Young Tony Canadeo was an unlikely star on the Steinmetz High School football team on the north side of Chicago. Although just 5-foot-8 and 150 pounds, he was fast and had great football instincts — he played both offense and defense, and even punted and kicked field goals. He had a passion for football, and his appetite for playing only grew stronger. But in 1937 America, there was no recruiting the way we know it today — mostly just word of mouth and maybe an invite to try out for a college team.

As graduation approached, Canadeo thought about summer work. His older brother, Savior ("Savy") attended St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin. Savy found Tony a summer job in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where he met "Tiny" Cahoon, the De Pere High School football coach. Over that summer, Canadeo learned that Cahoon had played football for a school somewhere out West — Gonzaga University — and was a teammate of that team's current coach, Mike Pecarovich. Cahoon was a big Gonzaga supporter, and he did some of that word-of-mouth recruiting, encouraging many of his players to check out the Bulldogs. Eventually Canadeo decided to give Gonzaga a try.

So in late August 1937, Canadeo and his high school teammate Mo Solka headed to Spokane in a Packard. The trip opened Canadeo's eyes to the beautiful Western sights, from the foothills of the Dakotas through the mountains of Montana and Idaho.

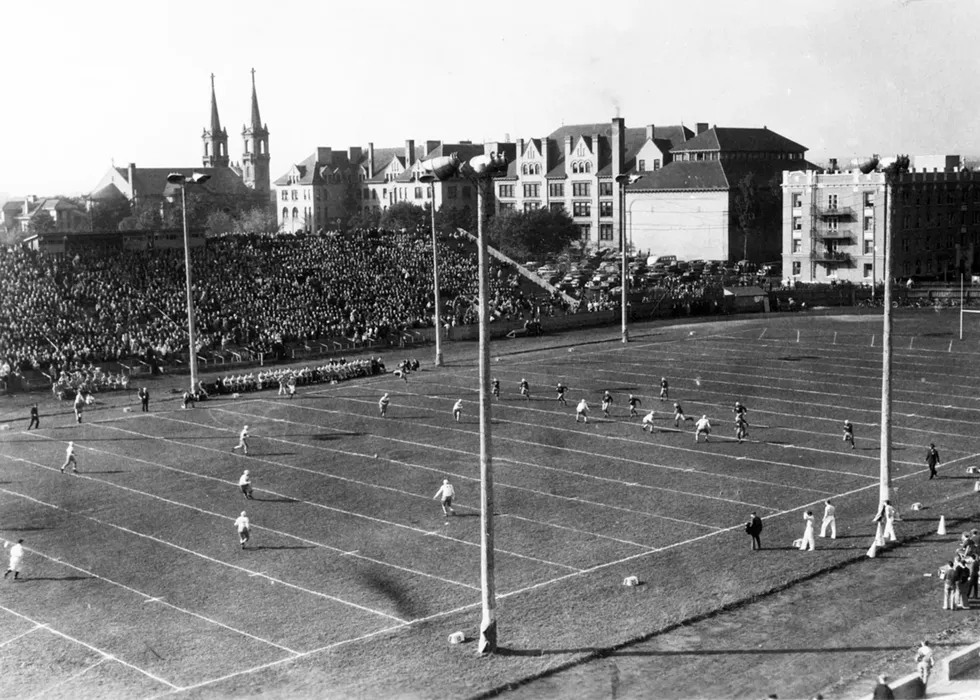

Six flat tires and seven days later, they arrived at Gonzaga, enthralled with the beauty of the campus and the city of Spokane. After checking into Desmet Hall, Canadeo was welcomed by the Jesuits and the faculty, and he visited the 13,000-seat football stadium. As he looked upon the impressive playing field, little did he or anyone know that this football field would provide the platform for the future stardom of an unknown Italian from Chicago. Canadeo would put Gonzaga athletics on the national map, and, eventually, ensure the future of the Green Bay Packers as one of the greatest franchises in all of football.

But in those days, first you had to make the team. As a freshman, there was no guarantee, and Canadeo was nervous, competing with 90 other athletes with the same dreams. But after two long TD kickoff returns in practice, he was quickly awarded a scholarship and a spot on the roster. He could keep his scholarship as long as he fulfilled the requirement that he work at the school for two weeks of every month.

The rest? He'd have to earn that himself.

THE LAND OF PROMISE

It all began on May 5, 1919, when "Little Tone" was born, the son of Anthony Sr. ("Big Tone") and Katherine Canadeo. With his parents' permission, "Big Tone" had left his home in southern Italy at age 13 with his uncle to immigrate to the U.S. — "the land of promise." Anthony grew up and eventually met Katie; they raised four boys and a girl in an ethnically diverse neighborhood in North Chicago. Anthony became a streetcar motorman, while Katie raised the family with a deep Catholic faith, work ethic and values that respected others. They were proud Italians who loved America.As "Little Tone" grew up, he played sandlot baseball and football and was an avid Cubs and Bears fan. With his buddies, he would sneak into Wrigley Field to watch his favorite teams play. His favorite players were Bronko Nagurski, a burly, bruising fullback who intimidated opposing players, and Beattie Feathers, a small, fast, shifty halfback who was the first NFL player to rush for over 1,000 yards — a feat unthinkable in an era of 11 games.

At Steinmetz High, Canadeo was popular and named team captain. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds flat and became a versatile, all-around great player. In his senior year, he led Steinmetz to the Chicago Sectional championship, falling just short of victory.

After leaving his family behind in Chicago and enrolling at Gonzaga, he first had to adjust to the Jesuit way, as the school was guided by the principles of the Ratio Studiorum, a set of rules outlined by the most prominent Jesuit educators. There was firm discipline, order and religious commitment to the moral objective of developing and strengthening character in their students to be gentlemen with good manners. Canadeo committed himself to this Christian education training and the Gonzaga goal of "preparing its sons for the battle of life... spiritually, mentally and socially." These principles would have a profound effect on Canadeo.

But Canadeo chose Gonzaga due to its rich and growing football history; some even called it "The Notre Dame of the West."

Gonzaga football was established in 1892 by Dr. Henry Luhn. A physician by trade, Luhn was Notre Dame's first football captain and GU's first-ever football coach. While recognized in 1988 with entry into Gonzaga's Hall of Fame, Luhn and Gonzaga football are all but forgotten today. In fact, most folks only know it existed from an ironic T-shirt that states, "Gonzaga Football: Undefeated since 1941."

After Luhn, Gus Dorais became head coach, serving from 1920-24. Dorais played for Notre Dame, and in 1918 was "co-coach" with Knute Rockne, who coached the lines while Dorais coached the backfields. In 1919, the "Fighting Irish" decided to name one head coach. A coin flip between the two best friends determined who it would be. Rockne won the toss. So Dorais, to the benefit of Gonzaga, moved West to become head coach.

In four seasons, Dorais produced outstanding teams with players like Houston Stockton, Ray Flaherty and Mike Pecarovich. Dorais' Bulldogs played in the 1922 East-West Bowl against West Virginia and were undefeated in 1924.

BIG ZAG ON CAMPUS

In 1937, freshmen were not allowed to play varsity, so Canadeo played under Coach Claude McGrath on the frosh team. Having filled out to 5-foot-10 and 175 pounds, he improved his speed, agility and skills, developing as a slashing halfback with sharp cuts, shifting gears and the natural ability to spin out of tackles. Those skills would serve him well in his varsity years and beyond into his professional career.Immediately, in his first varsity game as a sophomore, Canadeo made a powerful impression. Donning jersey No. 13, he scored four touchdowns, including a 55-yard sprint down the middle of the field. As a newcomer to college football, he quickly gained national attention with the "Outstanding Play of the Week" — a 105-yard kickoff return against rival Washington State, followed by another 102-yard return against Loyola the next week.

The fans and press went wild over his feats, but Canadeo humbly gave credit to his teammates, like Ray and Cecil Hare. One writer described Canadeo's runs as "a symphony in rhythm as he glides in easy, floating motion, changes pace quickly and smoothly, then bursts into speed in a step. He is dangerous from any place on the field."

That sophomore season, at the ripe old age of 20, Canadeo inherited an unusual characteristic when his hair started to turn gray. Sportswriters and teammates took notice and, combined with the elusive running that caused defenses to miss tackles, earned him the nickname "ghost." Consequently, the nickname evolved into "The Gray Ghost of Gonzaga."

Despite Canadeo's being named to the Liberty All Pacific Coast First team, Gonzaga finished 1-7, and Coach Pecarovich departed, to be replaced by Coach "Puggy" Hunton, a Gonzaga High School coach whose teams won seven city high school championships.

The year of 1939 was both ominous, as Germany invaded Poland, and exciting, with color movies like Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz hitting theaters. At Gonzaga, the combination of Coach Hunton and Tony Canadeo was about to produce its own kind of excitement.

Canadeo became the star of the team and one of the best on the West Coast. In their first two games of 1939, the Bulldogs suffered road losses to WSU and St. Mary's. Next, they traveled to Lubbock, Texas, to play powerful Texas Tech, which was favored by three touchdowns. Gonzaga won 6-0 with Canadeo throwing the lone touchdown pass.

As their train returned to the Great Northern Station in downtown Spokane, the student body, alumni and fans welcomed the team home as they swarmed the station. They yelled, screamed, snake danced and sang, with the pep band throbbing along in the background. As each player got off the train and walked to the awaiting bus, the passionate fans cheered and sang the school fight song and followed the team to Boone Avenue for more celebration.

During the following week, the team autographed the game ball and sent it to Gonzaga alumnus Bing Crosby, who was a huge supporter of Gonzaga football. The victory over Texas Tech was the turning point that season, as they won the next five in a row and outscored their opponents 94-7. The mighty Bulldogs traveled to Eugene and defeated an Oregon team (the Webfoots) with sights on the Rose Bowl, 12-7. Canadeo scored both touchdowns. Again, the team received a huge welcome in Spokane and were hauled into the Fox Theater where Coach Hunton and Canadeo were singled out on stage and received a standing ovation.

The next week, the Bulldogs traveled to Montana to defeat the Grizzlies 23-0. But just after leaving the field, Canadeo was informed, right in the locker room, that his father, 47-year-old "Big Tone," had died. He sobbed on the bench at his locker, devastated and heartbroken. His teammates lifted him up and put him on a direct flight from Missoula to Chicago for the funeral. Canadeo stayed with the family for a week as they all assessed how to take care of their mother, Katie. Together, they agreed that Canadeo should return to Gonzaga and finish his education while the siblings would all pitch in to support their mother.

The Bulldogs finished with a 6-2 record, and, along with being named an All American, Canadeo was recognized along with Joe DiMaggio and Ernie Lombardi as one of the outstanding Italian American athletes of 1939. In his senior year of 1940, he was again named to the All American team for small colleges, making it two years in a row. Many regarded him as the best halfback in the nation.

GREEN BAY CALLING

On May 21, 1941, 21-year-old Canadeo graduated with a philosophy degree, planning to eventually pursue a career in military aviation after adding a graduate coaching degree at Gonzaga. However, back in Green Bay, where that summer job played such a pivotal role, Curly Lambeau, the Green Bay Packers coach, had different plans. He made Canadeo the 77th overall pick in the 10-team NFL draft.Curly valued Canadeo's versatility and thought he would be a good complement to wide receiver Don Hutson. Lambeau, who co-founded the Packers in 1919, quickly created the NFL's strongest offensive passing team. When Canadeo joined Green Bay, the Packers (along with the Chicago Bears) dominated the NFL with, at one point, five championships in 12 years. Green Bay was often compared to "David" vs. Goliath, as the tiny town of 40,000 residents competed and more often defeated the big city teams of New York (7.5 million), Chicago (3.4 million) and Philadelphia (2.0 million).

From the first day that he met Lambeau to the day that Lambeau left the Packers in 1950, Canadeo had the utmost respect for Curly as his boss and a "hell of a coach." Lambeau gave him the No. 3 Navy blue jersey with gold pants (Notre Dame's colors).

Canadeo impressed immediately in Green Bay. In the 1941 season opener, he scored a touchdown, was the leading rusher and did all the punting in a 23-0 win over Detroit. By then 5-foot-11 and 190 pounds, Canadeo broke two bones in his left hand that day. That didn't stop him the following week, when he threw a TD pass to Hutson, ran for a touchdown and intercepted a pass against Cleveland in a 24-7 win.

Next came the Bears. The rivalry between the Packers and Bears was unlike any other. Both teams dominated in the same league. To say that the Packers got up for a game against the Bears was a gross understatement. Beating the Bears was like winning a separate championship.

On this given Sunday, 46,000 attended, and upon Canadeo's first time carrying the ball he remarked, "I came up spitting teeth."

The Bears won the game, but the Packers reciprocated in November at Wrigley Field, where Canadeo's Chicago friends all showed up to cheer and harass him from the stands. At the end of the season, the two teams were deadlocked at 10-1 and the Bears beat the Packers in a playoff game and went on to win the 1941 NFL championship over the New York Giants.

The end of the season was marked by the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and America's entry into World War II. This would change the nation in profound ways, as most of the young men of America dropped what they were doing and left home to serve in the armed forces. Football was no longer a priority.

People wonder what happened to football at Gonzaga University. World War II, that's what happened. Due to lack of players, support and funding, Gonzaga and other Jesuit universities ended their programs — and they never came back.

So 1941 remains football's final year at Gonzaga, but the sport planted seeds of athletic excellence at the school. Some 50 years later, those seeds sprouted again, this time across a wide spectrum of sports, most notably basketball.

As it was in Canadeo's times, Gonzaga athletics once again inspires awe across the American sports landscape.

A HALL-OF-FAME CAREER

The NFL continued, but team size reduced from 33 players to 25, and few were spared from service. Even George "Papa Bear" Halas was called to duty. Canadeo kept playing in the scaled-back NFL for the 1942 and '43 seasons, and he was named NFL First Team All-Pro. In 1943, Canadeo was hitting his prime. This leap might be attributed to his newfound love and marriage to Ruth Toonen on Oct. 11. Ruth was an enormous inspiration, and together, over 60 years of marriage, they would raise a wonderful family of three sons (Bob, Tom, Tony Jr.) and two daughters (Mary Kay and Nancy).In 1944, Canadeo was called to serve and left Ruth and the Packers for Fort Bliss, Texas. He trained to be an antiaircraft serviceman. Ruth was pregnant, and Canadeo was allowed to return home to visit her for the birth of their son, Bob. During his leave, Canadeo was able to squeeze in three games for the Packers. The Packers finished the season as champions, defeating the New York Giants in the first and only NFL championship in his 11-year career.

In 1945, Canadeo and his division were shipped to England to help finish the war against Hitler. They moved through France and Belgium, just behind the Western Front in Germany. He witnessed the surrender of the Nazi government. Following the war cleanup and mustering out, he returned home safely in the spring of 1946 to Ruth and their son. And to football.

The 1946 Packers were a vastly different team, with only six teammates returning from the 1943 team. Don Hutson retired to become assistant coach, and Lambeau's single-wing strategy was archaic and overrun by the new T-formation. Still, the Packers stayed competitive, finishing 6-5.

When the 1947 season started, Canadeo assumed the leadership role of the Packers. While fans were eager for another championship season, the Packers fell short, finishing with another 6-5-1 season. In 1948, the Packers suffered their worst season in history, finishing 3-9. The loss of all the veterans and talent due to the war and retirements caught up, and the team fell into disarray.

However, Canadeo would not be denied another stellar All-Pro year, setting up for the 1949 season, which would be Canadeo's finest. At age 30, when modern NFL running backs are retiring, Canadeo, in excellent shape, had a flaming desire to carry the team back to its winning tradition. When the season was over, Canadeo became the first Packer and the third player in NFL history to rush for over 1,000 yards.

Despite his phenomenal season, the team's downward spiral hit bottom when Lambeau retired, leaving the Packers with a 2-10 record. But the team's woes didn't diminish Canadeo's amazing year. He was one of that era's NFL greats.

The end of 1949 and the season of 1950 were filled with turmoil and discontent. The Packers started the rebuilding process with a new coach and new players. It would take a decade for the Packers to resume their winning ways. Canadeo hung in with the changes for the 1950 (3-9), '51 (3-9) and '52 (6-6) seasons, mentoring younger players. In the 1952 season, after 11 years, he decided it was time to retire.

Canadeo played his last game in Chicago at Wrigley Field, with friends in the stands watching. The Packers pounded the Bears 41-28, and his teammates presented him the game ball.

On Nov. 23, the Packers declared "Tony Canadeo Day," holding a ceremony before a home game against Dallas. He was honored by several present and retired players and received a new Chevrolet station wagon from the Green Bay community. The Packer Band played the Gonzaga fight song and presented him a "salute letter" from Bing Crosby. In addition, the Packers bestowed the highest honor on him as they had with Don Hutson, by retiring his No. 3 jersey, never to be worn again by another Packer player. In fact, while the Packers have 33 NFL Hall of Famers, Canadeo is one of only six in the team's century-plus history to have his jersey retired.

The Packers defeated the Texans that day, and the season ended at 6-6. "The Gray Ghost of Gonzaga" hung up his cleats, holding many Packer records including being the leading all-time rusher. (Even all these decades later, he still ranks fourth in rushing yards.)

BACK IN THE HUDDLE AGAIN

Like most NFL players of that era, Canadeo's favorite day was "game day," but his least favorite day was "payday." He played for the love of the game and didn't make much money; all NFL players had jobs to support their families. Thus, upon retirement from football, Canadeo dove into his new role as a salesman for Production Steel. As expected, he was a top salesman, dedicated and focused.Then, in 1955, football came calling again when Canadeo was named to the Packers Board of Directors. He was an adviser on construction of the new city stadium completed in 1957. So impressed was Packers President Dominic Olejniczak that he named Canadeo vice president and member of the executive board of the Packers.

This executive position made Canadeo one of the generals of the Packers organization — a group that would turn the 1960s-era Packers into one of the greatest dynasties in American sports history. Canadeo played a major role in recruiting Vince Lombardi to be Green Bay's new coach. Both feisty Italians, the two became very close friends, golf partners and confidants. Their spouses and families became close as well. With Lombardi running the Packers from 1959 to 1967, the Packers won five NFL championships; the Super Bowl trophy is named for him, as he continues to be considered one of the greatest coaches ever.

In 1974, Canadeo was awarded the highest honor given to any professional football player. He was enshrined in the NFL Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. Out of all the NFL players, there are only 378 with this honor. The only two Gonzaga players to be inducted into the NFL and NBA halls of fame are Canadeo and John Stockton. Ray Flaherty, who played at Gonzaga in the 1920s and won three championships as a coach and player for the New York Giants, was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame as a head coach.

Canadeo's legacy shines most brightly inside the Green Bay Packers organization. After all, unlike at Gonzaga, they still play football. Canadeo is remembered in Green Bay with the highest respect and regard in the Packer organization and among fans whose sense of history runs very deep. Canadeo also holds the longest record of service with the Packers, spanning 60 years. That organization's enduring excellence has people like Canadeo, Lambeau and Lombardi written all over it.

But Canadeo's story also reflects his time at Gonzaga, as he lived his life by the principles that Gonzaga's faculty, coaches and Jesuits taught him. His story is a glimpse of a forgotten time, when they played college football on Gonzaga's campus and scholarship athletes still had to work for their tuition. For too long now, Canadeo has been the forgotten Zag.

Somehow, someway, when a fan looks up into the rafters of the McCarthey Athletic Center, it seems fitting that there be a spot to recognize the great Tony Canadeo and the late, great Gonzaga football program. Let's make this happen: The jersey numbers of Gonzaga football legends like Houston Stockton and Ray Flaherty should join Tony Canadeo's No. 13 and hang from the rafters for all Gonzaga fans to see. They earned it. ♦