Domed blue arched over our drift boat as massive and colorful as the trout rising to our flies. Galaxies away from the ugliness of today's politics, I relaxed. As the sun rubbed the Bitterroots and my buddy and I charged the interstate toward showers and beers, he shattered my escape.

"Bill, you know politics," he said. "How do we fix our country?"

I yammered something about how the country's working as it's supposed to work, lamely explaining how when the people are divided, our government is designed to produce stalemate.

In other words, our government isn't working as we need it to. It needs fixing. Some 223 years after the adoption of the Constitution, it's time for some radical change.

Redistricting — the exercise of redrawing political boundaries every 10 years to ensure fair representation — is one process that needs reform. And it's playing out this fall in Spokane, and across the nation.

Daniel Walters' recent articles (Inlander.com, Sept. 28 and Oct. 6, 2022) lay out Spokane's redistricting decision. Similar mapmaking and upcoming court decisions across the country will partially determine whether we remain as politically polarized as we appear to be.

If more districts encompassed Republican and Democratic voters we might realize there is more space for consensus than the current system permits. Collecting like-minded voters into the same districts births polarization. If we want to come together as a nation, we need to forge consensus at the district level.

That requires mixing it up when redrawing voting maps — something incumbents and political parties loathe. They prefer to draw boundaries around like-minded voters inclined to give them a win. When district boundaries are drawn to favor a specific political party, it's called gerrymandering.

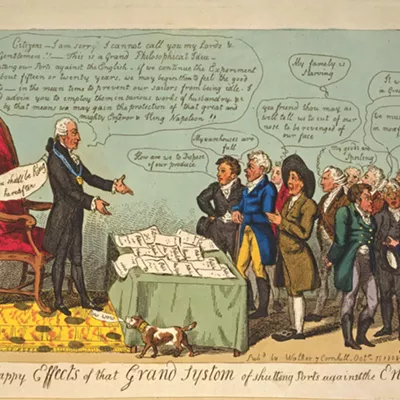

The term gerrymander dates to 1812, when Massachusetts drew a district in the shape of a twisting salamander solely to benefit one political party. Gov. Elbridge Gerry presided over that redistricting. Thus Gerry and salamander were combined into a term that 210 years later we still use to describe politically motivated district boundaries.

If more districts encompassed Republican and Democratic voters we might realize there is more space for consensus than the current system permits.

Since political boundaries are generally drawn by politicians, it would be naive to think voting patterns wouldn't be considered in their mapping. But in too many states, politics overwhelms the process. What should be an exercise in ensuring everyone is fairly represented is too often a competition to see which party can be overrepresented. Both parties play this power game with equal fervor and absence of shame.

In Washington state we avoid the worst of gerrymandering by turning over the redrawing of congressional and legislative districts to a bipartisan commission.

Washington's bipartisan commissions have eschewed drawing districts that egregiously benefit one party at the expense of the other. Instead, we get maps that provide both parties with "safe" districts of like-minded voters. Problem is, officials elected from "safe" districts have little incentive (sometimes a disincentive) to compromise. That leads to stalemate.

On the way home from Montana, regretting the lazy answer I dished my friend, I listed seven reforms that could re-energize our democracy. They include term limits, restructuring the U.S. Senate and overhauling campaign contribution rules.

That list also includes amending the Constitution so that federal congressional districts are determined federally, largely by an algorithm that divides the country into 435 equally populated districts, and when possible, into districts that include both Republican and Democratic voters. The algorithm should prioritize keeping entire cities and towns in the same congressional district. West of the hundredth meridian — the divider between the east and arid west — congressional districts should mirror watersheds. What's more, congressional districts wouldn't need to be confined within a single state. Coeur d'Alene and Spokane, for example, could be in the same congressional district.

Not everywhere, but in many places this proposal would require elected officials to listen to and represent a broader spectrum of voters, not just voters who agree with one another. That could result in the legislative compromises that fuel our republic.

Last week, Spokane's redistricting board chose a new map that keeps the current city council boundary lines largely intact. The recommendation is headed to the City Council, which will decide.

In Spokane and across the nation, I'd like to see maps of districts containing voters of different political leanings — in other words, across the country, maps filled with toss-up districts. That, my friends, would be one step toward fixing our country.

Political parties and incumbents will ensure that doesn't happen, but under the canopy of a Montana sky, a guy can dream. ♦

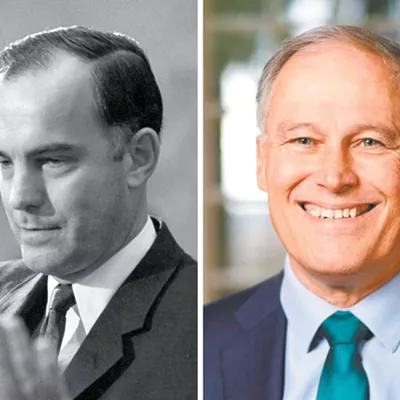

Bill Bryant, who served on the Seattle Port Commission from 2008-16, ran against Jay Inslee as the Republican nominee in the 2016 governor's race. He is chairman emeritus of the company BCI, is a founding board member of the Nisqually River Foundation and was appointed by Gov. Chris Gregoire to serve on the Puget Sound Partnership's Eco-Systems Board. He lives in Winthrop, Washington.