Jess Roskelley had one last mountain to climb before he could go home.

The challenge this time? Howse Peak, a massive vertical rock looming over a frozen alpine lake in the Canadian Rockies. Few even attempt the route to the top that Jess's group would try the next day, and only one group had actually done it, though it took several days and nearly cost them their lives.

Jess, accompanied by Austrians David Lama and Hansjörg Auer, planned to summit Howse Peak in a day.

Even getting to the base of the mountain required more exertion than the average person could handle. They skied over the frozen lake for hours before trudging through the snow to set up base camp beneath the towering peak. Jess, the 36-year-old from Spokane, had been climbing with David and Hansjörg on various peaks for weeks. Jess wasn't used to climbing with people as fast as they were, and he was eager to prove he could keep up. At the same time, he couldn't shake the sense that something bad was going to happen.

By Monday afternoon, April 15, they squeezed into a tent and prepared for a frigid night before an early start the next day. Jess, thinking of his wife Allison, dug out his GPS device, which could send texts from the most remote locations in the world.

At 2:30 pm, he wrote: "Hi love we are at camp so we have tomorrow and we're done I love you!"

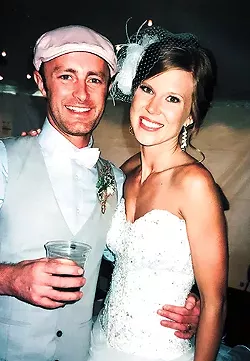

Jess texted Allison every night when he was on a climb. Whenever he'd be away for several weeks, he'd order flowers to be delivered each week he was gone. Allison and Jess were set up on a date by Jess's sister, and the two fell for each other hard. They got engaged within eight months. Nearly four years after their wedding, everything felt like it was coming together for Jess. He'd accomplished some of his best climbs, gaining enough notoriety that he was sponsored by the North Face — as good as it gets for a climber like him. He climbed to be the best, to push the limits of what he could do. But now he also climbed, in part, for Allison. If he could get through this one climb, he'd be one step closer to quitting his day job and climbing full-time. And if he could make enough money climbing, he could ease up a bit in a few years. He and Allison could have kids, maybe find a new house in Spokane with some property. They could grow old together.

Allison texted him back quickly. "Yay! I love you! I took dogs to get groomed in the new Jeep!" Jess again said he loved her and that after this he'd be done, this time ending the message with a smiley face.

"Ok I will turn this off and not waste any battery. I love you," Jess wrote, "and I'll update you tomorrow."

But Allison never heard from him Tuesday. Unable to sleep that night, she sent text after text after text. Wednesday morning, Jess's father John Roskelley, a famed mountaineer, called Parks Canada to report that the climbers failed to check in.

Days later, the bodies of all three men were found buried beneath the snow.

It's June, nearly two months since the accident, and John Roskelley is fighting through the avalanche debris on the mountain that killed his son.

John, who summited countless mountains in his day, isn't here to climb. He's retracing Jess's steps, searching for evidence. The bodies have been recovered, but much of their gear was left behind. John wants to retrieve it before the snow melts and treasure hunters get their hands on it. More than that, John wants his boots on the ground. It's what he knows how to do. And he needs to do it alone.

"I don't think being with people when I'm hunting down stuff for my boy or the other boys would do me any good," John says.

He's stoic when talking about Jess. John, 70, has dealt with the dangers of climbing his entire life. Throughout the '60s, '70s and '80s, John rose to prominence for pioneering first ascents or new routes on some of the highest and most perilous peaks in the world. He's keenly aware how things can quickly go wrong, and he's lost climbing partners over the years. But nothing, John says, compares to the love he has for his kids. Lately, his despair has manifest itself as pragmatism. Since April, John has spent months gathering evidence, analyzing photos and tracking GPS coordinates. He's made it his mission to find out exactly what happened at the top of Howse Peak.

John never encouraged Jess to become a climber, but inevitably climbing was a big part of the family. By the time Jess was born in 1982, John was doing monthlong expeditions — short for his standards — and coming home with T-shirts and souvenirs for Jess. At 14 months old, Jess shook hands with India Prime Minister Indira Gandhi during a visit where John was speaking at a mountaineering conference. Dinners at the Roskelley house often brought in legends of the climbing community, like Sir Edmund Hillary, who made the first successful summit of Mount Everest.

But as a child, Jess had other interests. Jess dreamed of becoming a Navy SEAL, a dream that died when he was thrown from a raft and nearly drowned, John says. While sometimes school was a challenge for Jess — largely due to his attention deficit disorder — Jess excelled in sports. He was passionate about racing bikes, but he tried out other individual sports like wrestling, track and karate.

Climbing was a bonding experience between John and Jess, as it might be for any Pacific Northwest, outdoorsy family. Except instead of going for a day to hike Mount Spokane, John would take Jess to climb Mount Rainier in a day. When Jess was a teenager, John took him to India and the two of them climbed Stok Kangri, a more than 20,000-foot peak.

"I just needed somebody to go with," John says wryly. "He was the logical victim."

At 18, Jess became the youngest-ever guide at Mount Rainier. But going up the same mountain all the time started to feel like a job, and John says Jess found real enjoyment while climbing other peaks with friends. Two years later, Jess asked his dad if he could come along for a climb of Mount Everest. John had attempted to summit Everest four times from 1981-1992 with no oxygen and with no sherpas, but couldn't quite make it to the top. John, at the time a Spokane County commissioner, told Jess no. That changed when one of the men John planned to go with, Ed Homer, was struck and killed by a rock on Mount Rainier. John called Jess, then a student at the University of Montana, and asked if he still wanted to go.

"You're going to have to miss the semester," John warned. "Jess said, 'Yeah, let's do it.'"

This time, they used oxygen and went with sherpas. And John, finally, made his Everest summit. Jess, at 20, was the youngest ever to do so at the time. Jess, however, wasn't interested in repeating Everest. He didn't want to do the expedition-style climbs like his dad. Jess wanted to be an alpine climber, with more technical climbs carving new routes up vertical faces on smaller peaks. Those routes often require even more skill than Everest, without having to endure the altitude of a giant mountain. Howse Peak, with an elevation of 10,810 feet, certainly was a prime candidate.

But in June, his dad is scouring through the snow looking for gear his son left behind.

Scattered throughout avalanche debris at the bottom of the rock wall near where the three climbers began their ascent, John finds some. There are gloves. Sleeping bags. Mats. A tent. Skis. A cookset.

Some of it is Jess's. Later, on a glacier near the avalanche that killed them, John finds his GPS device, the one he used to text Allison. John thinks it was with Jess on the climb. Maybe, John thinks, it can provide some answers. He takes what he can, and leaves the rest for the next trip.

He hikes back to the car, and gets back on the road. The drive is difficult for him, he admits. Each mountain emerging around a bend in the road was like a monument to a climb John and Jess did together years ago. He tries to temper his emotions.

"It's not an easy thing, to just ignore it," John says.

At 5:49 am on April 16, one of the climbers takes a photo of the vertical face of Howse Peak. Jess, Hansjörg Auer and David Lama are just leaving their tent and trekking up the steep slope. It's a clear day, just a few wispy clouds stubbornly hovering over nearby mountain peaks.

If the goal was simply to reach the top, there were certainly easier ways to go. Routes up the north and northeast face of the mountain have been climbed many times. John Roskelley, in fact, made it up one of those routes in 1971. But the east face? That's a "different animal altogether," he says. It's thousands of feet straight up a slippery rock wall or strips of snow and ice. And those long strips of ice form "some of the biggest challenges to the modern ice climber," says alpinist Barry Blanchard.

Blanchard was part of the first ever successful climb up the east face in 1999 with Steve House and Scott Backes. It took them several days, as they got caught in a two-day storm on their way up. They made it out alive, somehow, though Blanchard did suffer a broken leg when snow above him collapsed and swung him off and back into the mountain. House, in an Instagram post, wrote that Howse Peak was "the truest testing place of the most powerful men on their very best days."

They called their route up the mountain M-16, due to always feeling "under the gun." When Jess, Hansjörg and David began their climb, nobody else had climbed it since 1999. And climbing it in one day, like Jess and his companions planned? That would be an achievement even Blanchard would have a hard time believing.

But if any group of climbers could do it, it was these three. Calling them the "top climbers in the world" doesn't fully explain their prowess. Hundreds could make that claim. Those three climbers climbing up Howse Peak in April were in their prime, in a class of their own.

"They would be in the top 20," Blanchard says.

Jess, Hansjörg and David zoom up the mountain, on track to accomplish their goal in good time. Jess briefly stops to take two more photos, just before 9 am. One shows Hansjörg below, knee-deep in heavy snow, giving a thumbs up. The other shows David to Jess's left, his waist submerged in bright white powder as he looks toward the camera and smiles. As he does so, a few crumbs of snow gently trickle down the mountain.

In the years following Jess's famous summit of Mount Everest, climbing started to really become his passion.

Everyday life, meanwhile, became a real challenge. As a welder in Alaska, he'd work two weeks, then have two weeks off when he'd come back to Spokane or go climbing, building a list of impressive summits. Eventually he became a welding inspector, letting him quit his job and giving him even more time for the mountains. Other climbers started to take notice of his talents.

Scott Coldiron first met Jess around this period of his life, about nine years ago.

"He was kind of a cocky kid," Coldiron says. "Jess was really humorous and flippant ... My first impression was I didn't really like this guy."

Still, they soon became close friends, hanging around town in Spokane and climbing together. If Jess had a distinct climbing style, it was that he was precise and methodical. It went back to something John would always tell him: Strive for longevity, not fame in dying young. Coldiron also says when it got a little bit scary on the mountain, Jess remained cool and collected.

"But he was really funny — that was the main reason why you climbed with Jess. I would always have a good time climbing with Jess," Coldiron says.

In late 2013, Jess's sister Jordan set him up on a date with Allison, the woman he'd marry. She, too, was drawn to his sense of humor.

"He thinks he's really funny, which is even funnier because he'll say something and you're like, 'That wasn't really funny.' But he just laughs his ass off," Allison says. "And I just love that about him."

Jess's motivations to keep climbing, to keep challenging himself with more difficult ascents, were complicated. What was clear, however, is that climbing seemed to balance out his life.

"He always kind of struggled with the nuances of everyday, normal life," Allison says. "He'd never be a guy who sat in an office all day. Escaping to the mountains provided a sort of order to the chaos. And once he got into it, he wanted to carve out his own path — a path away from the shadow of his father."

Jess's younger sister, Jordan, says even though Jess always acted sure of himself, he held deep insecurities. Mediocrity, she says, was never an option in the Roskelley household.

"The Jess that I knew was very much worried that he was living up to his potential," she says. "He was confident in the mountains, but he was always worried about if he was doing enough to be the best person he could be."

In 2017, Jess sent waves across the climbing community when he and his partner Clint Helander established a new route along the never-before-climbed South Ridge of Alaska's Mount Huntington. It was a stunning achievement, and one that helped secure a sponsorship from the North Face. Earning that sponsorship, says his mother Joyce, was "absolutely the pinnacle of achievement in his life." He was at the top of his sport. It put him in a position where he could soon quit his job and make all his money following his passion.

Being sponsored by the North Face, though, came with responsibilities. It wasn't just having an active Instagram — Jess didn't care much about that. It also meant testing new gear. That's what brought him, David and Hansjörg together. They set out for the Canadian Rockies in April, trying out some lightweight climbing gear and summiting some extremely difficult peaks while they were at it.

For Jess, it was another chance to prove himself. That top 20 list of alpine climbers some would consider Jess part of? These guys were at the top. He couldn't wait to get out on the mountains with them. But he had to adjust to their style. They did more soloing than Jess usually did, meaning climbing without a rope, and they climbed as light as possible. John remembers Jess feeling a bit uncomfortable with the amount of solo work they did on the first climb together.

"Jess was definitely wondering, 'Can I keep up with these guys?'" John says.

On Sunday night, April 14, Jess called Coldiron. They talked on the phone for an hour. Coldiron says Jess was feeling stressed about the climb. They'd been pushing the limits for weeks, and Jess feared it might catch up to them."

"Jess didn't want to die climbing," Coldiron says.

Just before 1 pm, Jess, David and Hansjörg reach the summit of Howse Peak. They did it ridiculously fast. Relieved and slightly exhausted, with the cold wind blowing a faint mist in the air, they huddle together and smile for a summit photo.

In his home office months later, John studies that particular photo. Then John moves to the next one on his computer screen. He's collected dozens of pictures taken by the three climbers during their climb. Using the GPS coordinates of those photos, he pinpoints exactly where they were when each photo was taken using Google Earth.

This is what he knows: They began going up the M-16 route. But about halfway through, they veered off and traversed over a mixed ice and rock slope, toward a snow basin to the south that was slightly less steep than the vertical rock they'd been climbing. That snow basin is close to where the three of them had their legs submerged in soft snow. But it's also risky: John says those snow basins are something you typically don't want to get into.

"I'm just really surprised that the guys went into it," John says. "They must have thought that the snow conditions were pretty good."

It worked out, on the way up. They lifted themselves to the summit. They had a bite to eat. They didn't stay too long, and they started going back down.

The last photo taken, at 1:25 pm, showed them rappel down into the area where they exited the snow basin on the way up. It suggests they planned to go back down the same way.

At some point after that, an avalanche swept them thousands of feet down the mountain, killing them.

Their bodies were found in avalanche debris at the base of the east face, below that snow basin. According to Parks Canada, the climbers were not roped together, though it likely wouldn't have mattered given the avalanche's power. The ropes were configured in a way suggesting they were setting up to rappel down.

Allison was a mess when she didn't get a text from Jess. The next day, on Wednesday, officials spotted one body amid avalanche debris, but weather conditions prevented any recovery effort. At that point, John knew his son was gone, but Allison held out hope that, somehow, Jess survived.

The family went up to Canmore, Alberta. They initially stayed in the Airbnb the three guys had stayed in before the climb. The beds were unmade, their gear strewn throughout the house. Allison stayed up sobbing through the night. Reporters were constantly calling them.

Finally, on April 21, their bodies were recovered. Afterward, Jordan saw her brother's body. His helmet was crushed, which was a small comfort. It meant he didn't suffer.

Allison and Jess knew a day like this could come. They talked about it frequently. Last year, when a climber they knew died, Allison told him, "I don't know what I would do if this happened to you.

"And I remember Jess looking at me and saying, "Alli, this is always a possibility. I always take calculated risks — my first priority is to come home to you, but you have to accept some of these risks I can't control.'"

As much as Allison fell in love with Jess's sense of humor, she also fell in love with his ambition to climb. He inspired her. Taking that away, even though it could have prevented a tragedy, would have made him miserable.

Knowing it could kill him, however, doesn't make it any easier when it does happen. She says she handles her grief with checkpoints. Getting out of bed is the first checkpoint. Eating breakfast is the second. Getting back home and taking care of the dogs is another. Then it's going back to work.

She tries to remember what Jess said about the possibility of him dying: She has to move on. But then reality hits all over again when she has to go through his clothes, or when it's their anniversary, or when she hears a song he liked. Then another checkpoint: Selling his gear. It fills a shed in their backyard, where they installed a climbing wall for practice.

Walking in the gear room immediately upsets her.

"It's totally hard," she says, beginning to tear up as she looks toward the shelves. "Because, I mean, his boots are right there."

Today, she holds onto the voicemails Jess sent her from his trips, just to remember his voice. She saved them knowing they could someday be the only way to hear him. Her favorite is from when Jess called from Mount Huntington, just to say he loved her and was proud of her.

"He always said how proud of me he was — and he's in the middle of one of the hardest climbs in his life," she says.

She replays the silliest videos of him saved on her phone. There's Jess rocking out to music in the car. Then, of course, his favorite thing to do: Taking someone's beer and farting in it.

"He's just a jokester," she laughs. "Very inappropriate."

If you ask a climber what drives them, why they keep going knowing it could kill them, they usually won't be able to put their finger on it. It could be the adrenaline. It could be the competition. It could be the feeling of conquering nature.

For John, it's like doing a giant puzzle. Your fingers, your toes, your tools all have to be in the right place to do one thing: Make it to the top. And once you're at the top of the mountain, nothing else compares.

It's why John, Allison and the rest of Jess's family keep coming back to that summit photo. For everything else, Jess made it to the top.

"Jess is beaming because he kept up with these Austrian flying gods. I could tell right away that this was one of the happiest days of Jess's life," John says. "So that's what I need to focus on." ♦

This story has been updated to correct the timeline of Allison and Jess Roskelley's engagement and marriage.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wilson Criscione, born and raised in Spokane, joined the Inlander as a staff writer in 2016 and primarily writes about schools and social services. He can be reached via email at wilsonc@inlander.com or at 325-0634 ext. 282.