Art and community have gone hand in hand for millennia.

Spokane’s own art community has a long and storied history of challenge, change and success, but it’s always been there to serve artists and creatives in myriad ways.

Almost exactly 12 years to the day after the Arts Department was eliminated from the city’s budget, Mayor Lisa Brown is planning for Spokane Arts — the nonprofit created as a result of the elimination of the city Arts Department — to rejoin the city government.

The decision was announced this morning, Nov. 6, at a press conference in downtown Spokane.

“The arts in the city has been something that’s been significant for me for a long time,” Brown says. “Part of what I’ve always loved about Spokane was the richness of the creative communities. And so when I saw the arts move away from the city, I saw that as the wrong move.”

Brown says that Spokane is a “sports town” but also an “arts city,” and this move solidifies that sentiment.

“It gives us the opportunity to really double down on our support for the creative economy and the creative people in our region,” she says. “We will be able to identify new opportunities, give added stability to the arts infrastructure and find new and innovative ways to blend the arts into what we do.”

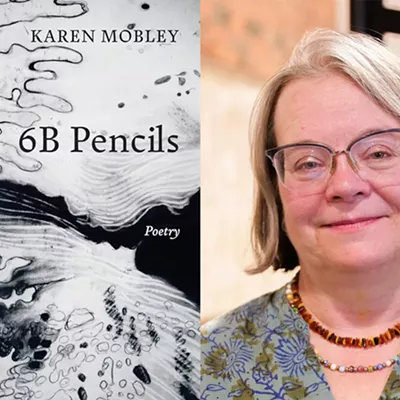

In 2012 the city Arts Department, at the time headed by local artist and art consultant Karen Mobley, was eliminated from the city’s budget by Mayor David Condon.

However, the city still had money in an art fund that was created for Expo ’74, which became the Spokane Arts Fund in 1986. In 2012, the fund became what we now know as Spokane Arts. For the past 12 years, Spokane Arts has functioned as an independent nonprofit with a board of directors and oversight from the Spokane Arts Commission.

Spokane Arts is funded by an admissions tax the city passed in 2007 to collect 5% on admission charges to concerts, sporting events and entertainment. The organization is also funded by contributions from community partners like Visit Spokane, the Downtown Spokane Partnership and the Spokane Public Facilities District.

One-third of the revenue generated by the admissions tax is disbursed to the Spokane Arts Commission. Of that amount, half goes toward grants, and half covers the operating costs of maintaining the Chase Gallery in City Hall, the city’s public art collection, and running the Spokane Poet Laureate program.

This model is set to change, however, as Spokane Arts extends its contract with the city for the first six months of 2025 and enters a “discernment process.” During that period, Brown’s staff and the Spokane Arts team, led by Executive Director Skyler Oberst, hope to answer many logistical questions that still loom.

“During the next several months we will be working together — representatives of the administration, Spokane Arts and the Arts Commission — to determine which portions of the existing Spokane Arts portfolio will come directly into the city office and how the partnership will work,” Brown says.

Under Brown’s proposal, the new city-run department would exist under the Division of Community and Economic Development. The official name of the department remains to be determined, though Brown referred to it as the “Office of Arts and Culture” at the Wednesday morning press conference.

“I actually think it’s a really smart move from an economic development perspective,” Brown says. “There are projects and initiatives that city government can either lead or help create funding for in partnership with arts organizations.”

During the six-month discernment process, Brown says the intention is to focus on how the new Arts Department will be structured, including what positions are needed.

Oberst was appointed as Spokane Arts’ interim director in October 2023 following the June 2023 departure of former Executive Director Melissa Huggins. One year later, Oberst says he’s finally settled into the role and is ready to face another transitional period.

In September, days before his first meeting with the mayor’s office to discuss the possibility of the city reabsorbing Spokane Arts, Oberst was working on a formal contract with Spokane Media Credit Union to provide funding to people on the nonprofit’s roster of local artists.

“We were really leaning into our work of investing in people, investing in the creative economy and telling our story well,” Oberst says. “You have to be careful what you put out into the universe and what you pray for, because I definitely prayed for a big opportunity for all of us in a community where the arts could be elevated and be more at the table. So, you know, part of it feels like destiny.”

Brown has assured Spokane Arts’ team that the move won’t be a detriment to their current projects.

“We don’t want to lose any of the current programming or people that are engaged with Spokane Arts,” she says. “At the same time, I think we want to understand how we could structure it to take advantage of the strengths of a nonprofit on the one hand and the city on the other hand, in partnership in the different initiatives. Because of our current budget situation, we want to start budget neutral. We don’t have a lot of new city resources to add to the equation, but we also don’t want to take resources away from current arts programming.”

Before Spokane Arts broke off from the city, KXLY reported in 2012 that the city was spending about $155,000 per year on its internal arts department. And before Spokane City Council voted in 2016 to dedicate a third of the city admissions tax to Spokane Arts, the Inlander reported that annual funding from the city had dwindled to about $80,000 per year during the nonprofit’s first few years.

Neither Brown nor Oberst can say exactly how a city-managed arts department will be funded, but they say that plan will be solidified during the six-month extension period in 2025.

Spokane Arts’ current staff is small, consisting of Oberst and four other members: Shelly Wynecoop, director of grantmaking; Shelby Allison, public art program director; Devonte Pearson, operations manager; and Jeremy Whittington, program director. Of those positions, four are full-time and one is part-time. Mobley also works under contract with the nonprofit as a public art consultant.

Oberst is looking forward to what the city and Spokane Arts can accomplish together, but says the pivot from one direction to another and looming uncertainty for his staff leaves him feeling “somber” after a year of work in the role.

“My first thought was about the team,” Oberst says. “Every single one of them has come to Spokane Arts and put their heart and soul into what we do.”

If Brown’s plan moves forward, Oberst would be hired to lead the department, yet other civil service positions in it would be created (it’s not clear yet how many), and an application process for those jobs would open to the public.

Mobley, who was Spokane's arts department director for 15 years before it was eliminated in 2012, says the “bureaucratic environment” of City Hall isn’t for everyone.

“Skyler’s done a really good job of getting a pretty tight team,” Mobley says. “They’re all kind of rowing the boats in the same direction. Then this happened. And so then there’s all these people who kind of have to reevaluate their lives in relation to, ‘What do I do now? Do I want to go to the city? Will I get hired by the city?’ There’s no guarantee that these people who are currently doing this work will be hired by the city.”

Transitioning from a nonprofit back to a city-funded department could create issues for employees as well as artists.

“The advantage to being a 501(c)(3), in my opinion, is nimbleness,” Mobley says.

She says the current nonprofit status allows Spokane Arts staff to more quickly make decisions than would be possible under the city, as it’s unencumbered by various policies and procedures.

“The last thing I want to do is give [artists] more paperwork to figure out and more bureaucracy,” Oberst says. “So that’s my belief, and I think Lisa and I share that vision that creatives need to be creating instead of messing with paperwork.”

Pre-2012, the Spokane Arts Fund coexisted alongside the city arts department for 25 years. There’s still a possibility for that with Brown’s proposed new structure.

Currently, Spokane Arts is based inside Visit Spokane’s downtown office on Riverside Avenue. Oberst says he expects being “in-house” at the city will make it easier to work and communicate with other departments.

“We’ll be in the conversations and we’re right down the hall if they have a question,” he says. “We’ll be able to come to an agreement really quickly, which, to be honest, is good government. It’s how it should work.”

Even though the Spokane Arts team recognizes numerous benefits of rejoining the city, they’re still concerned about the potential department’s stability and long-term future.

“If an arts department can be pulled out of the city that means we could be pulled out again,” Oberst says. “So that’s something that we really need to address through our discernment time.”

Brown says embedding the department within the city’s Division of Community and Economic Development would only solidify its existence.

“I think that the arts have always been about economics,” she says. “And we will be demonstrating that, I think, very clearly, in a way that will make it compelling to make it go forward. I will say, though, that you can’t provide for all contingencies that could occur in the future. But that’s true for literally everything in a government framework in which people get elected, because part of them being elected is to reflect priorities of the public.”

From the start of his tenure, Oberst’s top goal has been figuring out how Spokane Arts can help local artists comfortably live and retire in Spokane. He says these aspirations won’t change despite this shakeup.

“What I’ve learned about working with creatives is that no matter the weather, no matter the political climate, no matter what’s going on, I’ve learned a lot in that you have to see opportunity in everything,” he says. “And that’s a beautiful place to be. If we’re at the city, and we have more opportunities to serve others and invite people to see the world in living color, I think we’ll be better off, for sure. The work continues regardless of where your desk is.”