Friday, December 16, 2016

Sheriff Knezovich blasts suggestion that he shares blame for Spokane County's high property crime rate

Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich objects strongly to the suggestion that he can be blamed for Spokane County's high property crime rate.

Early last week, state Sen. Michael Baumgartner and Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich were clearly on the same team.

On Tuesday, Dec. 6, Knezovich testified in front of the Senate Law and Justice Committee about the depth of the region's struggle with property crime. In the spring, Baumgartner had read the Inlander's expose on the region's sky-high property

But when media reports came out suggesting that President-elect Donald Trump was considering Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers as the new Secretary of the Interior, the two men both announced interest in replacing her as 5th District representative.

And so, for the few days before Trump passed over McMorris Rodgers for Rep. Ryan Zinke of Montana, Knezovich and Baumgartner were competing for the same job.

"A lot of times these things become very awkward because you end up running against people you work with who you like," Knezovich said, at first. "Mike and I have always gotten along."

Knezovich noted that Baumgartner supported the bill the sheriff pushed that would have made it harder for a decision to fire an officer or deputy to be overturned if they lied or broke the law.

But Baumgartner didn't hold back on the criticism of Knezovich.

The senator had nice things to say about Knezovich, but also unspooled a litany of critiques: He pointed out that Knezovich hadn't succeeded in getting his police accountability bill through the legislature.

"I liked the bill, but Ozzie was unable to build much of a coalition behind the bill," Baumgartner says. "He just doesn’t have much experience in actually building a coalition to turn ideas into actual laws."

He suggested that Knezovich hasn't been battle-tested in a tough election. He noted that Knezovich has been pushing for a new jail for years, but has never been able to gather enough support for a tax increase to make it happen.

And then he hit a really sore spot. In recent years, the Spokane metropolitan statistical area — which includes Spokane, Pend

Baumgartner suggested that Knezovich's record, perhaps, could be partially blamed.

"That raises legitimate concerns about effectiveness here on the ground," Baumgartner says. "The buck has to stop somewhere with some of those issues. Ozzie has overseen an alarming level of property crime."

To put it mildly, Knezovich didn't appreciate that suggestion. The sheriff may not be the sort of guy who throws the first punch, but if he feels attacked, he tends to come back swinging.

"I’m surprised that Mike is trying to sling mud like this, especially when he doesn’t know the facts," Knezovich says. He points his finger back at Baumgartner's record.

"The state of Washington is the lowest state in the nation as part of officers per capita," Knezovich says. "For [Baumgartner] to sit there and say it’s the sheriff’s problem? ... Right back at you Mike."

And from this perspective, Knezovich argues that the $300,000 Baumgartner helped get Spokane to fight property crime is pretty thin gruel.

"That’s not sustainable. All that was was election-year grandstanding. What have you done, Mike, to help with property crime?" Knezovich asks.

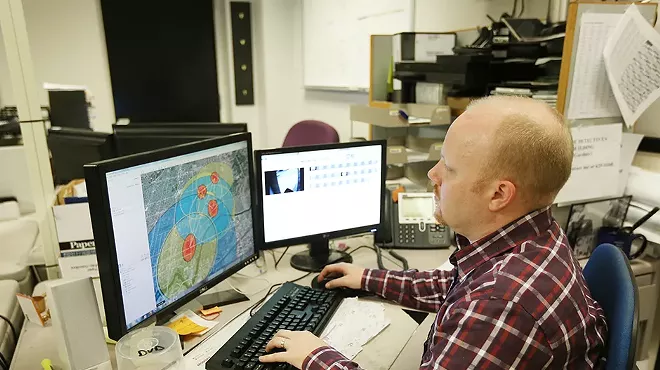

Not only did Knezovich run down his list of reasons why he thought Baumgartner was wrong over the phone Sunday evening, he walked over to the Inlander Monday afternoon armed with a collection of graphs and stats to drive home his argument.

Knezovich's case: With the circumstances he was facing and the resources he had, he managed to work miracles.

"Law enforcement is severely underfunded, especially in Spokane County," Knezovich says. "We've had almost a decade with 34 less staff than any other sheriff has had. I’ve still managed to keep property crime down... I don’t have a magic tax wand. I have to live within what I am given."

He provides stats showing that since 2004 — when the sheriff's office started tracking crime in Spokane Valley separately than crime in Spokane County — property crime rates in the Valley and the unincorporated areas of the county have been far below that of the city of Spokane.

"You know, the city of Spokane, that’s their own issue," Knezovich says. "That’s their record, and not the sheriff office's record."

He recalls a spike in crime at the end of

"In '12 and '13, I had to work my rump off reinstalling the confidence... that we were doing something about property crime," Knezovich says. He worked with junkyards to combat copper theft and put together a task force to crack down on residential burglaries.

Ultimately, the property crime rates in unincorporated areas have remained below the national averages, Knezovich says. Here's a graph laying out the last 11 years of stats on reported property crime. Click to enlarge it and read the annotations.

Violent crime has remained low in Spokane County, a fact Knezovich ascribes to the creation of the regional gang task force in 2007.

"Up until a year and a half ago, we were enjoying the lowest level of violent crime in Spokane County in 20 years," Knezovich says. "We’ve pretty much held violent crime at bay."

Knezovich suggests that Spokane's property crime rates may appear higher than other cities because many of them don't have a service like Crime Check, the number that easily allows victims to report smaller crimes over the phone. When Crime Check went away because of the loss of funding, the crime rate appeared to fall — a phenomenon that local law enforcement leaders refer to as the "Crime Check Dip."

"I'm the one who fought to bring Crime Check back, and I brought Crime Check back," Knezovich says.

He, too, is frustrated

"We actually got into some knock-down drag-outs over crime issues," Knezovich says. "I can’t make them do things. No other elected officials have been able to get them to do them either."

He remembers a time he was told to check with the jail captain to see if there were enough jail cells available before conducting an emphasis on rounding up property criminals.

"That’s a bad

He also directs his scorn toward state legislators, like Baumgartner, for not adequately providing funds to fight crime.

"You’re the one who refuses to give resources down at the local level to do things and get things done," Knezovich says. "You’re the one who cut the budget for [the Department of Corrections] where they don’t supervise people released from prison."

That last accusation, however, isn't accurate.

In reality, the vast majority of cuts to Washington state supervision happened between 2003 and 2009, before Baumgartner was elected to the state senate.

Still, Baumgartner was one of only nine senators to vote against a bill, based on a proposal from Gov. Jay Inslee, that would have reduced prison sentences slightly in order to pay for increased supervision for property crime offenders.

While the bill overwhelmingly passed the Republican-controlled Senate by wide margins, it failed in the Democratic-controlled House, partly because of a surge in pushback from law enforcement groups.

Knezovich himself wasn't a fan.

"The governor's plan would do one thing — increase the problem," Knezovich says. "You can't have it both ways. You can't reduce the time and just look at supervision. The supervision part is great for people that are going to comply. The ones that aren't going to comply... need to have more time."

But if the state isn't willing to reduce jail time to pay for increased supervision, it has to find the money somewhere else. And that, Knezovich says, is a problem nobody wants to deal with.

Baumgartner agrees that sentences need to be longer for certain property crime offenders and funding needs to be increased for offender supervision. And he thinks that's possible.

"We have more than 10 percent growth in our state budget," Baumgartner says, "We have a lot of money to spend. The challenge is

In particular, the state Supreme Court has determined that the state is unconstitutionally funding basic education. Fixing that could cost millions.

"I think the voters of the state would be much more comfortable addressing mental health, drug addiction, property crime and all these issues," Baumgartner says, and then addressing the education funding gap separately.

According to Inslee's office, the governor's latest budget proposal does add $15.5 million to increase community supervision caseloads, of which about 17 percent are property-crime offenders. But it's also packed with tax increases.

Baumgartner, however, has called the governor's budget "absurd and idiotic" and predicts it “would cripple small businesses and put working people out of jobs."

When it still looked like they were still going to compete for McMorris Rodgers' seat, Knezovich blasted this sort of thinking.

“If [Baumgartner's] going to fund the military like he’s funding criminal justice, I guess we’re going to be in for a long haul here,” Knezovich says. "He has been asked and he has done nothing."

Tags: Ozzie Knezovich , Michael Baumgartner , Property Crime , News , Image