It's a long road from the little patch of Indian trust land called Frank's Landing on the lower Nisqually River to Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C., but Billy Frank Jr. blazed his own trail to Congress and is about to be recognized for that epic journey. The Nisqually fishing rights activist and environmental crusader will be enshrined as one of Washington state's two representatives in the 100-person gallery of historically significant Americans.

To understand Frank, it's useful to understand his father, Willie, whose own life was the guidepost for Billy growing up. Born in 1879, 10 years before statehood and less that 20 years after the hanging of his uncle, Nisqually Chief Leschi, Willie was raised by his aunt Sally Jackson, the Nisqually Tribe's last tamanawus woman, said to have had special powers and knowledge of Indian medicine.

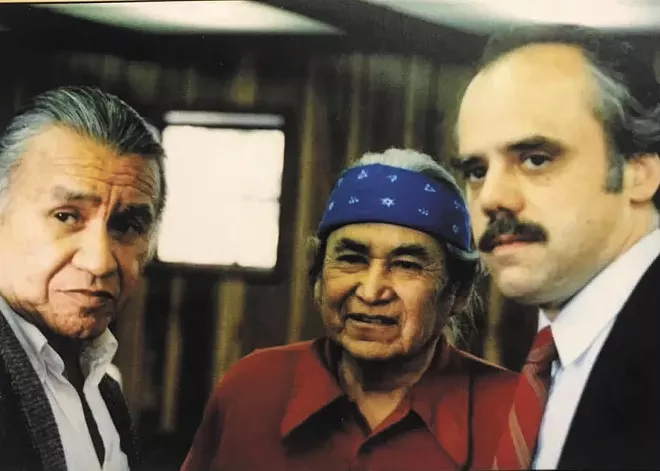

After Pierce County illegally condemned the Nisqually Reservation in 1916 to build Fort Lewis south of Tacoma, taking Willie Frank's 205-acre allotment, he refused to "take the money and go away," insisting the government purchase a six-acre wagon crossing on the bank of the Nisqually for his benefit. That land became Frank's Landing, the epicenter of historic battles over Native fishing rights that led to the 1974 Boldt Decision allocating 50% of each returning salmon run to the tribes, whose treaties with the U.S. preceded statehood. Tear gas and billy clubs became frequent invaders at Frank's Landing over the years leading up to the ruling, as did movie stars, camera crews and arrests.

Willie Frank's first arrest for fishing at Frank's Landing came in 1916, and over the years many more arrests followed. By the time Billy was born in 1931, going fishing and going to jail was a well-established part of life for the Frank family — a rite of passage for a Nisqually Indian fisherman. Billy experienced his first fishing arrest at 14 in 1945. Over the next 40 years, 50 more arrests followed, often accompanied by a beating at the hands of a state game official.

One of the great ironies of our modern era is that it took the testimony of Willie Frank as he was approaching his 100th year to help federal Judge George Boldt understand what the 1855 Treaty of Medicine Creek meant to the people whose lives would be altered forever by its signing. Their need to be allowed to fish, hunt, and gather seasonal roots and berries at their "usual and accustomed places" was the key to their survival.

Willie once observed: "I always say, the Nisqually Indian was living in paradise before the white man came. Everything grew just natural. There were lots of roots, wild onions, turnips and wild carrots. And one little black root that made all the others taste sweet. There was game, grouse, wild berries and everything."

Billy Frank Jr. continued that family tradition of helping us understand that it wasn't enough just to bring 100 years of "fish wars" to an end. Billy believed a new era required a new attitude by all stakeholders who cared about the salmon and its survival for our present and future generations. "Time is running out for the salmon" was his frequent refrain.

Billy adapted by leaving the river he loved to spend years trolling the halls of power in D.C., searching out allies who would join his quest to save the natural salmon runs for future generations.

He once said to me: "Thomas, when those politicians see me coming, I always want them to know that I'm coming to talk about the salmon."

And he always was.

Like his father, Billy Frank's life journey ended in the spring, in March 2014, when the mighty spring Chinook return to the rivers of the Pacific Northwest. For all of his 83 years, Billy never slowed down or rested, any more than the Nisqually River could ever stand still.

Now, Washington state has chosen to share the inspiring story of Billy Frank Jr. and his devotion to protecting the quality of life we treasure in the Pacific Northwest, by installing his statue in the U.S. Capitol Statuary Hall.

For future generations who want to hear his story, Billy Frank Jr. will be waiting there. ♦

Tom Keefe is a retired Spokane lawyer. His friendship with Billy Frank began while serving as legislative director for U.S. Sen. Warren G. Magnuson, in the late 1970s in the aftermath of the Boldt Decision.

BIILY FRANK JR. AT MARMOT ART SPACE

See a half-scale model by renowned Washington sculptor Haiying Wu for the 9-foot-tall statue of Billy Frank Jr. to be unveiled in 2025 in the National Statuary Hall. Wu's model will be on display through September at Marmot Art Space in Kendall Yards, beginning with a First Friday reception on Sept. 6 from 5-9 pm.

Frank's likeness in bronze will replace one of Washington's two existing figures in Statuary Hall, depicting the missionary Marcus Whitman, after state legislation was passed in 2021. A second statue of Frank is also planned to be installed in Olympia. Learn more about both the activist and artist — and the process to bring Frank to Statuary Hall — at arts.wa.gov.

— CHEY SCOTT