By Knute Berger / Crosscut.com / April 7, 2023

Ninety years ago, times were tough. The stock market crashed, banks were unstable, unemployment soared. The world slid into an economic depression. Northwest farms, timber camps and mines were hard-hit. Hoovervilles sprouted on Puget Sound; the hungry and unemployed marched on capitals in both Washingtons; climate refugees fled the Dust Bowl.

But in 1933 an ambitious effort to turn things around began, and it set off a decade of change that utterly transformed the Pacific Northwest.

Every day we in Washington state are still impacted by the New Deal, a multi-pronged program to lift America out of the Great Depression. In 1933, the newly elected president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiated a series of federal programs and agencies to provide jobs and build the country's physical and social infrastructure. In the West, it sought to pull the region from the frontier period into a new, modern century.

Its scope covered projects great and small, from building the massive Grand Coulee Dam to constructing outhouses for farmworkers. The New Deal's water projects resulted in irrigation that caused deserts to bloom into more fertile land. Power generated by the Columbia and Snake River dams boosted the region's industrial capacity, which would help produce cheap aluminum for Boeing and plutonium at Hanford. Millions of acres of land were remade or reclaimed, lakes created, towns and villages relocated or inundated.

The list of New Deal infrastructure work seems endless as the government sought to employ as many of the unemployed as possible, with jobs generated by local project needs. According to the University of Washington, the New Deal built or funded "28,000 miles of road, 1,000 bridges, 26 libraries, 193 parks, 380 miles of sewers, 15,500 traffic signs, 90 stadiums and 760 miles of water mains in Washington" alone. The bridges included the first Lake Washington floating bridge, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the Deception Pass bridges, and rebuilds of Seattle's Ballard and Fremont bridges, to name a few.

The Civilian Conservation Corps provided manpower to build roads, campsites, shelters and trails for national, state and local parks. A military-style organization, the CCC sent mostly young men into the wilderness to make it more accessible to the public, improve the environment, and provide unemployed youths with work and income. CCC crews fought forest fires, built lookouts and rebuilt the dikes which had been breached, displacing thousands, during the great Kelso flood of 1933. They planted millions of trees and installed utilities in places like Mount Rainier and the brand-new Olympic National Park, which Roosevelt signed into existence. An all-Indian division of the CCC was recruited to improve tribal lands. Black workers were hired too, though they worked on segregated crews.

New Deal agencies built schools, community centers, playgrounds, field and bath houses, post offices, waterworks, and sewer lines. They produced artistic murals and formed a Black theater troupe that put on plays in Washington. Writers were hired to produce detailed histories and guidebooks for each state. They landscaped the University of Washington, the Washington Park Arboretum and the Woodland Park Zoo.

They funded racially integrated low-income housing projects like Seattle's Yesler Terrace, among the first of its kind. They built airports in Spokane and Everett. They raised transmission lines for rural electrification. They built housing for migrant workers and helped resettle climate refugees.

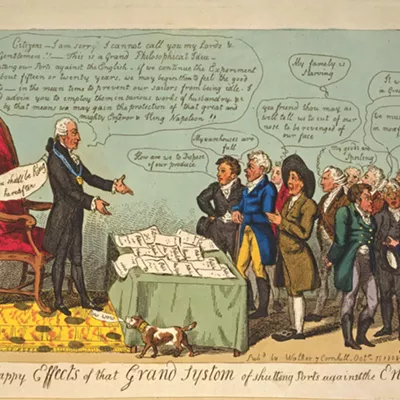

Their work was not without critics. A Republican candidate in Grays Harbor called the New Deal "Hitler in the Woods," claiming it would bring socialism to the timber business. The Communist Party argued that the New Deal was an attack on living standards and would fuel more imperial wars. Republicans criticized the spending and government overreach. Private power companies opposed public power projects like Grand Coulee Dam.

In 1937, Roosevelt came to the Northwest to see his New Deal in action. After a tour of the Olympic Peninsula, he visited Grand Coulee, the federal projects' colossal centerpiece. FDR believed hydroelectric power would transform the West's "wasteland." Whole new communities had been built for the dam's workforce, and the boomtown of Grand Coulee itself became known for sin and vice, earning the title "Cesspool of the New Deal." Nine towns along the river had to be relocated because of the project. An estimated 8,000 workers were employed building the dam. Twelve million cubic yards of concrete, enough to build a sidewalk that could circle the globe twice, went into it. Seventy-seven lives were lost in its construction. Today it irrigates 670,000 acres of land and produces 21 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year.

Smithsonian magazine has called Grand Coulee "the greatest monument to the New Deal's epic remaking of the American landscape." Folk singer Woody Guthrie was hired to sing the praises of New Deal dams. He wrote 26 songs in 30 days for $266.

But despite Woody's theme music, the New Deal had its downsides. Its dams did enormous damage to once-robust salmon runs, blocking the fish from returning to their spawning grounds. They flooded tribal lands and sacred places like Kettle Falls where Indigenous people had gathered for millennia. The environmental impact of large projects was largely ignored as ecosystems were disrupted. "Roll On, Columbia" today is about tragedy as well as triumph.

Grand Coulee enabled Hanford, which produced fuel for the bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki. Its waste will pose a threat for centuries to come. The atomic age and the industrialization of the Northwest have had impacts that will test our adaptability and quality of life for generations — perhaps even our survival.

Still, one wonders where we would be without the New Deal's upsides. We can take heart that we're capable of rising to huge challenges when crises arise, even those that were, and are, mostly manmade. ♦

Knute Berger is editor-at-large at Crosscut, where this article first appeared. Visit crosscut.com.

The Civilian Conservation Corps arrived in the Inland Northwest in May 1933, headquartered at Fort George Wright. By 1938, the Ft. George Wright District of the CCC was home to 260 companies stationed in camps across four states — Eastern Washington, Idaho, northeastern Oregon and western Montana — with roughly 42,000 members. Each company had a different "Work Project" aimed at improving the landscape, infrastructure, wildlife and forests adjacent to their camp.

— Elisheba R. Gearhardt, spokanehistorical.org