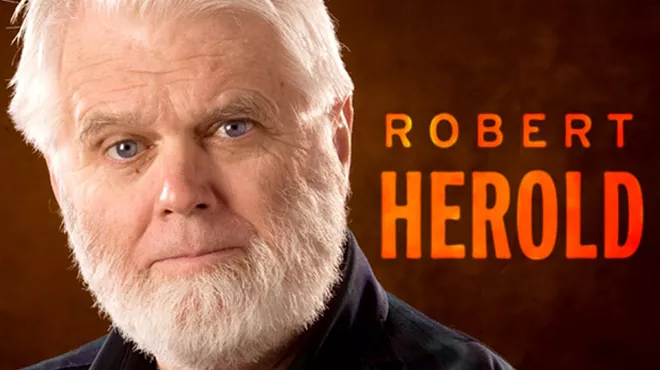

I first saw Robert Kennedy in person during the spring of 1956. I was a senior at Washington-Lee High School, located in Arlington, Virginia, just across the Potomac from D.C. At the time, Kennedy served as counsel to the Senate Committee on Government Operations. Our social studies teacher arranged a visit to Capitol Hill when hearings were being held; we spent most of the day in the gallery observing.

Joe McCarthy was the ranking minority member on the Committee for Government Operations. He no longer chaired this committee because in the midterm elections of 1954 the Democrats regained the majorities in both the Senate and House — majorities they had lost in the Eisenhower landslide of 1952.

McCarthy, in 1953, when he was chairman of the committee, appointed Roy Cohn to be counsel for the committee. He also appointed Robert Kennedy to the position of assistant counsel. (McCarthy was a long-time friend of Kennedy's father, Joe Kennedy, who no doubt had more than a more than little to do with his son getting the job.)

Following those losses in 1954, Republicans would not retake the Senate until 1980 (Reagan), and not retake control of the House until 1994 (the year Tom Foley lost to George Nethercutt). When Democrats retook both the House and Senate in 1954, committee members had been so impressed by the young Kennedy that they appointed him chief counsel.

So what did I learn that day about Robert Kennedy? Well, first about McCarthy: He rambled, badgered the witnesses, was incoherent and spewed out streams of unsupported accusations. (Accusations were obviously more important to him than were serious questions; most of his accusations were effectively ignored. I recall that the principal witness that day invoked his Fifth Amendment rights over 50 times.)

By contrast, Kennedy was the person on the committee who got the hearing back on track. He impressed all of us students with his bearing, the way he organized his thoughts and with his probative questions. In the decade to come, he would go on to be known for his even-keeled temperament and for wisdom beyond his years.

By 1956, when we saw the junior senator from Wisconsin during our visit, he was well on the road to infamy. "McCarthyism" had peaked in 1953. During 1954, he attempted what even then was considered to be stupid: He picked a fight with the United States Army. The 1954 "Army-McCarthy" hearings — all televised — exposed and ruined him.

Here's the story: David Schine, a McCarthy staffer, had been drafted into the Korean War and sent to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. There, Schine sought special privileges to avoid going to war, which were properly denied, despite inappropriate intrusion and pressure from McCarthy's henchman Roy Cohn. How did McCarthy react to this? He did what Cohn had coached him to do — he attacked by launching yet another smear campaign, this time accusing the Army of harboring communists.

He denounced the secretary of the Army and even told a general he was "not fit to wear the uniform." All this came right out of the McCarthy/Cohn (and now Trump) playbook. (Trump met Cohn, who became the future president's fixer, in 1971.)

Until those hearings, neither McCarthy nor Cohn had ever actually faced the American people nor been confronted by an adversary the likes of Joseph Welch, the folksy Boston attorney for the Army who concluded his remarks with this memorable line directed at McCarthy: "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?" The gallery exploded in applause.

In December 1954, following the Army-McCarthy debacle, McCarthy was formally "condemned" by his peers. An alcoholic, he died just a year after we saw him in 1956.

Robert Kennedy would go on to become his brother's attorney general, a choice that raised many eyebrows. He was just 35 and had no serious legal experience. When asked about this, Jack Kennedy smiled and joked, "I just thought Bobby could use some experience before he begins to practice law."

History will always remember him for his efforts during the Cuban Missile Crisis. When the missiles were discovered, the Kennedys formed the EXCOMM, the "Executive Committee of the National Security Council." The military wanted to bomb Cuba then invade. They were supported by the likes of former Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Chief of Staff Gen. Maxwell Taylor. The Kennedys disagreed; they wanted to give diplomacy a chance. They were supported by former Ambassador Tommy Thompson, who knew Premier Nikita Khrushchev personally, and by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who proposed a blockade. Robert Kennedy became the principle contact with the Soviets, and in the end he negotiated a compromise settlement, thus avoiding a nuclear exchange. It was the closest the world has yet come to armageddon.

Fifty years ago this month, Robert Kennedy was murdered in a Los Angeles hotel while running for president. He is sorely missed.