I am trying to define, to my students, what memoir is by showing what it is not.

Facebook is not memoir, I tell them.

Here's an example.

Yesterday I went to Albertson's for my first round of the vaccine. As I was taking off my coat, I asked the nurse if I might take a picture. She nodded, brought out the needle, and asked which arm. I told her my right, the one with tattoos. She aimed for the center of a spiral inked beneath my shoulder, and the picture was made.

I took the picture to post it to Facebook with a caption that read: First day of Spring and First round of Vaccine! I edited it carefully, cropping the nurse's face and my own, focusing on the needle piercing my skin.

It is easy to imagine the reaction from my friends. Hearts and thumbs up. Dozens of hugging emojis and comments to congratulate; admonishments to drink water and take ibuprofen.

But Facebook is not memoir, I reiterated.

I didn't post the picture.

The moment was nothing like what I'd cropped it out to be. In fact, I told the women on the screen before me, I still wasn't quite sure what the moment meant.

The truth is that I had not planned on getting the vaccine. That I had told my sister, a respiratory therapist who worked on the COVID floor of a major hospital, that I didn't want to get it. She begged me to reconsider.

That is not the whole story either. I wanted the protection. I watched the Frontline report on how the vaccine worked and Googled possible side effects, expanding the search to include conspiracy theories. I asked my most right-leaning friends if they were getting the vaccine, assuming they may be against it, and one replied, "It would be ridiculous not to."

I told my students that I had shots before. I used to have a weekly dose of B vitamins injected into my butt cheek, and my skin is proof that I can lie for hours beneath the tattooer's gun. My parents vaccinated my sister and me. Only a month before, my partner, a search and rescue volunteer, had gotten both shots, with barely a reaction, and I, myself, was encouraging my employees to do the same.

When I told my closest friend that I was afraid, she asked what I saw when I imagined getting the vaccine.

Mistrust and skepticism run deep in Native communities where medical racism is still prevalent.

I told her I saw people going in a building and not coming out and that I knew it was irrational, but something in me begged caution, like knowing when ice is too thin, something my DNA knew to fear.

"Oh, I totally get that," one of my students interrupts. "For Black people, we see government shots, and we think Tuskegee."

The class is primarily women of color; they start nodding.

"The government has been using Black people for experiments for years. Giving us Mississippi appendectomies and syphilis," the student said. "There's no trust."

The past and future collapsed in my mind. I recalled the stories I had read about Native women and government-sponsored programs practiced at Indian Health Service offices that sterilized thousands, a generation of children who would have been my age. I thought of smallpox blankets. Mistrust and skepticism run deep in Native communities where medical racism is still prevalent.

Another student, a Pacific Islander, joined the conversation. "Now it's about privilege. Those of us living in tighter communities with lower incomes that don't meet the essential requirement can't even get vaccinated. First, we are guinea pigs, then we are denied."

I understood this, too.

My co-workers and I had been working with the public since June 2020. We were considered nonessential, except to the nonprofit we serve.

"I tell people that this is a miracle of science, and I try to be brave. I want to be a role model," another student adds.

We all grow quiet, thoughtful.

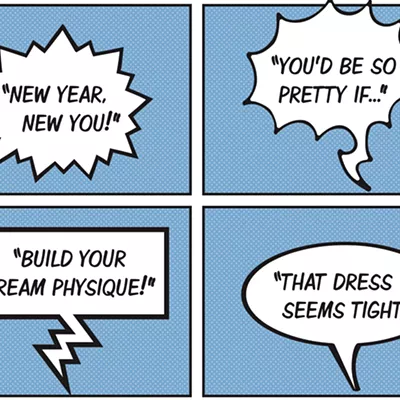

Memoir, I tell them, inspires conversation. It creates empathy and allows the writer to make discoveries while bringing her reader along. I ask if they understand, and they nod.

Our stories, I say, must illicit more than emojis. ♦

CMarie Fuhrman is the author of Camped Beneath the Dam: Poems (Floodgate 2020) and co-editor of Native Voices (Tupelo 2019). She has published poetry and nonfiction in multiple journals as well as several anthologies.