When I left my hometown, I took a jar of dirt with me. It wasn't large. Just a little glass container with rubber around the lid and enough soil to sink two, maybe three fingers into before hitting the bottom. I wasn't superstitious and I wasn't going to do it at all until I went to Meg's house for dinner the night before my train left. Like always, I was dead sober and she was on her third glass of Merlot. Her lipstick—a light mauve only a shade or two off from her foundation—left a faint spongy pattern around the rim of her glass.

"Wait, Vee—" She brought both palms up to either side of my cheeks and pressed in. "I can't believe I didn't think of this. You're leaving single."

"I guess so, yeah." Meg was insensitive on her best days, but I really couldn't reconcile her excitement over this with the truth of it. Single meant one thing: glitzy cocktail dresses, drunken mistakes, a bubble of extended girlhood. Maybe that's why the word widow was invented. Something had to close the gap between that and what had happened to me: my husband of six years in a body bag in our driveway, the ambulance going slow around the corner, its windshield wipers barely keeping up with the rain. Hours after it was over I noticed his reading glasses were still set open on the kitchen table like a metal bug with two round eyes and no wings.

"I can't believe I didn't think of this. Come on. Come with me."

Meg stood up too fast, I could tell. She wavered for a second, tugging her white tunic down. So many women here only wore dark colors: black, sometimes navy. I did. It was a way to protect against leaks without having to spring for those extra thick pads designed to soak up loose lactation. Meg did neither. She went braless under white cotton and if puddles formed under her shirt she barely noticed. A part of me always wondered if one day she'd drink so much the leaks would be purple and then everyone would know how she spent her evenings. Not that there was really a law against it. We were all pretty sure that they had a filtration system that took out any alcohol or trans fat or GMOs or whatever, but it still felt wrong so most women didn't drink.

Once she'd collected herself, she grabbed my wrist and guided me out to the garage. Most couples had theirs set up like this: fridge against one wall, a kind of rocking chair in the corner — some holdover from back when nursing rooms meant you had a baby to soothe — and then the sink and the medicine cabinet. One of Meg's pumps was on the dish drain in pieces.

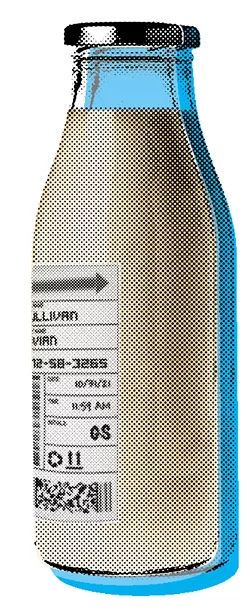

She flung the fridge open, revealing the neat rows of labeled bottles. Each had a printed label with her name and social security number and then a hand-written blank for the date and time. Before they got loaded into the car her husband would initial them with a black Sharpie.

"Why are you showing me this?" It didn't make sense, but anytime I looked at another woman's milk it made me feel like I needed to pump. Brought up the violent fullness, that top-heavy sensation we'd all gotten used to by the time we were eighteen.

"What does this look like, Vee?"

"It's your fridge. Hey, if this is going to be one of your lectures about oppression and..."

"No, not a lecture." She slammed the fridge door shut. She stumbled over the rocking chair, scooted far to one side and patted the space next to her. "Come here. Did you ever hear about the curse? The curse surrounding this town?"

I fell into the chair next to her. We tipped back together. There wasn't really enough space for both of us. Our legs pressed together: mine covered in the dark denim of jeans, hers bare, her loose skirt riding up to her waist. "What curse, Meg?"

"Everyone knows. When you leave this town, you have to take a jar of dirt otherwise you'll be forced to return."

"Okay, yeah, maybe I've heard that. But —" I brought one hand instinctively to my chest, checking for dampness. "What does that have to do with your milk?"

"If you get on a train tomorrow morning with a jar of dirt and play the grieving widow, you can keep it. No questions asked. They won't search it. Especially if you start crying."

"Okay —"

"And then, you can hide anything you want in there. Say..." She jumped out of the chair, leaving me alone like the heavier kid on a teeter totter. She turned to her medicine cabinet and pulled down one of her orange bottles. "Say a mandatory lactation pill or two..."

"Did you ever hear about the curse? The curse surrounding this town?"

"Meg, that's crazy."

"Is it?" She twisted the top off of the pill bottle and dumped them out into her hand. "Or is it crazy not to? Think about it, Vee. Henry's gone. Rest in peace, obviously." She could tell I was about to interrupt her because she started talking faster. "But wouldn't he want you to be free? He won't be there to be punished for signing off on empty bottles. It will be at least a year before they find you a replacement in that new place and in the meantime, you send them something else."

"Something else?"

"I don't know, Vee, send them chalk in water or something. They can't really be checking every single one, and then you'll have a year." She planted her hands on either side of the rocking chair, leaning me over me so I dipped back until I was almost parallel with the poured cement ground. "A whole year. Can you even remember what it was like?"

"I mean —" I tore my eyes away from Meg to the sink and the disassembled pump.

"Just play the widow. You know, milk it a little."

"That's not funny, Meg."

She leaned off the chair with a remarkable gentleness, bringing me back upright and we were alone and still in that garage for maybe ten seconds before the door groaned open and her husband's headlights spilled across us.

* * *

After a death, the woman always left and got a new house in a new place. I'd never heard anyone question it except Meg, who loved to point out that when a woman died the man kept the house, waited there for a new wife to come rolling in on a perfume cloud from another town. Another way we're expected to be more fragile, Meg would say. They assume the grief will be too much for us. So the process never differed and when the police explained it to me after Henry's body had been taken away I was almost grateful for it. I knew exactly what to expect. There would be a few days, and then, when it was time, a pre-packed, locked suitcase would show up in my driveway with all of the things I was allowed to take and nothing else.

Stepping off the train at my new town with the jar of dirt in one hand and the handle to my roller suitcase in the other, I didn't make eye contact with any of the guards, standing in periodic posts along the station. I didn't say anything when one of them grabbed a young woman wearing a polka dot dress up from one of the benches and put the barrel of their gun against her low back and shouted for her to keep walking. I told myself it was because I didn't want to draw any extra attention to the jar but I knew that was bullshit, knew it in the wobble of my knees when one of them stopped me anyway. He grabbed me by the shoulder and twisted me back and I let my face collapse into the most feminine, droopy half-smile I could muster.

"Miss, you know I'm going to have to ask you what that is."

Play the widow. I forced myself to look up at the guard. Of course, all I could see was my own face reflected in his sunglasses, the brim of his hat, and without looking down, the gun on his holster. "This?" I heard my own voice break and wished Meg was there to hear how well I was doing. "This is from my hometown. I've been — I've always been married to the same guy and then he died and I — I learned about the curse —"

"The curse?"

"You know, a superstition." I stared hard at his face until my eyes started to water on their own, and then I let go of my suitcase and rubbed my knuckles against the lids, pulling down, trying to force out a complete set of tears. "Everyone knows about it. It's just something you have to do to shed misfortune, to — oh God, I'm sorry." Now I wasn't really trying to act. Now I squeezed my eyes shut and I really did see Henry's glasses on the dining table. And what else? A book? No, he didn't have a book out. It was something else. Newspaper, maybe. Everything got taken away so fast. "It was Henry who told me about it. Seems like I owe it to him."

"Uh, yes —" The guard turned away from me, shuffling his feet. "Okay, sure. Just — don't cry. Here —" He reached into his pocket and pulled out a light blue plastic bag. Like everything here, it had an arrow swooping across it like a grin. "Carry it in this and no one else will ask you about it. You know where you're going?"

"Yes. Thank you, sir. Thank you so much."

I stepped away with my bag and my suitcase and walked the rest of the way off the platform and to my new house without further incident. I thought the only thing I had to worry about was the guards. I thought that once my jar of dirt was protected in plastic branded by the corporation, nothing else could touch me.

* * *

The first day not taking my lactation medicine, I felt mostly the same. Maybe a little bit dizzier. I just wanted a phone so I could tell Meg how it went but nothing here was set up yet. Just the basic furniture and food. No wifi. I was alone with the jar of dirt but I didn't dare touch it except to slip the pills in. That very first morning, the guard looked inside the plastic bag and asked me about the dirt, but I only had to explain it once and then it blended into the house effortlessly. Meg was right. About everything. I should have been wearing white and drinking wine back when I lived near her.

Even though I knew it would be useless, I sat on the couch and turned on the TV.

Right there, in stunning HD even though there was no internet or cable, was the man himself. The CEO. He stood at the edge of a green field, a dilapidated, cartoonish looking barn behind him. His bald head prickled pink. He had the chain of one of the silver dog tag necklaces in his hand. I brought my fingers to my own, felt the engraving with my number and the loop of the laser cut bell shape. Meg never wore hers. I don't know why, but I kept mine on.

"Hi, there." The CEO spoke like him and I were in a confidential board meeting. "When my company decided to take on climate change, we knew there was only one place to start. Factory farming in the United States was one of the largest contributors to —"

I grabbed the remote off the side table and shut him off.

* * *

The second night, after I cooked myself the pre-portioned stir fry set up in the fridge, I laid down on the couch and stared at the ceiling fan until I fell asleep. Something was slightly off with it, so when it rotated around to the top it gave a little clicking noise. I followed the thread of that clicking noise into the dark until I came out the other side into silence.

A green field, but this time, the cows were back. They saw me in their space and they all turned at the same time. I knew I should be afraid but I wasn't, just kept walking toward them. The grass was tall. It scratched at the skin around my ankles and shins and I kept going. Was it still a stampede if you welcomed it? Was it still my body if it fed no one? The cows kept coming closer and they were loud. Louder than the train whistle or the pounding on the door every morning when the guards came to check my pill bottles and my trash cans.

The clicking.

The ceiling fan and the clicking came back and I snapped awake, sucking in air.

My whole body felt like it had been electrocuted, like every nerve ending was firing off at the same time. A nightmare. God, I hadn't had a nightmare since —

"Since you were sixteen and started taking the pills."

"My whole body felt like it had been electrocuted, like every nerve ending was firing off at the same time."

I jumped, throwing down the blanket I took from my bed to the couch and spun around. There, at the kitchen table (identically round as the one in my old house where his reading glasses sat after his body had begun decomposing) was Henry.

"Impossible. You're —"

"Dead. Oh, Vee." The light above the table was on, but the rest of the house was dark, casting strange shadows across the bottom of his face. I moved toward him but he pulled back. "No. It's best if you stay over there."

"Why —Henry, I —"

"Vee, I can't believe you would do this."

"Do what? The pills? I — it was Meg's idea. I didn't know they were suppressing nightmares, or whatever they were doing. I'll take them if you want me to, Henry."

"You don't know anything." I couldn't see him anymore but I knew from the tone of his voice he was shaking his head.

"Henry? Henry?"

I turned on every light like I could pin the eyelids of the space open but it was just me in an empty house with two doses of medicine inside a jar of dirt. The stunning stupidity of what I was doing hit me all at once. Chalk? There was no chalk here. There was nothing here I could use to make milk. There was nothing to camouflage myself. Of course Henry didn't want me to break the rules. It was always Meg. Meg pushing me to wear white. Meg with her Merlot and her careless, stringy hair. I ran to the bathroom and dumped two pills into my hand and threw them back. I didn't know if I would start lactating in time to meet the quota but it was worth a try. The medicine hit my blood stream fast, turning my whole body heavy and hard to move and I lowered myself into the bathtub and slept there until I heard the familiar knocking at the door.

* * *

With the medication inside me and Meg hundreds of miles away I could finally think clearly. I'd been acting rashly. I had been rude. I hadn't gone over to meet my neighbor.

I went first thing the next morning.

Sheila, a woman in her mid-thirties whose husband was currently driving her milk across the state, led me inside to a coffee table set with tea and cookies.

"Sorry, I didn't know you were expecting me."

"I've been expecting you since you got here. Didn't know which afternoon you'd finally come say hello."

There was a click of disapproval in her voice. The house was identical to mine and was identical to Meg's, but I couldn't for the life of me imagine either of them in each other's space. The cookies were delicious though. Little dollops of lemon shortbread. I didn't know what to talk to this woman about. "You ever think about —" I snapped a cookie in half and a few of the crumbs trailed down into my lamp. "No, nevermind."

"No, tell me." Her eyes were warm and better spirited now.

"You ever think about just — not making milk? What you would use to replace it?"

The woman froze with her teacup halfway between her plate and her mouth. "What on earth would compel you to ask me that?"

"Oh, nothing —" I shifted in my seat, ate one more cookie, and then left.

As I was stepping down off of her front porch, Sheila stood in front of her door with her arms crossed, her lips pressed together tight as a rosebud sprayed with too much insecticide so it wouldn't open.

* * *

At home, I put my jar of dirt and my pill bottle down next to each other on the coffee table. I looked between the two of them, and then got itchy. I turned the TV on, but it was the same looped clip. "Hi, there. When my company decided to take on climate change, we knew there was only one place to start. Factory farming in the United States was one of the largest contributors to climate crisis. No one had proposed a plan that was big enough, bold enough —"

"Oh, shut the hell up." I tried the button to change the channel, even though I knew the image would be the same on every one. An Andy Warhol print repeating itself through space. The CEO's little smile twisting up in the sun. "I said, shut the hell up." I turned the TV off and then threw the remote across the room.

If I could just call Meg, she would know what to do. I could tell her about the dream. I could tell her I think the pills were repressing something even as they brought the milk out. I could tell her there's a nightmare on the other side of the medication and I know how to access it. I could tell her —

Or I can call Henry.

I sat back against the couch with a start. Without the pills, I could see him again. I could explain everything and he could explain to me how he was both dead and in my living room. We had love, once. It was always more than his initials on bottles of milk. It had to be.

That night, I skipped my medication again and I dreamed of nothing.

In the morning, when the pounding came at the door I didn't even bother to close my robe before answering it. My chest was bare and the guard recoiled at the sight of me, bringing his hand up to his sunglasses. "Ma'am."

"Sir." I took my time reaching behind me, pulling the waistband around to the front.

"We got a report from your neighbor. Said that you were making concerning statements."

"My husband just died. All I can make are concerning statements."

"And we're very sympathetic to that, but we're going to have to have a closer look around this morning if you don't mind —"

He slid past me into the house and when I turned around to watch him, my eyes froze. There, back next to the kitchen table, was Henry.

He was standing with his arms crossed, staring at me. I knew that look. He had it sometimes when we got into an argument about Meg. He thought Meg should be more careful, that she was asking to get taken away and then Kyle would lose his wife. I always thought he was just worried about her. I thought.

He tipped his head to the side.

"Is there anything in this house that we should be aware of?"

"Pretty sure you're aware of everything." I stared at the guard. He couldn't see Henry. If he could see Henry, he would be addressing his questions to him. He'd jump into a different kind of civility. He'd say, sorry sir, I didn't know a new husband had been assigned here.

No, Henry was only here for me. I kept eye contact with him. There was a way to soften that look, but I needed to be closer to him. I needed to be able to put my hand on the back of his neck, to guide him into my face. That had worked, hadn't it? Once upon a time, he had responded to my body. He had laughed at my jokes while we cooked together in the kitchen. I'd watched him read the newspaper at the kitchen table and when there was a cartoon strip he thought I'd like he cut it out and put it on the fridge with a magnet. When the heart attack came out of nowhere as he was moving the trash can up from the street, it was like a dagger through a perfectly happy life, a tear in the universe. Wasn't it?

While the guard was in the bathroom looking through the bottles, Henry picked up the plastic bag on the table, held it up so the arrow pointed toward the window.

No, I mouthed. But he kept going. Reached inside, pulled out the jar of dirt. He brought it up over his head. The guard wouldn't be in the bathroom for very long. I closed the space between us and this time he didn't dip back and this time I had nothing in mind but the glass jar. It wobbled between both of our hands for a minute, but he was taller than me and his arms reached a solid six inches above my highest grip so I had to jump a little and flick at the base of it. With one high jump, my fingers made contact with the bottom of the glass and it flipped out and the glass shattered. The dirt spread across the table. The guard came barreling out of the bathroom and had his gun off his hip before he could see anything and what would he have seen? A single worm inching its way along, untangling itself from the clots of soil and the little white pills with the pink lines like ribbons around their waists. And me, alone in the kitchen where I had always lived. When the first shot rang out I swear it was timed with a ding on Sheila's oven. ♦

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born and raised in Spokane, Lauren Gilmore writes speculative fiction for YA and adult readerships. Her short story "Clotting" was featured in the HAUNTED edition of The Hayden's Ferry Review. She is currently pursuing her MA in Literature and Social Justice from Lehigh University where she is bridging her interests in the digital humanities, American horror literature, feminist studies, and writing pedagogy. Her reported and analytical writing has recently appeared online in Horror Homeroom and Collider.