Monday, January 9, 2017

The Idaho State Police won't release its confidential informant policy; what about other Idaho agencies?

Officially, the Idaho State Police policy manual does include a section that guides its use of confidential informants, but we can't see it. And neither can you. In response to a public records request, ISP refused to release Section 08.04 of its policies, citing a provision in state law that exempts "investigative techniques" from public eyes.

That means we have no idea how the state's police agency tells its detectives to navigate the controversial world of confidential informants.

"This is government transparency 101," president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation Wayne Hoffman writes in an email. "The public should be able to examine the policies,

ISP's refusal to release its policies is out of line with most other area agencies in Idaho and Washington. The Inlander requested confidential informant policies from 17 different law enforcement agencies in Idaho, including ISP, and three in Washington. Those responses reveal a lack of uniformity among the agencies that released their policies and contradicting interpretations of the Idaho open records law for those that didn't.

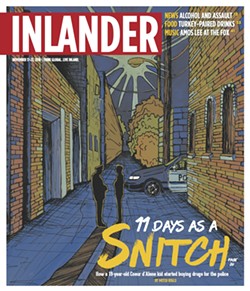

Last year, we wrote an in-depth piece about Isaiah Wall, a 19-year-old from Coeur d'Alene who died 11 days after he started working as an informant for the Idaho State Police. ISP brass would not confirm whether Wall worked for them despite overwhelming evidence. The Coeur d'Alene Police detective investigating Wall's death, however, did confirm his work for ISP."That a police department feels entitled to withhold that information after someone has died seems to be contrary to public policy."

tweet this

Alexandra Natapoff, a law professor at Loyola University in Los Angeles and a leading expert on confidential informants, calls ISP's refusal to acknowledge their role in Wall's life "quintessential aspects of that culture of secrecy.

"That a police department feels entitled to withhold that information after someone has died seems to be contrary to public policy," she says.

Eleven agencies in Idaho released their policies on confidential informants. Three Idaho agencies (ISP, the Bannock County Sheriff's

"The detectives assigned to that (task force) may use CIs and would do so following the policies and guidelines set forth by the FBI," Stinebaugh says.

Benewah County Sheriff David

All three Washington agencies released their confidential informant policies, and in fact, the Washington State Patrol even sent over a redacted copy of the contract with a CI (discussed in more detail below).

As far as the policies in Idaho that we are able to see, here are some major takeaways:

• Most policies direct police supervisors to consider at least three criteria — age, maturity, and risk of physical harm — before approving someone as a confidential informant. However, policies do not give officers any metric by which to evaluate the criteria.

Boise and Idaho Falls police departments do not list any such criteria.

• Most policies also talk about protection for confidential informants and officers. The Coeur d'Alene Police policy, for example, tells officers to consider whether giving informants tax forms to document their payments will jeopardize their safety.

The Meridian Police policy reads: "The department is extremely concerned that no person be placed in undue jeopardy. Realizing informing on criminal activity is dangerous, all safety precautions must be implemented." The policy also requires that informants receive the same level of surveillance and cover as commissioned officers.

The Boise Police policy, likewise, authorizes the use of a special unit for CIs' protection.

Pocatello and Sandpoint policies, on the other hand, explicitly say that absolute safety and confidentiality is not guaranteed.

From the Sandpoint policy: "Members of this department should not guarantee absolute safety and confidentiality to an informant." The policy manual does not talk about informant safety anywhere else, but it does give guidelines for when informants endanger the safety of officers.

• Most policies require some sort of written agreement, signed by the informant and at least one officer or supervisor.

• Most policies reviewed by the Inlander include a section on the use of juvenile informants. Bonneville County Sheriff prohibits the use of individuals under

The Pocatello Police policy manual says kids under 13 are not allowed, but the use of those 13 and older requires permission from a parent/guardian, an attorney, the court and the chief of police.

Idaho Falls Police bars juvenile informants except in "extraordinary circumstances," but does not define such situations. Juvenile informants must also be approved by a supervisor and have written permission from a parent or guardian.

Coeur d'Alene Police

The Boise Police policy makes no mention of juvenile informants at all.

• The Boise Police policy manual stands apart from all others reviewed by the Inlander because it does not contain a specific section on confidential informants. The 211-page manual mentions CIs at various points throughout, but guidelines are sparse. For example, the policy authorizes the use of a special unit to protect CIs during undercover investigations. It also states that officers do not have to report the arrest, detention or handcuffing of a CI if it's done as a part of a drug sting.

• Almost all of the policies include a list of criteria to consider in deciding the amount an informant will be paid, including the extent of the informant's involvement in the case, the risk taken by the informant, the amount of drugs and/or assets seized and the informant's criminal history.

The Pocatello Police manual (and others) specifically

Some policies go as far as spelling out a percentage of the current market value of drugs or contraband seized in order to determine the maximum amount an informant can receive.

For the Meridian Police, "the amount of payment will be based on a percentage of the current market price for the drugs or other contraband being sought, not to exceed 15 percent."

In Bonneville County, the narcotics unit supervisor and patrol lieutenant come up with an appropriate payment. "The amount of payment will be based on a percentage of the current market price for the drugs or other contraband being sought, not to exceed 15 percent," the manual reads.

• Generally, officers are not allowed to meet with CIs in private without another officer present or approval from a supervisor. Social meetings and intimate relationships are also forbidden in policies that discuss such interactions. Again, Boise Police policies give no restrictions.

As a comparison, the entire Spokane Police Department and Spokane County Sheriff's Office policy manuals, including sections on confidential informants, are available online. The Washington State Patrol sent over their manual along with a redacted copy of a contract with a CI, offering a peek into the inner workings of a traditionally clandestine practice.

According to the contract, the unidentified individual agreed to assist in vehicle and identity theft investigations and drug investigations. In exchange, WSP would recommend prosecutors go easy on the individual's hit and run and vehicular assault charges.

As part of the agreement, the individual was required to check in with a WSP detective on a daily basis, show up in person within two hours of WSP's request, wear a wire and introduce detectives to suspects at the whim of WSP and give permission to record the individual's phone conversations.

The deal required the individual to produce "THREE search warrants leading to THREE arrests involving felony level possession of stolen motor vehicles, possession of stolen property, identity theft of drug manufacture/trafficking/possession."

Natapoff, the law professor and proponent of informant reform, advocates for more transparency. She argues that the police should be required to collect non-identifying demographic and case type data so that the public can better understand who's being used as an informant and what kinds of cases they're making.

"If we require them to behave like any other public policy and hold them accountable in very standard ways, I think the culture would change," she says. "Police and prosecutors would no longer be operating in the shadows and they would have to justify their decisions. And once you have to justify them, you might have to start making different decisions."

Tags: News , confidential informants , Isaiah Wall , Alexandra Natapoff , Idaho State Police , Coeur d'Alene Police , Washington State Patrol , Idaho Freedom Foundation , Image