Monday, September 26, 2016

Spokane's property crime rate officially plummeted more than 12 percent last year — but it's still pretty bad

Daniel Walters graph

Property crime rates per 100,000. The apparent plunge in property crimes in Spokane in 2005 is a bit deceptive — the county eliminated the Crime Check phone number that same year, making it harder to report property crimes. In 2008, Crime Check was established, and it rose back to its baseline level

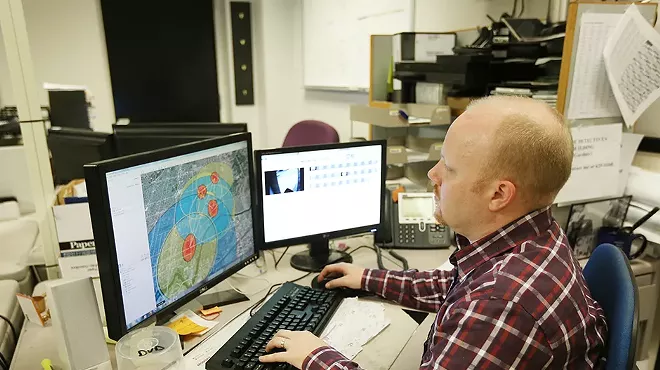

Looking at Spokane's internal CompStat reports, it appeared that the property-crime rate had fallen significantly from 2014 to 2015. But CompStat can be messy, plagued with redundancies and holes. For example, it doesn't include attempted property crimes in its total calculations, where the data released by the FBI does.

So for months we've been waiting, twiddling our thumbs, for the official data to come in.

Finally, the FBI released the national data last week, confirming about a 12 percent decrease in the Spokane property crime rate. Violent crime also slightly decreased by about 4.7 percent.

That's good news.

City Council President Ben Stuckart points to the more decentralized precinct model, increased funding for the Community Oriented Policing Services (C.O.P.S.) program, and the decision to hire more police officers as possible reasons for the improvement.

However, Spokane's property-crime rate still remains more than two times higher than the Washington state average and more than four times higher than the Idaho state average. Property crime still has not fallen below 2011 levels, before Mayor David Condon came into office. As we reported earlier this year, crime spiked up for several years after an announcement that the department was eliminating its property crimes unit.

Indeed, despite the famous decline in the crime rate since 2001, the city of Spokane has seemed largely immune to the nationwide trend. Instead — setting aside the years when Spokane eliminated its Crime Check service that allowed citizens to more easily report crime — the city's property crime rate has remained relatively consistent for the past three decades. It spikes up sporadically, before returning to a baseline of about 7,500 crimes per 100,000 people.

And so far, that trend seems to be continuing. CompStat data shows that so far in 2016 the decline appears to have halted. Year to date, property crime is up by 4.24 percent. While burglaries and arsons are down, larceny is up slightly. And vehicle thefts are over 20 percent higher than they were last year.

Last week, we pressed each of the police chief candidates on how they would solve the city's property crime problem.

Acting Police Chief Craig Meidl, who the mayor chose to again appoint today, suggested the problem wasn't just the comparative lack of police officers in Spokane — it was the lack of resources for community programs like drug rehab.

City Spokesman Brian Coddington says that the mayor is glad to see crime falling, but he knows there's still a long way to go.

"That’s one thing everything agrees on, whether you're a council member or you’re a mayor or you’re a police officer or you’re a member of the community," Coddington says. "There’s more work to be done on property crimes."

The mayor's recent program budget proposal includes the addition of four neighborhood resource officers, who'll be embedded within neighborhoods. They'll work with neighbors to identify problems, including nuisance houses or crime hotspots, and get them fixed more quickly.

Coddington also says the city is partnering with the local C.O.P.S. program to have volunteers man the desk in locations like the North Precinct office, freeing up more officers to go on patrol. The city will also seek to educate the public on ways they can make their homes and vehicles more resistant to theft.

Meanwhile, Washington state's infamous property crime rate slid down 6.5 percent from 2014. That means that Washington state is

A word of caution: The FBI discourages people from putting too much stock in rankings and comparisons with this data. Methods of gathering crime data can vary from city to city and state to state.

In some communities, police forces have been shown to have been "juking the stats" by, say, reclassifying serious crimes as less serious ones in an attempt to artificially create the appearance of a reduction in crime.

Similarly, if a community makes it harder to report

When it returned in 2008, the crime rate shot back up to its normal levels.

Tags: Property crime , News , Image