An interview with Linda Lawrence Hunt, who saved the story of Helga Estby

[

{

"name": "Broadstreet - Instory",

"component": "25846487",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "4"

},{

"name": "Broadstreet - Empower Local",

"component": "27852456",

"insertPoint": "8",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "8"

},{

"name": "Broadstreet - Instory",

"component": "25846487",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "12"

},{

"name": "Broadstreet - Instory - 728x90 / 970x250",

"component": "27852677",

"insertPoint": "18",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "18"

},{

"name": "Broadstreet - Instory",

"component": "25846487",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "23",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "24",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

This week’s cover story is the Inlander’s first-ever illustrated history, which tells the story of Helga Estby, who along with her 18-year-old daughter, Clara, walked from Spokane to New York City in 1896 in the hopes of winning a $10,000 prize from a mysterious benefactor. Read our story to see how their trip turned out.

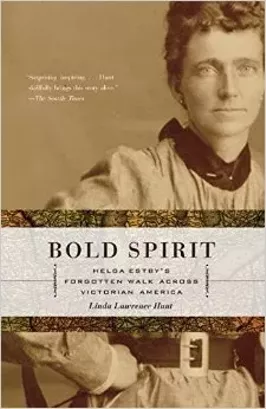

Part of our research for the project included the book Bold Spirit: Helga Estby’s Forgotten Walk Across Victorian America by local author Linda Lawrence Hunt. We sat down with Hunt to discuss her book (available to purchase locally at Auntie’s or via Amazon) and why the amazing story was ever lost in the first place. Here's an edited transcript of our talk.

How did you come across this story? Your husband was a judge in a history essay contest, right?

It was amazing. He was judging for the Washington State History Day contest that eighth graders write in, and he says, ‘You’ve got to read this story.” It was 11 o’clock at night and I was grading freshman papers — I was a Whitworth writing professor at the time — and I said "Oh, no, I don’t want to read eighth grade papers." But I was electrified.

I’ve taught women’s history and I knew how unusual what she’d done was. I think our lives are shaped by the questions that we ask. The question that came then, immediately, was whatever gave Helga the confidence and courage to make her think she could do this? The audaciousness of doing that in the 1890s was unheard of.

Where did you go after the essay?

I connected with Thelma and she’s the granddaughter of Helga and she’d lived with Helga. The story only got saved because of a scrapbook that had the StarTribune article and other articles from along the way. This little scrapbook that had been hidden for years and years and years...

After her husband died, they lived in the family’s home on Mallon Ave., she had a couple daughters living in the house, but Helga had a room upstairs. When Thelma moved into the house, she saw Helga writing in that room. She told Thelma that she had to save the story for her, but never talked to the children about what had actually happened.

And her daughters burned hundreds of pages of that manuscript right?

Hundreds and hundreds of pages. The daughters burned it, but one of the daughters-in-law kept the scrapbook secret from her husband, who was still upset that his mother had taken this walk. But once the son died, the daughter-in-law gave the scrapbook to Thelma.

Once you had somewhere to start, where did you start digging?

For years, I started working to create her route the best I could tell from the newspapers. In those years, I had to go to places to look for newspapers, but a lot of fires have destroyed libraries over the years. I first wrote an article in a magazine, and then I was going to drop it, but her story haunts you. So I decided that I wanted it in the historical archives because I didn’t want it lost in history, knowing women’s history and I knew that know glossy magazines come and go. But Columbia Magazine is archived in the libraries, so I wrote them if I could do a story and by then I knew a little more.

I went down to Idaho and saw some of the area around Boise and the place around the lava beds where she got lost and could have easily died. And after the article I thought I’d drop it, but I got a small grant to go to Minnesota and see her small sod home and knew I wanted to do a book....I also went to Norway to research there and talked to the Oslo newspaper to see if they’d put something in the newspaper and put a big article with a color picture and out of that I received a lot of help with the local historical society.

And then you studied Helga for your doctorate, right?

Yes, at Gonzaga a doctorate of educational leadership. The wonderful thing about the program is that they like you to work out of your passions and your field. Whenever they’d give me an assignment, I’d often write about Helga. Pretty soon they asked if I wanted to write about this for my thesis. I was thrilled and took the next two or three years working on the book.

The question I’ve been waiting to ask — do you think there ever was a prize or a sponsor with the $10,000 in New York?

That’s a good question. My own instinct is that there was a prize offered. It was fairly common in that era to have wagers like this. The newspapers did it to get people to keep reading. I think the sponsor assumed they’d never get there and they’d never have to pay it. That was a lot of money then. Maybe $200,000 or more.

But why is there no record of the sponsor?

That was the hardest part of the whole mystery. I’ve gone down every rabbit hole trying to figure out who the sponsors are. One thing I liked is that the sponsors appear to be women, so it's not a gender war story. The one thing that’s almost cruel is that they not only used the fact that they were a few days late as an excuse to pay, but it’s the middle of winter and they didn’t give them women two train tickets home. They were no longer novelty in New York by that point. They were just two immigrants with no male support.

Couldn’t they have just walked the whole way without an actual sponsor just hoping people would just feel bad for them when they got to New York?

The reason I wouldn’t buy into that is because it’s hard for us to realize how limited women’s options were in those days. This was so risky. To leave a family with that many children makes it feel like she was very, very desperate.

To me what was really, really scary for her was that the recession hit Spokane very hard. All these banks closed within a few weeks of each other. And [Helga’s husband] had been injured, the best I could tell, and couldn’t do his work. If they went bankrupt and you lose your home, where does a bankrupt family go? The threat to her was that they’d go homeless and come into Spokane and try to rent something, but who would rent to someone who just went bankrupt?

The whole family would have been split asunder so the desperation to save the family farm was for real. I don’t think you’d do this unless you were desperate. Now, no one ever asks me the other question, which is, was this a wise choice? I think she put herself in tremendous potential danger. I think it’s a miracle, practically. But it shows how strong she was that they actually made it.

Is there a possibility of a movie version of the story coming out?

There’s been strong interest throughout the years on potential television or film productions, but nothing is finalized yet.

Would it be important for you for the story to get to that level? Because it feels like a big part of your book is about saving this piece of history that was lost. Would something like a movie help solidify the story’s place in history?

I felt that doing the historical article and then the book I had a responsibility. I haven’t felt a pressure at all for it to get to film because it’s a natural for film, that would be wonderful. Of course I’d love to see it. I’d be thrilled.

What’s the most common response you get from readers who come across your book?

There’s a mix. Women tell me that Helga gives them a sense of courage to be bold in their own lives. If I go speak, I go talk about the silencing of stories and then people will come up and tell me about stories in their own families that have been silenced.

Now, 12 years later after the book has been published, are you surprised at how the book continues to intrigue people?

Well, I’m rather thrilled because of the strong interest that is still occurring and that I’m still getting requests to be part of a phone call for a book club in the Midwest or somewhere and get people’s reactions. Mostly, I’m happy to be bringing the story back to life when it was almost lost.