"Peace on Earth" is a nice, seemingly vanilla sentiment for a greeting card, but not too long ago it was a radical notion. In fact, the idea was treasonous a few centuries ago, and only became a "movement" these past 100 years. One turning point was the creation of that little symbol you see on all those bumper stickers.

That icon has a story, traced to England in 1653, when a religious leader faced death; to Spain, on May 3, 1808, when thousands of innocents were murdered by Napoleon's troops; and to 1958, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The story starts in 1648, when an odd young man named George Fox could be found preaching peace around London, but not in churches. He preached in markets, or in open fields. Europe's devastating 30 Years War was ending, and England's own civil wars were underway.

Fox's preachings caught the attention of the authorities, and he was imprisoned repeatedly. One judge got a laugh by saying Fox would "tremble at the word of the lord." Thus the name "Quakers" was coined, for the religious movement properly known as the Society of Friends.

By 1653, Fox and his challenge to English war-making was viewed as a real threat. Oliver Cromwell had Fox arrested and brought to London. Speculation was rampant that Fox would soon be found swinging from a hangman's noose.

The two men met, and, to everyone's surprise, Fox was set free. Apparently, Fox "spoke truth to power." In his recollection of the meeting, Fox wrote that Cromwell was taken by his brand of Christian worship, and "with tears in his eyes said, 'Come again to my house; for if thou and I were but an hour of a day together, we should be nearer one to the other'; adding that he wished me no more ill than he did to his own soul."

As we all know, war persisted. Although the 30 Years War was the last religious war fought on European soil, the nation states that rose up in its aftermath quickly found plenty of reasons to kill each other.

It was just 150 years later that Europe would be torn asunder again, via the Napoleonic Wars. One of the campaigns in those wars was the Peninsula War (1808-14), fought in Spain and Portugal. This marked another deadly twist, as it was named a guerilla war at the time — and is still considered the first such war by historians.

The painter Francisco Goya fills a unique niche in art history; he's considered perhaps the last of the old masters and also among the very first of the modernists. While beauty was aesthetic enough for the old masters, Goya added truth to his art. In the final years of the Peninsula War, Goya turned his eye to war. In The Disasters of War, he documented the atrocities being visited on his country with a photographer's honesty. Goya's conscience and skill allowed him to become the first modern anti-war artist.

Despite the atrocities of the Napoleonic Wars, humanity didn't learn much. After the 20th century dawned, the world was soon launched into another major war — World War I. Then a failed peace led to an even wider conflict — World War II.

Serving in that conflict was one U.S. Navy Commander, Albert Bigelow. While steaming back into Pearl Harbor on Aug. 6, 1945, he heard the news of a devastating new weapon dropped on Japan.

All these centuries of war and suffering were punctuated by these apocalyptic moments. Humanity had so perfected the art of war that it could now kill a city in a single moment. Wasn't this finally proof that war had to end?

Deeply troubled, Bigelow searched for ways to protest. Ultimately he found comfort with a religious group — none other than George Fox's Society of Friends. Through those connections, Bigelow and his wife Sylvia put up two women from Hiroshima who were in the United States to get plastic surgery, badly disfigured from the atomic blast.

Bigelow's faith and experience in war dictated action. In 1958, Bigelow and four others sailed his 30-foot boat The Golden Rule from California to Hawaii, with an ultimate destination of the Marshall Islands, where the United States would test another nuclear bomb.

Bigelow was arrested and jailed in Hawaii, but not before his mission gained widespread notoriety. Another Quaker, Dorothy Stowe of Vancouver, B.C., was so impressed by Bigelow that she borrowed his tactics for a little group she formed in 1971 called the Don't Make a Wave Committee.

Now we call that outfit Greenpeace.

As Bigelow sailed to oblivion, the people of the world saw for the very first time an odd symbol waving on a banner above The Golden Rule. The freshly designed nuclear disarmament symbol made its debut. Now we just call it the peace symbol.

Around the time Bigelow was out hunting Japanese subs around the Solomon Islands, an Englishman of fighting age was spending the war years working on a farm in Norfolk. Gerald Holtom, you see, was a conscientious objector.

In World War I, some 2,000 Americans who refused to participate in the war were locked up. Others with religious or moral misgivings have been allowed to serve off the frontlines, or as medics. In World War II, some 12,000 draftees who refused to participate were put to work in work camps. In England, there were 60,000 conscientious objectors during World War II, and they, like Holtom, were put to work at home.

Holtom was also horrified by the atom bomb, and he joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. An artist by trade, Holtom created a symbol for the CND to use for an upcoming protest. Basically, the design is intended to mimic the semaphore signals for the letters "N" and "D" ("N"uclear "D"isarmament), but when Holtom thought about it, the simple little symbol had deeper meanings, too.

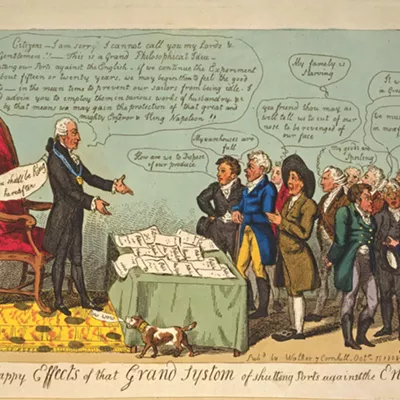

As he wrote to Peace News, Holtom said: "I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya's peasant before the firing squad [Actually, The Third of May, 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid]. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle round it."

Holtom finished the symbol on Feb. 21, 1958, and immediately donated it to the public domain.

Bigelow wasn't the only one to latch onto the symbol. The United States' student peace movement was afoot on college campuses at the same time. University of Chicago student and peace activist Philip Altbach visited London in 1960, and brought back to campus with him a bag of buttons with the logo on them. Who cares if they were designed for nuclear disarmament? It would do as a banner to fight against the Vietnam War, too. Or it could even be used to articulate solidarity over the Civil Rights Movement, as Bayard Rustin, an early adopter of the peace symbol, believed.

In the 1960s, Altbach's Student Peace Union reproduced and sold thousands of the buttons on college campuses.

Today, millions of items are covered with Holtom's powerful little symbol, just as the phrase "Peace on Earth" has been stamped onto the modern holiday season. It's almost become rote.

But in the weeks ahead, as you see those words, hear those words or say those words, realize that the phrase did not reach the public domain by accident. Across the centuries, George Fox, Francisco Goya, Gerald Holcom, Albert Bigelow and others took a radical idea and turned it into perhaps humanity's most profound statement of purpose. ♦

Adapted from an Inlander Holiday Guide essay first published November 23, 2006.