It's Independence Day, 1927 — six weeks after aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh has completed the world's first transatlantic solo flight, and three months before the premiere of The Jazz Singer, Hollywood's first feature-length "talking" film. Revelers have gathered along the beaches and docks in the town of Coeur d'Alene, having made the pilgrimage to its Fourth of July celebration, an annual highlight throughout the Inland Northwest. At some point during the festivities, a huge stern-wheel steamboat is towed out onto the water and set alight. She is the Georgie Oakes, erstwhile queen of Lake Coeur d'Alene.

The flames rise up, burning brighter and more intensely than any fireworks display. They quickly consume the wooden decks that once held freight, soldiers, miners, loggers, homesteaders and sightseers at various stages throughout her 35-year career spent plying this nexus of lakes and rivers. But it isn't the glorious Viking funeral that guides will recount through nostalgia's haze some 90 years hence. The blazing vessel soon drifts too close to valuable storage docks, and the fire is extinguished before it's able to complete this act of nautical cremation. For weeks afterward, the charred wreck of the Georgie Oakes will struggle to remain afloat until at last she yields to her injuries and slips beneath the lake's surface.

Nearly 50 years of steamboating history on Lake Coeur d'Alene were brought to a close as the remnants of Georgie Oakes sank. Although it would be more than a decade before the prestigious Flyer, a sleek excursion steamer, met the same pyrotechnic end, by the early 1920s the steamboat's primacy in regional transportation was already in irreversible decline. The automobile would deal the finishing blow to any rugged vestige that survived the Great Depression.

During that tumultuous half-century, however, steamboating shaped expansion in the region. Steamboats were present almost from the moment Coeur d'Alene mustered enough bravado to declare itself a town. Traversing the second-largest lake in Idaho and its network of navigable waterways along three rivers — the St. Joe, Coeur d'Alene and Spokane — steamers opened transportation routes that were all but unreachable by rail or without considerable difficulty by foot. They determined areas of settlement, making now-forgotten Idaho villages like Stinson, Black Rock, Omega Landing, St. Joe City and Ferrell into colorful centers of recreation and commerce, albeit fleetingly. And they allowed our fortune hunters to relieve the region of its natural resources — chief among them timber, lead and silver — while delivering ever more farmers and homesteaders further into its forested interior.

Although steamboats were powered by the area's vast supply of cordwood, their existence was always at the mercy of the prevailing socioeconomic winds. On Lake Coeur d'Alene, they morphed from supply transports when the town was little more than a glorified garrison, into ore haulers during the mining boom, into shuttles for laborers and goods during the timber harvests, and finally into pleasure boats for throngs of day-trippers. At the height of all this activity, Lake Coeur d'Alene was home to more than 50 steamboats and the site of more steamboat traffic than any lake west of the Great Lakes.

The Military Period (1880-83)

Steamboating on Lake Coeur d'Alene had its origins in the construction of the Mullan Road. Starting in the spring of 1859, Lt. John Mullan and his team of more than 200 U.S. Army troops, engineers, workmen and surveyors began work on the 611-mile overland route designed to connect Fort Benton, Montana (Dakota Territory at the time), which lay at the head of the Missouri River and linked to important ports eastward, to Fort Walla Walla, located in Washington Territory not far from the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers. Nearly two decades earlier, Jesuit missionary Father Pierre Jean DeSmet followed a similar path and described the difficulties it presented to would-be travelers:

Imagine thick, untrodden forests, strewn with thousands of trees thrown down by age and storms in every direction; where the path is scarcely visible, and is obstructed by barricades, which the horses are constantly compelled to leap, and which always endanger the riders.

Completed in 1862, the Mullan Road primarily conveyed wagons and pioneers, but its occasional military traffic would have a lasting impact. In 1877, General William Tecumseh Sherman — he of controversial Civil War scorched-earth tactics — camped with a detail near Lake Coeur d'Alene and was inspired by the site's natural splendor to suggest it for a fort. Within a year, the Army had established Camp Coeur d'Alene at the point of land where the Spokane River flows from the lake. The military presence was intended not only to quiet growing unrest among Native Americans whose tribal land was gradually being usurped, but also to protect crews who were busy laying communication and transportation infrastructure so essential to Manifest Destiny. The camp officially became a fort (renamed Fort Sherman several years later) in April of 1879.

It was in that same year that the post commander, Lt. Colonel Henry Clay Merriam, commissioned the construction of the very first steamboat on Lake Coeur d'Alene in the event that the Mullan Road's unreliable supply lines were ever disrupted. The stern-wheeler was to be 85 feet long with a 14-foot beam, capable not only of regularly transporting supplies but also, in emergencies, soldiers. Its cost was $5,000. Captain Peter C. Sorensen, a 46-year-old Norwegian immigrant then based in Portland, Oregon, was summoned to oversee construction, which, according to contemporary accounts, went as smoothly as one might expect of any untried major project undertaken in frontier wilderness.

"Sorensen actually disassembled an engine and brought it by boat and by wagon to be used in the first steamboat," says Robert Singletary, an authority on Coeur d'Alene history who frequently gives talks and walking tours in Sorensen-inspired costume and character. "He had problems getting that engine to fit the structure, so that was a bit of a struggle."

When the vessel was finally given its delayed launch late in 1880, Sorensen christened her the Amelia Wheaton after the daughter of the new post commander, Colonel Frank Wheaton. Sorensen never went back to Portland, instead putting down roots not far from what was little more than a tent city at the time, and became the ship's captain. Over the next three years he steamed across the lake in the Amelia Wheaton, mostly ferrying hay and grain for the fort's cavalry mules.

As a civic leader and master shipbuilder, Sorensen's presence would loom large over Idaho steamboating until his death on Jan. 16, 1918. On those sleepy trips piloting the Amelia Wheaton or his own Lottie back and forth on the lake, he found ample time to bestow names, still in use today, upon natural features, among them Cougar Bay, Black Rock Bay, Echo Bay, Beauty Bay and Powderhorn Bay. Sorensen built his home on the bluff above Kidd Island (he named the spot North Cape) and acquired a reputation as a tinkerer and inventor. He built an automated contraption to tend his chickens while he was underway and maintained a large telegraph apparatus of his own. Sorensen's great-grandson said that he was the one responsible for building an eight-foot musical cube out of glass bottles on Kidd Island along with other "scientific displays," as well as a not-so-scientific painted wooden monster that floated on the lake. Singletary cautions against accepting tales of Sorensen's wilder experiments too readily: "You have to take that with a grain of salt. I haven't been able to verify any of that outside of his expertise in shipbuilding."

That expertise is well documented. Sorensen, along with his gifted shipbuilding partner Peter Johnson, was behind more than half of the boats on the lake, including the General Sherman, Volunteer, Schley and Torpedo. He constructed his last boat, North Star, in 1907, by which time he was well into his 70s.

The Ore Period (1883-95)

A. J. Prichard's discovery of gold in the Coeur d'Alene district in 1881 and the mercenary scramble that followed in 1883 had an effect that would be repeated as long as steamboats plied the lake. The Amelia Wheaton, which had hauled fodder until that point, soon became a shuttle for starry-eyed prospectors who dreamt of striking the next motherlode. Steaming roughly 20 miles across Lake Coeur d'Alene and then 30 miles up the Coeur d'Alene River, the Amelia Wheaton deposited passengers at the Old Mission, where, depending on their wherewithal, they could travel by foot or by horse to Prichard Creek Valley, now known as Murray, Idaho. This water route had the advantage of bypassing a good portion of the overland journey via the Mullan Road. Tens of thousands of miners, settlers, speculators, claim-jumpers and other assorted fortune hunters flooded into the area. More frenzy ensued when abundant silver veins were discovered in 1884, giving the valley the name that stands today.

Regional historian Ruby El Hult, who grew up near Harrison watching steamers chug by, explains in her book Steamboats in the Timber (1952) how railroads and steamboats indirectly began to work in tandem at the start of the gold rush:

The Northern Pacific Railroad Company was partly responsible for the magnitude this first wild stampede attained. The railroad had been built through this undeveloped country in 1881-83 at colossal expense, and the railroad officials eagerly seized upon the news of the mining strike as a means of stimulating travel over the line. They put out glowing, exaggerated pamphlets which lured people from all over the country to come to Idaho.

The Northern Pacific's consecutive rail stops of Rathdrum and Spokane benefited from this massive and spontaneous influx, and so did the steamboat landing at Coeur d'Alene. To accommodate the crowds arriving by stagecoach in the still-unincorporated settlement, hotels, restaurants, saloons, warehouses, wharves and, yes, more steamboats were quickly built. One was the stern-wheeler Coeur d'Alene, with a length of 120 feet and a 14-foot beam. The other was Sorensen's smaller, propeller-driven General Sherman. Launched in 1884, the two vessels established another defining trait of the steamboat era, namely, fierce competition in which monopolistic control was seen as the only desirable outcome. They engaged in fare wars so cutthroat as to be comical until the General Sherman's owners struck a deal that allowed their ship — and only their ship — to be resupplied from the piles of cordwood chopped, stacked and sold by Native Americans along the waterways. Without fuel to stoke its boilers, the Coeur d'Alene had to concede defeat.

Daniel Chase (D.C.) Corbin arrived in Rathdrum around this time. No sooner had he alighted from the train than he began to envision an interlinked regional feeder network that would help the mining interests part more easily with their precious metals. He proposed a standard-gauge spur that would branch off the Northern Pacific at Hauser Junction and lead to Lake Coeur d'Alene, where steamboats would bridge the watery expanse between that line and a narrow-gauge railroad into the mountains starting at the Old Mission.

Similar ideas had already occurred to other entrepreneurs, but Corbin, who compensated for a legendary lack of magnanimity with an excess of opportunism, was the first to put the necessary pieces in place. His lines were completed in 1886.

For the nautical leg, Corbin purchased the General Sherman as well as the Coeur d'Alene, making allies of the two former competitors. In 1887, he added the broad-shouldered Kootenai. According to Steamboats in the Timber, this was "a big, powerful boat" that "could break ten inches of ice and still make good time, and could plow through ice as thick as twenty-two inches."

Yet Corbin's calculating gaze soon drifted northward, and with customary prescience he sold the Coeur d'Alene Railway just two years later. He then concentrated on a series of lines to connect the mines of southeastern British Columbia to Spokane.

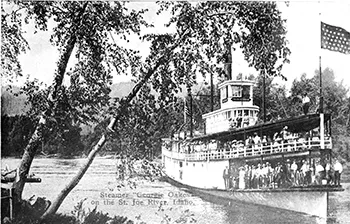

Between 1887-91, technological advances (and the installation of industrial mining machinery) led to exponentially more ore being extracted from the area's lead and silver mines. Combined yields rose from $800,000 in 1887, to $1.2 million in 1888, to $4 million in 1890 and up to $9 million in 1891. The ever-growing output taxed the small fleet of steamboats that hadn't been designed for hauling ore. The Coeur d'Alene, for example, was only able to haul 50 tons of ore, so its cabins and superstructure were removed and installed onto an impressive new hull built in 1891. This new ship measured 150 feet in length and 28 feet in beam. She could haul double the capacity and would immediately be put to work on the mining run. She was the famed Georgie Oakes, named for the daughter of the president of the Northern Pacific, which had purchased the line from Corbin in 1888.

The Timber Period (1895-1910)

Once the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company had finished constructing a direct route to the Coeur d'Alene mining region in 1890, it was no longer necessary or cost-effective to transport the ore downstream, and the role of steamboats was diminished — for that purpose, at least. In the waning years of the 19th century, the water routes once essential to the mining industry became the new thoroughfare for timber.

The expansive forests along the banks of the St. Joe, the St. Maries and the Coeur d'Alene rivers were rich with white and yellow pine, tamarack and fir. The St. Maries Valley alone boasted the largest stand of white pine in the world. This made the area especially attractive to timber barons, who had been clear-cutting the forests around the Great Lakes region and were now beginning to eye the virgin bounty that lay westward. El Hult notes that the fawning pleas of the local paper might have helped to draw their attention:

In 1893 the Coeur d'Alene Press said wistfully, "Mill men, why don't you come and take a look over this country? You are letting a good opportunity slip through your fingers. There are millions and millions of feet of timber in close proximity to this place, and this is a most advantageous location for a good mill."

The logging companies obliged, giddy over the prospect of 15 billion feet of densely packed timber that could be used to sustain the explosive growth occurring all over the country, particularly in the Inland Northwest and along the West Coast. Two years before the turn of the century, Idaho mills cut 65 million feet of lumber. A decade later, that number had increased almost eightfold. By 1910, Idaho was producing and distributing 745 million board feet each year, and new residents had swarmed into Coeur d'Alene, which saw its population climb to more than 7,000 that year.

William "Bill" Dollar was one of the first timbermen to arrive. He and his improbable name swaggered into town in 1899. In 1901 he was joined by Frederick A. Blackwell. Their respective corporations would go on to log 200 million and 1.25 billion of the nearly seven billion feet of timber cut from the region's precipitously steep hills by 1905. To achieve such staggering output, they relied on the backbreaking labor of loggers and millhands, who in turn relied on the steamboats to ferry them and their kit from Coeur d'Alene to points along the timber route — isolated outposts like Ramsdell, Silvertip Landing and Cosmo's Landing, or remote towns like Harrison, St. Maries, Ferrell and St. Joe City. Steamboats were these towns' only connection to the wider world. A Wild West atmosphere developed along the riverbanks, replete with gambling, drinking, prostitution, scam artists and shootouts. As the timber boom was largely responsible for conjuring these waterfront whistle-stops into existence, its eventual bust would cause many of them to shrink or disappear completely.

In 1902, the aptly named Boom Company began sorting the thousands of logs that were chuted down the steep hillsides into the St. Joe. Each was identified by a log mark, similar to a ranch's cattle brand, that identified which company had felled and claimed it. Steam-powered tugs would then tow the vast rafts of bound logs, or brails, to the appropriate mills near Coeur d'Alene. The painstaking journey could take two days or more. When the logs were destined for mills farther west in Post Falls, they would be released into Cougar Bay, where they would eddy like pools of giant matchsticks before being carefully fed into the mouth of the Spokane River.

If the logs filled the waterways too snugly, lumberjacks had to walk out over the floating terrain, plant dynamite into the logjam and blast the passage back open again. The job carried the constant risk of death.

Logging would continue at a brisk pace until the Great Fire of 1910, when the flint of an unusually hot, dry summer struck the steel of human carelessness and natural mishaps. Over two days in late August, the firestorm destroyed three million acres of timberland — equal to 7.5 billion board feet of timber — across Eastern Washington, North Idaho and Western Montana. A contemporary observer reported flames several hundred feet high, "fanned by a tornadic wind so violent that the flames flattened out ahead, swooping to earth in great darting curves, truly a veritable red demon from hell."

Lumber production in the 10 counties of North Idaho would slowly resume after the Big Blowup, reaching a zenith of 950 million board feet in 1926, the year before the Georgie Oakes was consigned to the lakebed. By 1932, output had fallen to 200 million board feet.

The Excursion Period (1900-1920)

A civil engineer and bon vivant named Joseph Clarence (J.C.) White had been summoned to Coeur d'Alene by D.C. Corbin back during the mining boom to help construct his narrow-gauge railroad. Once that was completed, for several years White lived and worked out of Spokane before returning to Idaho in 1892. There, much like every other businessman in the area, he became connected with the timber and transportation industries. And, much like every other businessman in the area, he watched with keen interest and no want of envy as boats steamed virtually unchallenged over the lake and rivers, making money hand over fist.

The 38-year-old White later secured $30,000 in backing from Bill Dollar and co-founded the Coeur d'Alene and St. Joe Transportation Company on Oct. 8, 1903. He contracted an outsider to build a 147-foot side-wheeler at a cost of $45,000. The new Idaho's size and 1,000-passenger capacity would give the noble Georgie Oakes a run for her money.

For the benefit of turn-of-the-century commuters and weekend excursionists, the Idaho's dockside arrivals and departures were scheduled to coincide with the new electric railroad running from Spokane to Coeur d'Alene. The Transportation Company's machine was so well-oiled that competitors couldn't keep pace and subsequently sold out to White and his partners in 1905. To humiliate the former owners even further, red bands proclaiming Transportation Company ownership were placed around the boats' smokestacks. The victor became known as the Red Collar Line and would officially change its name accordingly some years later.

With improved, modern service, the public developed a passion for excursions. Every Sunday, crowds of people — families, couples, bachelors, travelers, sightseers — would ride in to Coeur d'Alene on the electric line and catch a round-trip steamboat to idyllic St. Joe or rustic St. Maries. They would eat, sing, converse, carouse, court and dance as the boats glided close to 30 miles across Lake Coeur d'Alene and then up the St. Joe River, famed for its shadowy waters lined by pine and cottonwood. On the return journey, passengers could enjoy hearty suppers in the dining room, and the merrymakers who weren't already in their cups from a day spent picnicking or saloon-hopping could visit the onboard bar (that is, until the Volstead Act took effect in 1920) and hope to avoid staggering overboard before reaching the depot that evening.

The Red Collar Line enjoyed a heyday until the mid-1910s, when it came up against outside forces that were beyond even a monopoly's control. The rail lines had slowly expanded their reach, offering passengers more direct overland alternatives; in 1909, the Milwaukee Road, later known as the Route of the Hiawatha, opened along the south end of the lake, with trains running from the Great Lakes to Puget Sound through St. Maries and Plummer. And the gasoline-powered automobile, the pinnacle of individual convenience, was becoming more widespread. Not even the Spokane-to-Coeur d'Alene electric line had been able to hold out against it. In 1922, the Red Collar Line went into receivership after a few desperate and costly attempts to retain its former glory. A handful of steamboats would linger on the lake for a few more years.

Epilogue

Peppered with anecdotes about desperate rescue missions to save stranded passengers and full-throttle races between rival captains, the history of steamboating on Lake Coeur d'Alene and its tributaries is as deep as the lake itself. Some time should be taken in closing to recount the fates of several steamers, each of which took on a character all her own and became the centerpiece for stories that were passed along over the decades by passengers, captains and crew.

In 1888, the Amelia Wheaton was sold by the government to a private party. She steamed up and down the St. Joe until 1893, when part of her was transferred to a new hull and she was renamed the St. Joseph. Her old hull became a freight barge. The General Sherman was abandoned around 1891 and sank in shallow water before being raised and repaired in 1894. It too steamed the St. Joe for several years until its mechanicals were salvaged and installed into the new Schley in 1899. Its hull was towed out onto the lake and sunk. The Coeur d'Alene, having been partially refashioned into the Georgie Oakes, became a barge on which floating dances were held. In 1914, the pillaged hull of the Spokane was burned as part of the town's Fourth of July celebrations. After just 10 years of service, the palatial Idaho was retired and used as a massive floating shed for storing apples before it caught fire and sank in 1915.

There are a few steamboating relics still scattered around the Lake City. Just off the Kidd Island shore, below Captain Sorensen's old perch, is the rusting boiler of the St. Maries, salvaged by divers as scrap metal. A singed and weatherbeaten fragment of the Idaho's paddlewheel remains in front of the Museum of North Idaho, where you can see many more artifacts of the era. Next to it sits a huge propeller, which divers recovered from the Flyer years after the swift steamer was set alight — just like the old Georgie Oakes.

The Flyer's retirement was the last major event in the Coeur d'Alene steamboating era that Sorensen had helped to launch. On Feb. 4, 1938, in front of a crowd that had gathered on City Beach to bid her a final farewell, she was burned down to the waterline and slowly foundered, joining her illustrious predecessors in steamboating history. ♦