tank. Children from noncontiguous countries are treated differently than those from Mexico or Canada, who can be quickly deported. Instead, children from other countries are put under the care of the Department of Health and Human Services until family or foster care can be located. They're simultaneously put in "removal proceedings" within the Department of Justice, where they have to prove they're fleeing persecution or abuse and neglect by their parents to be allowed to stay.

Compared to states like Texas and New York, the Northwest will see relatively few of these children: In the first half of this year, 211 have come to relatives, family friends or foster parents in Washington, 50 to Oregon and eight to Idaho, according to the federal government. Still, their needs have tried resources at groups like Lutheran Community Services in Seattle, which matches unaccompanied immigrant and refugee children with foster homes. The group's sister organization in Spokane is now applying for grant funding to create a similar program, but is unsure whether the program could come to fruition in time to serve the immediate need, says Ashley Sorensen, a foster home licensor and therapist at Lutheran.

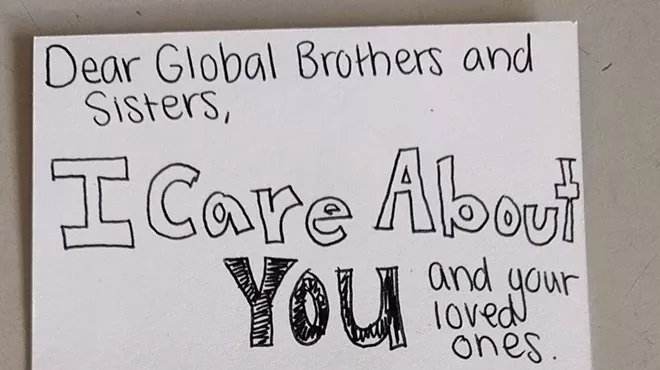

As the number of these children crossing the border has ballooned in recent years, the system has bogged down and children have stayed in the country for as long as 500 days before getting a hearing. That's what's prompted Obama to ask Congress for extra money to house the children and increase personnel in the courts tasked with hearing their cases, and what's stoked anti-immigrant sentiments across the country. For Gregory Cunningham, the program director at Catholic Charities Spokane's Refugee and Immigration Services, the ongoing debate is as much about how we treat those in need as about economic policy.

"If you dehumanize them, it's easy to say, 'We've just got to get them out of here.' It's like an infestation of bugs or something," Cunningham says. "If you put a human face on the other, then all of a sudden you feel an obligation to help, but if you can keep them at arm's length, it's easy enough to just say they're a nuisance and deal with them only from an economic or legal perspective."

Without a guarantee that they'll see the refugee assistance funding renewed, Cunningham says Catholic Charities is likely to look for local donations to its programs. Otherwise, both Catholic Charities and World Relief may soon start charging refugees for some of their services.

"The need is not going to go away," Cunningham says, "just because the contract did."♦