Sharma Shields is in a bakery on Spokane's South Hill, bobbing a tea bag in her mug, looking to kill some time before her kids get done with preschool. Behind oval-shaped glasses, her eyes can burn hot, but the heat is offset by a recurring smile and stories that all seem to end in self-effacement and a sharp laugh.

Shields pulls a paperback book out of her bag and places it on the table with little fanfare. It's fresh out of the box from the publisher, she says, rubbing a hand over the small likeness of an ape-like creature on the cover that Northwesterners know well. In a matter of weeks, the title will be in bookstores.

The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac is going to further change Shields' life, which has been full of more peaks and valleys over the past few years than her book's mountainous terrain. This sort of sudden literary fame, by way of national magazines and interviews before her debut novel hit shelves, would rattle most 36-year-olds. Shields feels like she should be rattled. But things are OK, at least for now.

Shields, though quick with a hug and possessing a warm demeanor, is a pessimist, a skeptic, a believer that the world is a tough, vicious place. She loves fairy tales, but mostly the ones where something awful happens. A lot of awful things happen in her writing, because she's waded through some awful things — addiction, disease, guilt and humiliation, to name a few. Now a very good thing is about to happen to her, but she's not sold, even if big magazines like Entertainment Weekly have gushed about her book and a major production company already has secured the television rights.

She's written a monster of a book about monsters, some real and some metaphoric, that could only come from the mind of a woman who spent years trying to forget her youth and her hometown and just find a way to tell stories. In the end, she may have delivered a story that's more about herself than she ever intended.

"I'm thrilled that it's getting the attention that it is. I keep waiting for someone to stand up and say, 'She's a fake!' Maybe everybody feels that way a little bit. I'm always really skeptical about success. I'm always waiting for the other shoe to drop."

The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac spans more than 60 years and four generations over the course of 383 pages of storytelling that warps reality and rewards those willing to believe in its magic.

We meet Eli Roebuck as a child, serving cookies to a massive creature in an ill-fitting suit that his mother has brought to their cabin on the Washington-Idaho border. The thing's name is Mr. Krantz and he has wooed Eli's mother away from the family home and into the woods, leaving Eli to deduce that his mother left him for a Sasquatch. So he becomes a podiatrist (feet, get it?), starts a family in the city and then transitions into one of the region's leading authorities on the mythic beast, all the while not merely hunting for a Sasquatch, but Mr. Krantz himself.

You're allowed to believe in Sasquatch, if you'd like, but you don't have to because you're never sure what to make of Mr. Krantz. You also don't have to believe in lake monsters or witches or magic hats or unicorns in Shields' book, because you're prepared for whatever might come your way by the time any of those creatures appear. Which they do.

We see Dr. Roebuck age and become a father, then divorce and have another daughter, and soon the novel is occupied as much by stories of childhood pain and wonder as it is tales of apelike creatures. You'll set out seeing Dr. Roebuck as a hero in search of the beast so many Northwest kids grow up wondering about, but he's harder to admire by the page. It's the women in the book who carry the story.

"There's a lot about family love and forgiveness, and how we move on and how we think about others and our family," says Shields.

There's a lot of Sharma Shields here. She experienced some of the weirdness you'll read in the book. She's never gone after a Sasquatch, but a gypsy woman stopped her in Spain when she was studying abroad and gave her an unsolicited palm reading, informing Shields that the boyfriend she'd been obsessing over back home wasn't the one for her. The gypsy didn't curse her entire family, though, unlike in the book. Shields also didn't leave her baby outside to be swooped up by an eagle, but she did struggle with postpartum depression. She didn't ever tell a counselor that she'd hit a unicorn with her car, but she's seen a therapist for years.

The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac takes place throughout the region. You'll recognize places like Rathdrum and Grand Coulee, but you'll never see the word "Spokane." She calls it the Lilac City, but it's clearly Spokane. The name change allowed her to make her hometown an island of fantasy in a sea of reality.

"I think that was me playing with reality a little bit. I love 'Lilac City' because it sounds like a place in a fairy tale," she says. "I love the image it provides and the smell, but I wanted people to know that this was an Inland Northwest book."

It's a loving ode in many ways, but Shields hasn't always been on the best terms with the Lilac City. At least not the real one.

She was sitting on her bedroom floor, 17 years old and sobbing. It was 1996 and the man on the other end of the line was from the Spokesman-Review, the same reporter who had waited outside her house and appeared at her high school track practice.

She says he told her that because of her lies, she was going to go up in flames in the newspaper the next day. She sobbed and said she didn't lie about anything.

Yes, she had confessed that she'd been cited for a DUI coming home from a party, but there were a lot of lies and half-truths folded in there, too. She'd told the paper — and the Lilac Festival committee that had just seen her elected a Lilac Princess for Ferris High School — that she had one beer, her first beer ever. She'd had beers before, and more than one that night. She'd said she'd been pulled over for a broken headlight. In reality, the arresting officer said she'd almost hit the patrol car.

Inside the Spokesman's newsroom, there was debate over how to cover the arrest of a girl whose DUI arrest would have been irrelevant had she not won the honor of wearing a purple dress. Anne Walter was the editor of the Our Generation section of the paper, which featured high school writers from around the region. She recalls fighting like hell to keep the story off the front page.

Making things more complicated, Shields was the student editor for Walter, the wife of another Spokane literary celebrity, Jess Walter. For Shields, working at the Spokesman was the pinnacle of a high school career that also saw her become homecoming queen, student body president and soccer captain. But now the paper had Shields and her misdeeds on its front page.

Lilac Festival committee members fought among themselves about what to do with Shields. It was the sort of small-town dramatics you'd think Spokane would be above, but that didn't keep a couple of committee members from quitting in protest. Radio talk shows took up the issue and the Spokesman wrote about the committee's decision. Apparently people were reading, because when Shields opened her hometown paper on her 18th birthday, the entire Opinion section was devoted to letters to the editor, either in support of her or calling for her head.

"Protecting the Lilac reputation was far more important than forgiving this kid's mistake," says Walter, now a school counselor after 16 years at the Spokesman. "And it was tough to see a kid that age vilified in the newspaper where she worked."

Shields lost her Lilac Princess crown and finished up high school as quietly as she could. The sort of people who write letters to the editor continued to do so for weeks to come.

She enrolled in the University of Washington's honors programs and thrived on her newfound anonymity in Seattle, with Spokane and the mistake of that one stupid night a state's length away. With the novel coming out, Shields wondered if people would remember the ordeal. She still doesn't exactly know why it ever became such a circus, but she can make a guess.

"People love an Ophelia story. They want to see the young girl drown," she says. Part of her doesn't really blame them. She knows she screwed up.

But she learned to love Spokane again, and she's trying to learn to forgive the 17-year-old brat who drank and drove and lied, and then lied a little more.

"There will never be a time when I won't regret it. I'm not even sure I know what forgiving myself entails," she says.

It's been tougher than she thought, but there had to be some pleasure in dumping a Lilac Princess into Dr. Roebuck's Lilac City, complete with the overinvolved parents and crowded parade route. Her husband had suggested she include it one afternoon during a walk through the lilac gardens at Manito Park. It seemed like most people wouldn't care about a silly tradition in Spokane, Washington, but she did it anyway. And wouldn't you know it: that Lilac Princess ends up going up in flames — literally — about halfway through the book.

Sharma Shields never doubted that she would be a writer, but adulthood had a way of making her dream a little harder than she expected.

She spent a few years working in bookstores after graduating from the University of Washington. She'd been a devotee of the classics prior to that gig — "dead white guys" and the like, she recalls — but was now able to keep an eye on new writers.

Shields was accepted to the MFA program at the University of Montana, where she met Simeon "Sam" Mills, a graphic novelist and short fiction writer whom she would eventually marry. Shields wrote one novel during graduate school, another the year after graduation while slinging coffee. The second was a horrible detective novel inspired by film noir, one she never thought seriously about publishing.

She then found a job in Missoula selling tour packages to foreign countries, and was unexpectedly competitive in the position.

"I don't know why I was that way, but what's the saying, 'Always be closing?' I was all about that," she says.

While the gig enabled her to take a couple of trips abroad, the work was the sort of cubicle-and-headset drudgery that left her emotionally and physically exhausted at the end of the day, meaning she wasn't about to sit down in front of a different computer and begin writing. It was depressing, and she started drinking more and more as a result.

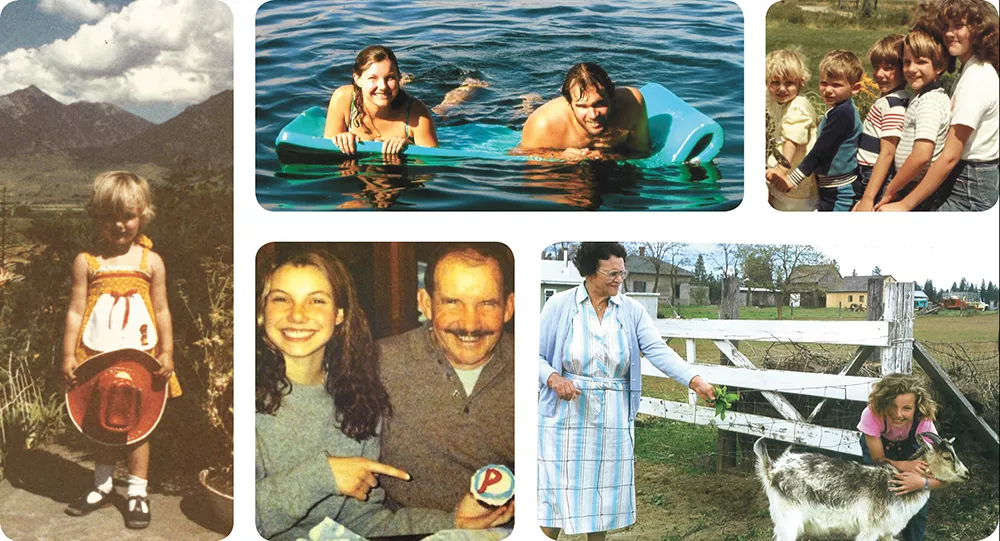

Mills had been teaching at the university as an adjunct and finding other odd jobs when there wasn't a spot for him, so after a visit to Shields' family cabin on a remote part of Lake Pend Oreille, they made a decision on the drive back to Missoula. They'd quit their jobs and be at the lake by Feb. 1, 2008, intending to rededicate themselves to writing. "Go lake, 2/1/08" became their mantra.

They actually did it, putting their life in Missoula into a storage unit and heading for the wilds of North Idaho in the dead of winter. But that winter was the one that all but shut down the Inland Northwest and they couldn't even get to the cabin, which meant spending a month living in Spokane with her parents. Panic began to seep into Shields' world.

"I had this huge fear that someone was going to recognize me in a grocery store and say, 'There's that lying, sack-of-shit princess' or something," she says, acknowledging the narcissism required to believe that such a thing might actually happen.

The panic attacks became so intense during that month that she tore muscles in her chest and developed a sense of agoraphobia. A lot of it was processing the guilt of her past, but there was more to it. She wondered if she and Sam had bitten off more of their literary dream than they could follow through with.

"It was a perfect storm of quitting a job and leaving my home in Missoula, which we loved, and uprooting in a day," she says. "Rededicating yourself to fiction when you don't know if you have any real talent is terrifying."

The snow receded some and the couple were ferried out to the simple two-bedroom cabin — accessible only by boat — by a loving old man named Lou who lived on their bay. Their days were spent writing and reading and taking long hikes into the woods. They'd watch movies and spend ample time reading. About once a week, Lou would take them across the lake, often in numbing weather, to shop in Sandpoint and peruse the public library.

Shields eventually pulled out her work from grad school and managed to land a number of her short stories in prominent literary journals. Her new writing took on the magic of the lake and the new stories were her weirdest yet, all of them cemented firmly in the Inland Northwest landscape she grew up with.

Winter seeped into spring and the clock expired on their retreat. They always figured they'd return to Missoula, which in their minds would always be their home, but they didn't go home. They went to Spokane.

Somewhat improbably, Shields was heading back to the hometown she still feared. But she found a job selling books at Auntie's, and another as an information specialist at the Spokane libraries. She managed her way into a literary community that welcomed her and her talents. No one yet has come up to her and told her she's a lying piece of shit. Instead, she's become a community leader, albeit a reluctant one at times; a mainstay at literary events and a champion for the city's booming writing scene. She even organized and hosted a woman-centered short story collection and reading event called Lilac City Fairy Tales, making her a mentor of sorts for many of the city's female writers. Along the way, she published Favorite Monsters, a collection of short stories that feature the spooky and weird seeds of the fantastical that would bloom in her novel.

"I think she's incredibly generous as a writer and a member of this community," says poet and Eastern Washington University instructor Ellen Welcker. "She is constantly promoting the arts and promoting the great things in Spokane outside of the arts, too."

You won't find the house Sharma Shields grew up in. Well, you won't find it in Spokane, at least. If you go to her childhood address at the top of the South Hill, you'll find a Target and an apartment complex. The house was lifted off its foundation and moved to another town. She'd like to go see the house in its new spot, and maybe bring her kids along for the weirdness alone.

But in her youth, her backyard went out into the woods. The daughter of a cardiologist, Paul, and a cardiac nurse also named Sharma, Shields grew up with a brother, John Paul ("JP" to her), one year her senior, and three older half sisters. Sharma and John Paul roared through the woods, the brother indulging his sister's fascination with Greek and Roman mythology, an interest that continues to make it into her writing.

"I was always Artemis," says Shields.

She always knew she wanted to write. By elementary school, she was whipping together a newsletter via the magic of a DOS program and circulating it to classmates. A story she wrote around that time predicted that she would become a famous detective during the day and write novels in her free time.

"There was never a time when she wasn't writing. If you want to buy into that concept of a calling, she found her calling very early in life and always wrote," says John Paul, a classically trained guitarist and instructor who performs throughout the region.

Both siblings say their parents were endlessly supportive of whatever the kids wanted to do. If they showed an interest in a subject, their mom came home from the library with an armload of books for them to study. Creativity was encouraged and storytelling was always part of the family.

There's always been a sort of darkness to Shields that began in her youth and extends to the pages of The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac, a book whose characters never get off the hook and are all chased by demons. Shields remembers her first bad dream, and thinks maybe that was the start of her life of thinking darkly.

It began with a schoolhouse perched on a hill, the bell ringing in the belfry, the wind gently brushing past her. Then the everything broke into puzzle pieces.

"I don't know where that comes from. I've always had dreams like that," says Shields. "I'm never being chased, but it's always something unsettling."

In her early teen years, her brother remembers her night terrors. She'd sleepwalk around her room and unleash the occasional scream. One night she stormed to John Paul's bedside, yelling that her parents were being murdered in the next room. She awoke the next day not having remembered any of it. To this day, she's unapologetic about her view that the world is a dark place.

"I really love people and I am a loving and affectionate person, which is good, but I do believe the world is a cruel place and it's unfair. Some of us are born luckier than others," Shields says, adding that she's one of the lucky ones, one of the "spoiled ones."

It's a couple of weeks before Christmas and Shields' 2-year-old daughter romps around the living room, sucking on a Popsicle, nursing a runny nose that's keeping her home from preschool with her 5-year-old brother. She sits on her mom's lap on a couch vandalized at some point by Magic Marker as Shields relays some good news: The novel's television rights have already been optioned by a production company.

This isn't a life-changer right off the bat, but it will make the approaching holiday a little more fun around the house, she says. And if it actually makes it through the mucky Hollywood path, it could be huge. A few weeks later, Entertainment Weekly would name her book one of the top releases to expect in 2015 and listed her as a star to watch. Accolades from O magazine and Marie Claire soon followed. All of this weeks before the book was even available.

Things have been good, but sometimes that's when Shields starts to worry. The good seems to always come with the bad. She sees it like a wicked seesaw that balances, or maybe unbalances, her highs and lows.

The bad tossed its heavy load on the other end of the seesaw one night in 2013. It could have been a scene from one of her stories — a woman stumbling through the dark forest, reaching for the light in the distance. But this was reality, and Shields was the woman in the woods. It was a writers' conference in the Methow Valley, and she was trying to make her way through a seemingly inconsequential patch of trees to a party for the festival's featured writers, a designation which included her. She wanted her brain to put her feet in front of each other, the way they'd dutifully been doing for more than 30 years, but there was a disconnect somewhere. Her feet were numb and she could hardly move. She stumbled her way toward the light and made it out, but in the coming weeks, the numbness she'd already been feeling in her arms would lead to an MRI revealing that she had multiple sclerosis.

"On one hand, there was the up that my book was possibly selling, and the down being that I now had this really awful disease," she says.

Those first few days, Shields was pissed. She'd see a television commercial with an old couple strolling happily together ("They were always for cruise ships or something," she recalls) and she'd figure that such a scenario would never happen for her. It made her think a lot about the future and her kids and all the novels she still hadn't written yet.

As if MS wasn't enough of a battle, the diagnosis was coming on the heels of Shields conquering another demon that had been chasing her around for a couple of decades.

Tears build under her glasses as she tells it, gripping her daughter tight to her chest.

"It makes me want to weep just thinking about it," she says, then blurts out an ugly truth: "I went to a play date and drove home drunk with my kids in the car."

She drank wine and beer and had a blast with the other parents. She had a lot — she's not sure how much — but her friends said she didn't seem out of control. They offered her to get her a ride home, but she drove. She remembers none of this.

Shields hasn't had a drink since. She's an alcoholic, she admits. Maybe not the whiskey-in-the-coffee sort of alcoholic, but drinking, and drinking to the point of blacking out, had become routine since her 20s. People, including her husband, worried about her, so there were times when she'd stop drinking. She also was sober for both of her pregnancies. Still, alcohol made its way back into Shields' routine, and after the night she drove with the kids, she figured her drinking was eventually going to kill someone. After a day spent puking into the toilet, she went to an AA meeting and made it through the brutal first 90 days of sobriety.

The drinking was wrestled to the ground, but MS was a new sort of monster.

"I had just gotten sober and felt that the rest of my life could begin, and then a couple months later I get this diagnosis," she says.

Each night, she gives herself a shot in the arm, and it hurts like a son of a bitch a few minutes after she punctures the skin. Still, she's never missed a day of shots. Her most recent MRI showed that some of the lesions on her brain are healing, and her doctors tell her that's progress. She's changed her diet and made a habit of getting out and walking most days. MS sucks the energy out of its host, so she's sure to lay down and rest every day.

For an admitted pessimist, Shields has an oddly positive perspective on her disease.

"I actually think the MS diagnosis keeps me grounded. Sometimes I get so happy about how my literary career has taken off that I feel like I could just float away or explode. I just get so elated about it; it's really cool to feel that sort of happiness," she says.

Shields has no shortage of reasons to be happy, and it's perfectly logical and sane that someone who wrote as good a book as she has would allow themselves that happiness. The loving mother doesn't always believe everything is going to be great, because a lot of times, she's found, it isn't. And she doesn't always trust the world.

"I'm a skeptic about everything by nature, including Sasquatch," she says.

She can't cure her MS or her anxiety or her guilt by writing a book, no matter how big an impact it makes on the literary landscape, and she can live with that. The real world, like the Lilac City in The Sasquatch Hunter's Almanac, can be a dark place. She's found a way to relate to that world through her writing, and there's some comfort in that.

"I think everyone struggles with something. Maybe that's really naïve of me to think. Maybe there are some people who are really buoyant and can do it, but what's really interesting about life is that we can love and let ourselves be loved, even if we have issues with ourselves," she says. "I think there's so much tension in the world, and I like putting my finger on the tension. That's what's fascinating to me as a writer." ♦

THE SASQUATCH HUNTER'S ALMANAC RELEASE PARTYSharma Shields reads from and signs copies of her new book. • Tue, Jan. 27 at 7 pm • Auntie's Bookstore • 402 W. Main Ave.