Monday, June 27, 2016

One group wants to save the butterflies at Riverfront Park — the really big ones

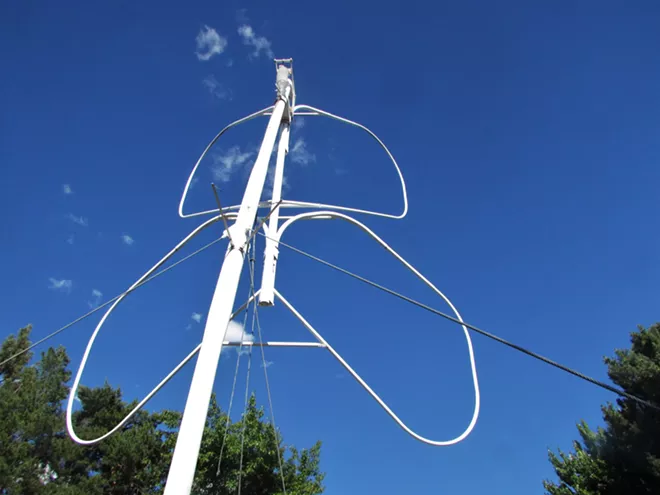

By now, all that's left standing is a single butterfly skeleton at Riverfront Park. Another's dismantled, stuck in storage.

This week, we have a story about the attempts of Riverfront Park's former manager to save the IMAX Theatre, currently on the slate for demolition as part of the park's major renovation.

In the meantime, however, others are fighting similar battles for their own beloved pieces of Riverfront Park. Spokane resident Jennifer Leinberger and a flock of others want to once again raise up the butterflies that stood tall during Expo '74. Every month she attends the subcommittee focused on the park's renovation, hoping that at least one butterfly can be saved and restored to its former glory.

"Riverfront Park, in general, is the jewel of the city, and Expo created that,"

Her Facebook group "Save the Expo Butterflies!!!" has over 1,000 members.

There's a beauty in the white frame of the single butterfly that remains, but it's a far cry from what once stood as a defining feature of the park: Over each one of the five sections of Expo '74 loomed a giant butterfly, covered in brightly covered vinyl fabric to mark each area: yellow, orange, red, purple and lilac.

The book The Fair and the Falls describes how the flowers planted in each section, and the drawings of people and animals on the wall, matched each butterfly. They were designed to move to twirl with the wind.

But from the very beginning, the butterflies became a liability in the wind. Before the fair even started, a wind took an unsecured butterfly down, crashing it into a Washington Water Power truck. (Amusingly, the driver wrote that the cause of the accident was that a "butterfly fell on the hood.")

After the fair was over, one by one, the butterflies came down. By 1995, only two remained: The blue and the yellow — and the yellow one was ailing.

“They were real symbols of the fair,” then-Mayor Jack Geraghty told the Spokesman-Review. “They just don’t deal with

Leinberger was three during Expo '74. She and her friends have nostalgic memories about the butterflies at the park. It's embedded in her memory.

"If you were lost and you were a child, you would be directed to stand by a certain color of butterfly," Leinberger says. "To just throw away the butterfly, it would be sacrilege."

And she has historical precedent she can rely on: Back in 1972, a community group of preservationists called "Save our Stations" was so intent on saving the Great Northern Railroad Station they put proposals on the ballot to try to pay to restore and upgrade the station. They failed miserably.

But the builders of the fair heard the message. They compromised, deciding to save just one part of the station from demolition:

"It was a community group that saved the Clock Tower," Leinberger says. "If a couple people hadn't had voiced their opinion and stopped that from happening we wouldn’t have that iconic Clock Tower."

Expo '74 was about rebirth, she points out. Now, the name of preservation may once again help to save the butterflies. Earlier this year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers informed the city that it would have to come up with a plan preserve key parts of Expo '74. Amid this process, Parks Director Leroy Eadie indicated to the Spokesman that he'd like to restore the butterflies.

A little more than four decades ago, the butterflies were a symbol of the park's rebirth.

"Now," she says "the park is going through another rebirth," Leinberger says.

Tags: Expo , Riverfront Park , News , Image