Andy Warhol and Polaroid imagery have a lot in common: both have withstood the test of time and trends to become not just iconic, but significant contributors to how we have evolved — Facebook, Snapchat, Google image search, Photoshop, etc. — as a culture of image consumers and makers.

Before there was Instagram, there was Polaroid itself. Instant cameras, which the company began producing in the 1940s, hit their stride in the '70s when Polaroid released the SX-70.

Unfolding like the head of robot #5 in the movie Short Circuit, the Polaroid SX-70 camera was a gateway to instant gratification in images, without which social media would not exist. With the click of a button (and a distinctive buzz-whirring sound) the SX-70 produced a single, plastic frame which almost instantly, and seemingly miraculously, materialized into a recognizable image. No more second-guessing about the viability of an image until it was processed, printed and developed; images could be made, viewed, commented on and even discarded within moments.

For artists of the time, it opened vistas of exploration. Need to scout a location for a painting? Take a Polaroid. Playing around with a color composition? Take a Polaroid.

And then there were artists like Andy Warhol, the so-called father of Pop Art whose 1968 screenprint Campbell's Soup Cans turned the art world on its ear in its blatant commercialism and glorification of the mundane.

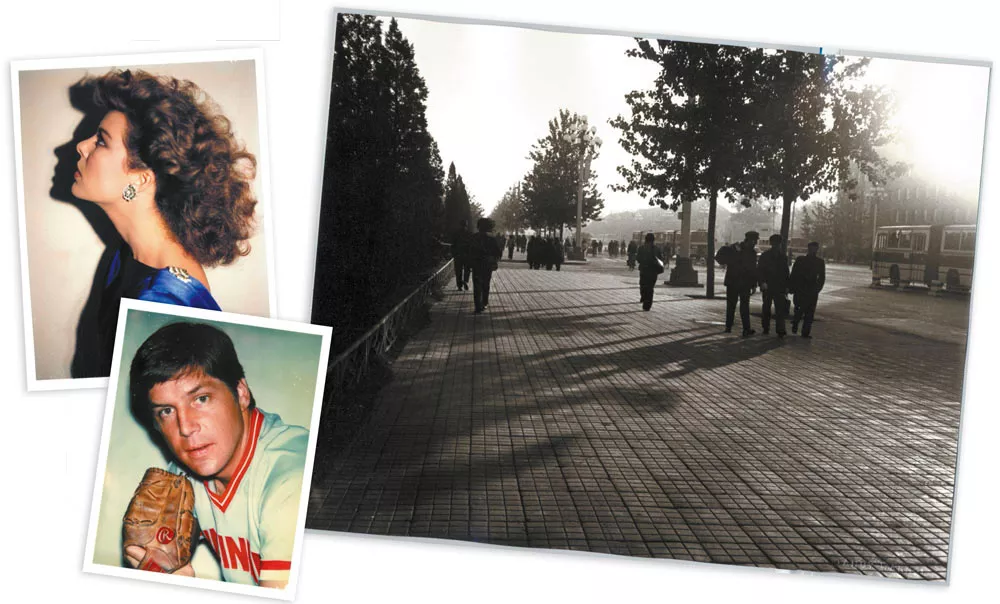

In Warhol's hands, Polaroid instant cameras became a means to an end, an essential tool for creating other artwork — drawings, paintings, and especially screenprints. For example, Warhol photographed well-known sports figures, including Olympic ice skater Dorothy Hamill and baseball legend Tom Seaver, to help prepare for a painting commission called the Athletes Series.

Warhol's images are now on view in "Andy Warhol: Photographs," a new exhibit at Gonzaga's Jundt Art Museum. The exhibition draws from the university's permanent collection, which received a curated selection of both Warhol Polaroids and black-and-white prints as part of the Warhol Foundation's 20th anniversary.

"Warhol's art is accessible," says Jundt director and curator Paul Manoguerra. "His subject matter is everyday life and scenes and people, our shared visual and material culture. I think that partially accounts for his continued popularity."

Manoguerra will give a free public walk-through Friday, May 30, in the Jundt Galleries, where seven additional Warhol works — prints acquired through the Warhol Foundation — also will be on display.

Throughout the '70s and '80s, Warhol took thousands of Polaroids, according to the Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, an organization whose efforts include the Andy Warhol Photographic Legacy Program. He favored the SX-70 and the Big Shot camera, which retailed for $19.95 when it was introduced in 1971 and became Warhol's preferred portrait camera.

Many of Warhol's images were of celebrities, but many were just average Joes about whom Warhol found something compelling.

"I've never met a person I couldn't call a beauty," Warhol is quoted as saying in his 1975 book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol.

Occasionally, Warhol would take a Polaroid of someone or something, then turn around and photograph the same thing slightly differently in black and white, an ephemeral contrast to the tightly cropped, harshly lit, color-saturated Polaroid.

Shot with a pocket-sized 35mm Minox camera, Warhol's images were not so much poetry as a visual diary, replacing his reliance on a voice recorder to document his day-to-day. Kids flying their kite in a New York City park. The airport terminal from inside a darkened car window. A street scene in China.

An almost compulsive desire to document, combined with quirky irreverence, is part of what makes Warhol so relevant to today's media-intensive audiences. ♦

Andy Warhol: Photographs • Through Aug. 9 • Gonzaga University, Jundt Art Museum • Free public walk-through Friday, May 30, at 10:30 am • www.gonzaga.edu/jundt • 313-6613