It only took a pinprick to summon the ballooning ruby droplets from his fingertip.

Human blood may be an unusual choice for the sake of creativity, yet artists across history have used it in their work. Inside a closet-sized darkroom, 23-year-old photographer and Spokane transplant Brian Deemy lets a minute volume of his own blood pool into a small glass bowl. Diluted with chemicals, these cells and platelets are then used to pigment a self-portrait. The resulting print of the artist's bespectacled face is tinted by a ghostly pink-orange hue.

Deemy is on a perpetual quest to push boundaries in his chosen medium, specifically alternative and experimental photography processes that typically don't involve any digital techniques.

"I always try and have at least two sides to my projects," Deemy says. "I can't not have this intrinsic commentary on the process in my work. For the general public, they're not going to catch that, but it's important to have another side of the image beyond the subject matter depicted, because [each photograph is] so labor-intensive."

In the earliest days of photography during the 1840s, a process combining the chemical substances potassium bichromate and gum arabic to print images from a negative allowed photographers to add any type of pigmentation. In Deemy's newest project — his senior thesis for a bachelor's degree in fine art photography that he expects to receive from the Academy of Art University in May — that color comes from human blood. The project is in experimentation phase now, with eventual plans to invite others to sit for a series of portraits, each subject contributing their own blood to tint their image.

It's worth noting that Deemy is well-versed in the safe handling of human blood — when he's not working on schooling or art, his full-time job is lab technician at a local blood plasma bank.

"It's fitting because it was decent training for working in a darkroom — I have the lab rules ingrained into my head now," he remarks.

Deemy's darkroom, above a billiard room and a marijuana dispensary on East Sprague in Spokane Valley is the size of a closet, but the kitchenette space at Hatch: Creative Business Incubator is ideal for his needs. There's a small stainless-steel sink, crucial for any darkroom, and the building owner let him paint the walls an inky black to prevent light pollution during film development. Rows of chemical emulsions in brown glass bottles and little boxes of powdered substances are neatly organized in a cabinet above the sink.

"I've been so buried in [the photographic] process, I didn't need a studio space to do things," Deemy says. "A lot of my work here has been learning these processes, which typically involves shooting something small up close to create the negative."

U

sing his tiny darkroom and a collection of antique and vintage cameras dating from 1894 to the 1940s and '50s, Deemy has printed his photographic negatives using a range of early and traditional processes, including tintypes and cyanotypes. Tintypes are created by making a direct positive, rather than a negative.

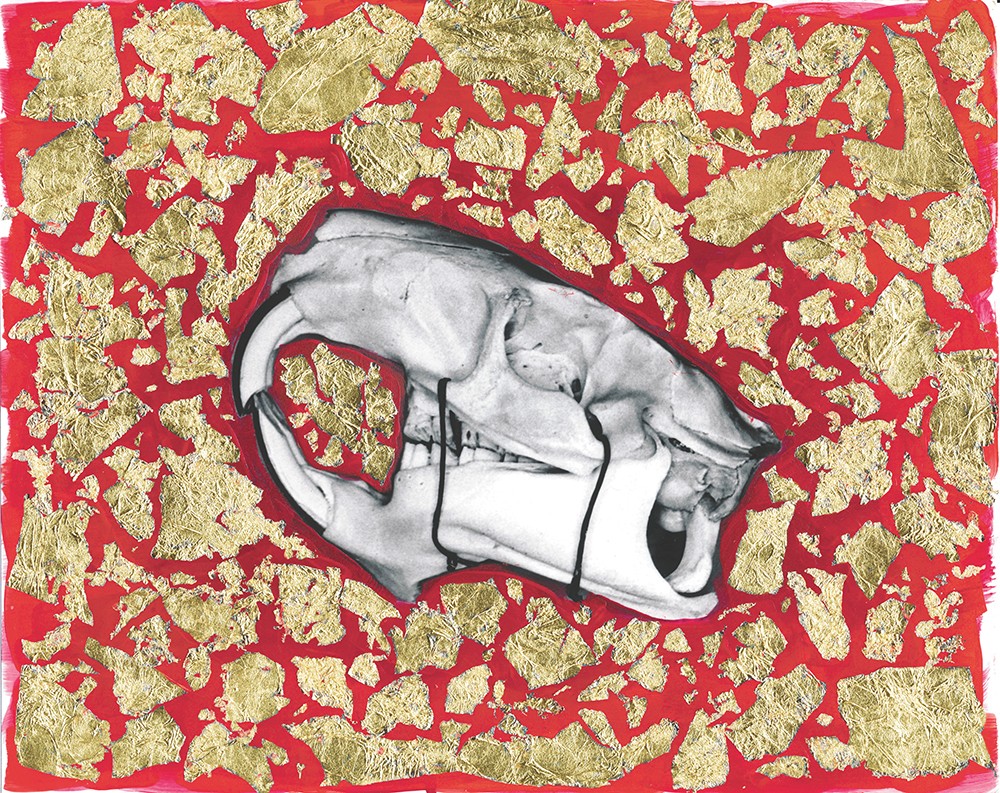

"Memento Mori," a series of Deemy's tintypes — a skeleton-themed commentary on death that took more than a year to produce — went on display at Giant Nerd Books on North Monroe last September and has been his most successful showing in Spokane so far. Some his pieces are still hanging there.

Deemy's interest in art, which stretches throughout his life, began with drawing and painting. Before he and his wife moved from Southern California to Spokane (she got a scholarship to attend Gonzaga about two and a half years ago), the artist had never worked in non-digital photography.

"We moved here and I didn't know the area, and I moved to a house with a decent basement, so I decided to teach myself how to work in a darkroom. I spent the first year shut off from the world diving into books and the Internet, teaching myself the history of these processes and the chemistry," he says.

Aside from the Giant Nerd Books show, Deemy has shown his work at the Brickwall Photographic Gallery, where he interned, and organized a fine art photography show at Hatch. He hopes to display an entire new body of work locally in the coming months.

"I'm definitely always working on something new, and I always feel like I'm not getting enough done because of the time I devote to work and school," he laments. "You work on one project long enough and by the time you're almost done, you have a whole new batch of ideas. There's this compulsion in working." ♦

See more of the artist's work at briandeemy.com, and on Instagram @brian_deemy