By Knute Berger / Crosscut.com / November 8, 2022

At the end of the so-called Nez Perce War in 1877, Chief Joseph pledged, "I will fight no more forever."

Those words made the chief famous, and they were seen as an indicator that a chapter had closed for Indigenous peoples in the United States as they were rounded-up and forced to live how and where the government willed.

But that was not the end for Joseph, whose Native name was Heinmot Tooyalakekt, translated as Thunder Rolling in the Mountains. After surrender, he waged a 25-year campaign to win the hearts and minds of the American people. And that effort brought him to Seattle one November weekend in 1903 to plead his case.

Joseph's words marked the end of a bitter fight to capture the chief's Nez Perce band and other non-treaty bands as they were fleeing to sanctuary in Canada. They had been dispossessed of their traditional and seasonal homelands. For Joseph, these were centered in the Wallowa Valley of northeastern Oregon, a stunningly beautiful place.

A flawed treaty process rammed through by Washington's Territorial Gov. Isaac Stephens in 1855 had used divide-and-conquer strategies to marginalize Native peoples. Joseph's father — also called Joseph — refused to concede the Wallowas. The government later promised them a place there but reneged.

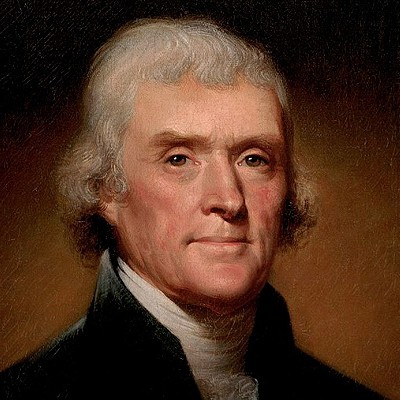

After Joseph's band surrendered, they were banished to Kansas, then to Oklahoma's Indian Territory where they suffered disease and deprivation. The move had violated the terms of their surrender, and Joseph demanded the government treat Indigenous people with the same rights and values enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Joseph's band was eventually moved to the Colville Reservation northeast of Spokane. But Joseph was not content to live in exile there.

The chief became a national figure. Old foes respected him for his military prowess — during their retreat, the Nez Perce had won nearly every engagement with the U.S. Army. Others say his real skill was as a leader and communicator. He met with presidents at the White House, he pushed Congress and bureaucrats to right wrongs against his people.

Newspapers spread his story far and wide. He was respected, though often valued as an impressive relic of what Whites claimed was a "vanishing race."

But Joseph did not vanish.

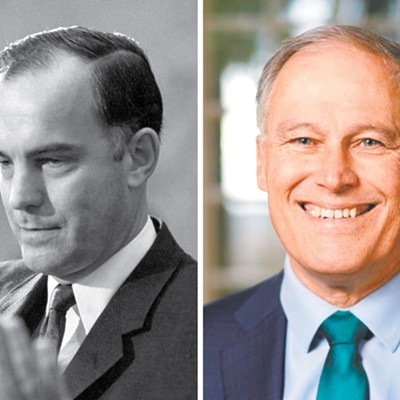

One man who saw him as an important historical figure was Seattle professor Edmond Meany of the University of Washington. Meany was determined to capture the state's early history, which was still within reach and living memory. He had done his master's thesis on Joseph and first met him in Nespelem, about 30 minutes north of Grand Coulee, in 1901. Two years later, he invited Joseph to come to Seattle and speak.

Joseph arrived at the Great Northern depot on Nov. 19, 1903. He was accompanied by his nephew, Red Thunder, and a former government administrator of Native affairs known as an "Indian agent," Henry Steele. Meany escorted them to their rooms at the luxurious Lincoln Hotel on Fourth Avenue. The chief had been to many cities, but never Seattle. His main purpose: "Chief Joseph will ask again for the Nez Perce lands ... Will not give up his fight," a headline read.

Meany started by showing Joseph and Red Thunder a different kind of fight: a football game. The day after their arrival, Meany took his visitors to watch the UW team play Nevada. They arrived on a jammed streetcar at Athletic Park at 13th and Jefferson. The game was epic, a hard-fought mud bowl with some 4,000 cheering people in attendance — said to be the largest UW football crowd to that point. Washington was victorious, the score 2-0. The team earned its first Pacific title with the win.

Joseph seemed baffled by the game but enjoyed it while smoking a cigar he'd been offered. He thought there would be more broken bones. "I saw White men almost fight today," he said in Chinook jargon. "I do not think this is good ... I feel pleased that Washington won the game." The chief laughed a lot, especially when the ball was punted.

After a day in the damp and a Seattle-hill hike to the hotel, the 60-something chief was exhausted. That night he was set to deliver his talk at the packed Seattle Theater. He was late, his speech was short. Through a translator he said: "My heart is far away from here. ... I would like to be back in my old home in the Wallowa country, my father and children are buried there, and I want to go back there to die. The White father promised me long ago that I could go back to my home, but the White men are big liars."

The following days were a whirlwind. Photographer Edward Curtis took pictures of Joseph at his studio. Meany took him on a tour of the city. He met Mary Ann Boren Denny, one of the city's surviving founders, and they conversed in Chinook, much to the chief's delight. He briefly addressed students at the UW's Denny Hall, where Meany also talked about the ill treatment of Joseph and the Nez Perce. But even sympathetic men like Meany still saw Native peoples as a passing race, not agents of the present and future.

Joseph's meeting with Mrs. Denny is a reminder that Seattle itself — a major city named to honor a local chief friendly to White settlers — is the site of unfulfilled Indigenous dreams. Chief Seattle's Duwamish people seek recognition while tribes have spent decades fighting for treaty rights, civil rights, sovereignty and human rights.

After a four-day visit, Joseph departed. He never got his Wallowas back. He died less than a year after his Seattle visit and is buried in Nespelem, where Meany spoke at his grave.

Joseph's struggle for justice, however, lives on. ♦

Knute Berger is editor-at-large at Crosscut, where this article first appeared. Visit crosscut.com