It's October 22, 2001, and I'm standing on a crowded Key Arena concourse. And I should be excited, but I'm not. That's because I'm watching the fifth game of the American League Championship Series on a tiny screen above a concession stand.

My friends are at their seats, waiting for Pearl Jam to hit the stage for a charity gig, playing a split bill with REM. I've flown up from my freshman year in college in LA to see this show, and I'm getting dangerously close to missing the opening chords. But I need to see this.

Minutes later, Mike Cameron sends a weak liner out to right, it's caught, and the game is over. The season is over. The dream is over. The surety of a Mariners World Series all but guaranteed by 116 wins and the mystic wonder of Ichiro's arrival has disappeared.

That's the last moment of Mariners playoff baseball on record. There has not been one inning, one pitch, one fluke Wild Card appearance since. This fall, the Mariners playoff drought is in danger of reaching legal drinking age, adding to its streak as the longest gap between postseason appearances in major North American sports. Additionally, the Mariners, despite existing for 46 seasons, have not only never won a World Series, they're the only team in baseball to have never even been in the World Series1.

If you ask the people who've been tuning in for the past four-plus decades, they'll say there's a chance it changes this year. The problem is that some of those people have told you there's a chance every April. And sometimes you believe them, occasionally for good reason. And, shit, sometimes the actual team makes you believe — maybe by snagging a world-class second baseman from the Yankees or allowing one of the greatest pitchers of his generation to hold court.

Sometimes, they let you believe all the way to September, and then October leaves you ashamed by the gullibility that you tell yourself is loyalty. But you know it's not. It's just Seattle Mariners fandom, and it's weird, and sad, and strangely alluring. It's not like you watch the World Series each year hot with jealousy. That's because we Mariner fans don't see our team as existing in the same universe as the teams that win the World Series.

We're like an orphan in some Victorian novel who isn't jealous of the rich kids because our brains can't imagine any life other than the one we've been dealt.

1 The other teams that have never won a World Series (but have each appeared in at least one Fall Classic) include the Rays, Rockies, Rangers, Brewers and Padres. Since the last three on that list have existed for longer than the Mariners, their World Series win drought is actually longer than that of the Mariners. This provides little comfort.

It's a spring evening in 1988, and the Kingdome is probably very empty2 and the Mariners are probably playing very poorly.

My folks have packed my brother, sister and me into the back of a 1982 Chevrolet Monte Carlo, the seats so low that we can't see out the windows, leaving us woefully susceptible to car sicknesses should trips run more than an hour. Thankfully, we're heading down I-5 from what's yet to become a sprawling metro area north of the city, and can travel the 23 miles to the Kingdome in puke-defying times.

We exit a few stops short of the stadium and find free parking. We walk the better part of a mile on some not-so-savory streets, lugging in tow a backpack of microwaved popcorn and other snacks.

OPENING DAY IN SPOKANE

When Spokane baseball fans aren't watching the Mariners on TV, they can obviously watch tomorrow's diamond stars today courtesy of the Spokane Indians. Currently a minor-league affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, the Indians open their 2022 season at Avista Stadium Friday night, April 8, against the Vancouver Canadians. The first pitch is at 6:35 pm; tickets range from $8-$22 and available via spokaneindians.com.My dad carries at least one of us into the game and pays about three bucks a ticket for the adults and whichever kids have become too heavy. Using the coupon on the back of our ticket stubs, we pick up free ice cream sundaes at Dairy Queen on the way home. The outing, I'm told, costs less than $20 total.

Inside the Kingdome, on those cold maroon outfield bleachers, we watch guys like Harold Reynolds, Jeffrey Leonard and Mr. Mariner himself, Alvin Davis. We have Dave Valle behind the plate and a rotating cast of mustachioed bums on the mound. Edgar Martinez is honing his hall-of-fame swing while roaming the turf around third base, and midway through that season a rifle-armed right fielder named Jay Buhner arrives in town.

The Kingdome, like the Mariners, seems nothing but normal to me. I see nothing wrong with watching baseball beneath the cover of 250 feet of gray arching concrete, even if it's a perfect 72-degree July evening in Seattle, of which there are many. I enjoy galloping up the steps, my shoes sticking to the spilled beer in the aisles, so I can race to the men's room and piss alongside a dozen grown men at a 12-yard-long trough. I applaud Rick the Peanut Man3 as he whips foil-wrapped nuts across 10 aisles from behind his back with the gravitas of a true showman.

In later years, there's a "kids run the bases" promotion after a game, and we stick around, waiting in a too-long line to walk the paths of our heroes. We finally get out there, and my brother and his friend take off on a dead-ass sprint. They round third and promptly plow into a bunch of kids just short of home plate in a cloud of dust. We are asked to leave immediately.

But we are down on the field. We feel the hard and unforgiving turf, and up close I can see the tobacco-spit stains. It's very close to heaven.

2 The Mariners did not sell out a game at the Kingdome until 1990 — their 14th year in the league. Like many unflattering pieces of Mariner history, this anecdote seems both utterly believable and impossible at the same time.

3 Rick Kaminski was a Vietnam veteran who worked at Mariners games upon their inception. An ESPN segment once clocked his behind-the-back toss at 72 mph. He died in 2011 of brain cancer and was honored with a moment of silence before the game.

It's May 5, 1991, and the Mariners are playing the Yankees4 on ESPN Sunday Night Baseball. This is a big deal for us in the wilds of the Northwest who both dismiss national sports media while also yearning for the spotlight.

The game5 starts just after 5 pm, and my family and I are tuned in on the basement TV. But it just keeps going, and I'm sent to bed around the 11th inning. I have a clock radio, though, and I get under the covers and tune into 710 AM and listen to Dave Niehaus call inning and after inning of scoreless baseball.

The Yankees score in the top of the 16th inning — it's already the longest game in Kingdome history — but then Omar Vizquel hits a double down the right field line, bringing Greg Briley to the plate. Briley stands 5-9, wears glasses, has gone 1-7 thus far in this marathon game, and has hit only 19 home runs in his career as he digs into the box.

Improbably, he launches a ball over the tall scoreboard in right field, and Dave Niehaus' voice goes into that high, blessed octave that delivers only good news to tell us the Mariners have won the duel. I jump on my bed and scream, giving up the illusion I'd gone to sleep hours before. I do not get grounded. Rather, I develop a habit of going to bed on time and clandestinely dozing off to Niehaus' smooth, pack-a-day grandfatherly growl via my trusty clock radio.

When the Mariners arrived in 1977, Niehaus6 was tasked with calling games on radio and television — day in, day out, for all 162 games, as well as spring training and hopefully something extra in the fall. One could argue that Niehaus was dished the same job description as the 29 other announcers in the league. But Niehaus did more because he had to. He was building a culture. He was shamelessly positive and hardscrabble all at once — so perfectly Northwest.

When he died, I had a self-understanding that I'd met Niehaus at least once, despite the fact that I had no evidence of such a meeting. The man's voice had been omnipresent for springs and summers and a few falls since my birth, so it makes sense. He talked to us on car rides across the state and camping trips and quick drives to the grocery store. He was in the garage as my dad worked on his car. On this night, though, he's just the happy guy on the other end of the radio telling me that the Mariners have won.

4 The 1991 Yankees came into this game 7-14. They'd finish the season a staggering 20 games under .500.

5 ESPN was excited to broadcast this game given that the previous night, Yankees leftie Chuck Cary threw a fastball directly at Ken Griffey Jr.'s face. With the next pitch, Junior responded by intentionally losing the grip on his bat and sending it at Cary. Tempers flared, benches emptied, etc. The possibility of a brawl on national TV was quite real that night.

6 If you are a casual fan, you may better know Niehaus from the Macklemore song and its accompanying video "My Oh My."

It's June of 1993, and my dad has scored seats in the second row on the first base side from an insurance guy or banker or someone else with access to such tickets. They're the best seats we've ever had. It's about the seventh inning, and Ken Griffey Jr. is at bat. The Kid has been raking this year, and every at-bat was a chance to see something remarkable. But he draws a rather unremarkable walk.

Griffey is standing on first base waiting on a pitching change, staring blankly out into the crowd. My friend and I start waving wildly with both arms, yelling something dumb like "Hey Junior!" Then it happens. He locks eyes with me and waves. It's a little wave, mostly with his fingers tapping his palm, but it might as well be a bear hug.

At this moment, my feeble existence has been recognized by a man, who at only 23 years old, is already the most talented athlete in professional Seattle sports. He's also far and away the most famous person in the Northwest, and in a few short years will become the most famous baseball player in the world by a wide, wide margin.

Griffey was an instant celebrity when he arrived in Seattle at just age 19. In his third year on the team, a Seattle-area trading card company created a Ken Griffey Jr. chocolate bar7. I remember making my mom drive us around until we found one. Once unwrapped, the bar featured a semi-likeness of the Kid (if you squinted and held it at arm's length) that you could sink your teeth into, or more likely, save to show the buddies who couldn't find the bars anywhere.

If you look at all my baseball pictures from coach-pitch through high school, you likely won't find anyone wearing a No. 24 jersey. To allow that number amid the pile of jerseys allotted to a youth team would be to invite violence into the dugout. Kids would die to share Junior's number on their back. I have a feeling that as the years went by, this phenomenon extended far beyond the Northwest.

It was a strange sensation that by 1996 Griffey's fame outshone that of the Mariners and even Major League Baseball itself. We had to share this guy with the world. He was everyone's star now. In fact, so bright was Griffey's star that in 1996 Nike launched a campaign in which Griffey, although constitutionally prohibited by his young age, was running for president of the United States8.

The ads were everywhere, and so was Griffey. In some ways, he was a backward-wearing, hip-hop-listening, horseplaying iconoclast who shrugged at much of baseball's unwritten rules. At the same time, he was the star that baseball needed after a strike-shortened season canceled the 1994 World Series and left many fans disgusted.

But by February 2000, Griffey had made it clear he was done in Seattle, and he was traded to his hometown Cincinnati Reds. The Mariners got in return many of the tools that helped set up their subsequent playoff runs, but that didn't make the trade any less devastating. I came home from school and removed the two Griffey posters from my walls. I bought a shirt that read "Ken Who?" across the front and wore it to games at Safeco Field that summer.

I was scorned and devastated, but I'd always have that wave.

7 Griffey is allergic to chocolate, but nevertheless tried the bar. He reportedly soon broke out in a rash, but said it was worth it.

8 "People don't want someone coming out of left field. And they sure don't want someone who plays too far right. Griffey's in the center, perfectly positioned," said storied political strategist James Carville in one of the TV spots. A "Griffey in '96" button sits in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It's Oct. 7, 1995, and I'm hearing the loudest sound my 12-year-old ears have processed. It's a roar, then something beyond a roar, like all the sound has collapsed in on itself and my brain is registering sonic chaos.

Seconds earlier, Yankees pitcher John Wetteland9 piped a fastball down the middle of the plate with the bases loaded, and Edgar Martinez, as he is wont to do with such fastballs, powers a line drive over the center field wall and into the massive tarp used to cover up seats used for the football version of the Kingdome.

When the roar lessens a few decibels, the man in charge of the PA system loads up "Shout," and the place parties down for the entirety of the ensuing pitching change. My brother and I are shaking each other in disbelief. My mom and dad are dancing like moms and dads. My sister is spending the night at a friend's house because we could only get four tickets, and I still feel bad she missed this.

The people listening on the radio hear Dave Niehaus add another memorable like to his gospel: "Get out the rye bread and the mustard this time, grandma, it's a grand salami. The Mariners lead it 10 to 6. I don't believe it! My, oh my!"

It's almost cliché to talk about the magic that baseball brought the Northwest in the fall of 1995. But after a quarter century of retrospect, what happened that autumn does not feel any less remarkable.

On Sept. 19, 199510, voters in King County rejected a tax package that would have subsidized a new stadium for the club. Given that Mariners ownership had insinuated that they would likely sell the team if the tax wasn't passed, it's not inaccurate to say that residents used the ballot box to signal their ambivalence toward their baseball team.

Like most seventh graders at the time, I'm gleefully ignorant of tax policy and its resulting effects, as I scour the standings in the newspaper each morning before school. The Mariners have never mattered after Labor Day my entire life, but now they've become a soundtrack to our suburban life. We're late to Mass because we need to stay in the car and hear the M's record the final out. We sneak a radio to a Boy Scout campout to hear Griffey blast a go-ahead homer. It's a moveable feast of possibility.

And that feast overtakes my middle school on Oct. 2, as the Mariners face off with the California Angels in a one-game playoff for the American League West pennant. The game begins early in the day, and we go from class to class with updates that the game is still a 0-0 tie. Then the wiser public educators in the building give up and forgo lessons for the day, as signaled by the hollering heard through the walls when Luis Sojo hits a ball off the ill-positioned bullpen bench with the bases loaded and ends up with a (sort of) inside-the-park grand slam. Randy Johnson closes out yet another complete game, and we watch with pre-pubescent jubilance as fans storm onto the neon turf and celebrate. To my knowledge this is the last time fans stormed a major-league field.

The goddamn Seattle Mariners are in the playoffs. And now I'm right there in the middle of it. In the actual sold-out Kingdome for a must-win Game 4 of the ALDS that now looks like a sure-win after Edgar's salami. After the final out, we head out into the night chanting with thousands of others drunk on a cocktail of Refuse to Lose11-ism, Rainier beer and defiant optimism for Sunday's Game 5. Some quarter decade later, it's still the most exciting moment of live sports I've witnessed.

The next day, my friend's dad shuts down our garage band practice12 and takes me home just in time for everything that was to come. Edgar doubles to left field. Griffey motors around the bases and slides home. There's a dogpile at the plate that somehow includes a young Alex Rodriguez and fireworks drop from atop the concrete dome.

A month later, shortly after the Mariners lose in the American League Championship Series13, the state Legislature paves a path forward for a new stadium.

There will be Major League Baseball in the Northwest for years to come.

9 Wetteland's history after this pitching outing is worth noting. He'd go on to be named the MVP of the 1996 World Series and lead the league in saves. His coaching career included a stop as a bullpen coach for the Mariners during which he was hospitalized for a mental health issue. Shockingly, as of print time, he is standing trial in Texas for child sexual abuse.

10 On the day of this vote, the Mariners trailed the Angels by one game in the AL West.

11 "Refuse to Lose" became the official slogan of the 1995 Mariners run. The slogan felt like a self-curse after the Mariners went to New York to kick off the series and dropped the first two games of the series.

12 At this time, we only knew one song, a Nirvana B-side called "Sappy." We were terrible, even for 12-year-olds.

13 For as much as I recall about the Yankees series, the opposite is true of the ALCS against Cleveland. All I remember is that upon losing the series at home, the fans stayed and cheered until the players came back out on the field, tossing autographed balls into the stands. This was heartwarming, but in retrospect may have been a harbinger of the mediocrity to come.

It's May 16, 2009. I'm living in Oregon, and my wife and I have come north to see the Mariners play the Boston Red Sox at Safeco Field.

Ken Griffey Jr. has improbably returned to Seattle to finish his career. This is the guy whose poster I'd torn down when he went to Cincinnati and whose name I'd cursed and promised to forget. It turns out that I still very much love Ken Griffey Jr.

He is slower and bigger and serving only as a DH, but good lord, that sweet-ass swing is still there. It's not lost on me that his return to Seattle did little to move the needle toward winning, but I've read enough scripture to recognize a prodigal son when I see one. Despite the crowd consisting of more than a one-third Red Sox fans, it's electric to hear "Hip Hop Hooray" when Griffey comes to the plate.

Griffey has brought me back to the Mariners. I'd never stopped following the Mariners, per se, but I was in LA for the good post-2001 Ichiro-led teams that got a raw deal by residing in a great division, following along through box scores and a couple rare ventures to Anaheim to see the M's in enemy territory against the Angels. I felt like an acolyte who'd lost his way, but had again seen the light. The problem, however, was that the light was often terribly dim.

Junior (even this lesser iteration of the man) sends me deeper in than I've been in a long while. I'm tuning into Root Sports nightly. I'm asking bartenders to put the game on if it's close. I'm putting my eggs in a basket that I'm pretty sure will break them.

It's Aug. 15, 2012, and I'm sitting in a bar in Pullman sharing my attention between a Wednesday matinee Mariners game and my flip phone. I've been in town to profile new Washington State University football head coach Mike Leach14 for this publication, and my one-on-one interview has been canceled, but I'm still hoping for a call before I leave town.

Sure, I'm killing time, but I also need to be in this bar right now eating this burger because it's a Felix Day, and I want to see at least a bit of this game on TV. In this season, and several before and shortly after, my Mariners fandom has become myopically focused on every fifth day on the calendar.

Felix Hernandez has become a singular competitive entity for many of us, and this is kind of terrible because the Mariners' offense has become painfully and consistently anemic whenever the King takes the hill. There are enough believers in this man that the Mariners have devoted an entire section of the stadium for matching T-shirt-wearing devotees to cheer on one of the greatest pitchers of his generation.

This burger is dusted, and my phone hasn't made a chirp, but Felix cruises past the Tampa Bay Rays, thanks to a few nice outfield plays and key strikeouts. I watch another inning. No phone call. But Felix is dealing. I get in my Ford Ranger, adjust the dial to find the game, and head back to Spokane. It occurs to me that it's the end of the fifth inning and Rick Rizz has noted that Felix has sat down 15 consecutive batters.

Somewhere outside of Colfax, Felix strikes out the side, and there's some extra sauce in Rizz's voice as we drive deeper into the game. But because it's the 2012 Mariners, they have scored only one run, and the main focus is less on history and more on eking out the 11th win for Felix in an otherwise forgettable season.

Felix, though, was never forgettable, even in those dark seasons. The guy first took the mound at 19 years old, something that will probably never happen again in the major leagues, and decided to make Seattle his home. Whereas Griffey became an international superstar, Hernandez became one of the tragically underrecognized pitchers in modern baseball15. Still, he was beloved in his city and oddly loyal to a club that never surrounded him with the team he deserved.

When Felix left the field for the last time at the end of the 2019 season, he cried mightily, as did his teammates. As did I. For me, it was a mix of gratefulness with a whole lot of what-if mixed in16. The guy deserved better.

But on this day, seven years earlier, I'm flying up Highway 195, a route I've been repeatedly told you should not fly up, in need of cable television. It's the top of the eighth as I get stuck behind a truck chugging its way up the back of the South Hill as Felix quickly strikes out the side. I uncharacteristically and unapologetically pass the dude on a two-lane road next to a country club and skid to a stop at my house just as we enter the top of the ninth.

You know the rest. Felix does the damn thing. He strikes out Sean Rodriguez, then throws his hands to the sky, kisses both wrists and gets mobbed by his team.

The following Christmas, my wife gifts me a framed picture of Felix celebrating this moment. When my son is born a few months later, I mount it above his crib.

14 In reporting this story, I realized that this man is an asshole, a fact I intentionally omitted from that profile out of benefit of the doubt, and for which I apologize.

15 It must be noted that Felix won the 2010 Cy Young in the most Felix-y way possible — by posting a 2.24 ERA, yet only posting 13 wins.

16 Sadly, a very similar event transpired when manager Scott Servais pulled career-long Mariner Kyle Seager from the last game of the 2021 season. Kyle also deserved better.

It's Oct. 2, 2021, and I'm in Dana Point, California, to see Pearl Jam.

Neither the Key Arena nor REM have survived the Mariners playoff drought. But apparently Pearl Jam and I came out on the other side. The hundreds of other folks in Mariners garb at this two-day, Eddie-Vedder-hosted festival seem to have kept the faith, too, and we gravitate toward each other for brief "how 'bout them M's?" optimisms. The Mariners have won far more games than anyone expected, and they're playing meaningful baseball in the first week of October.

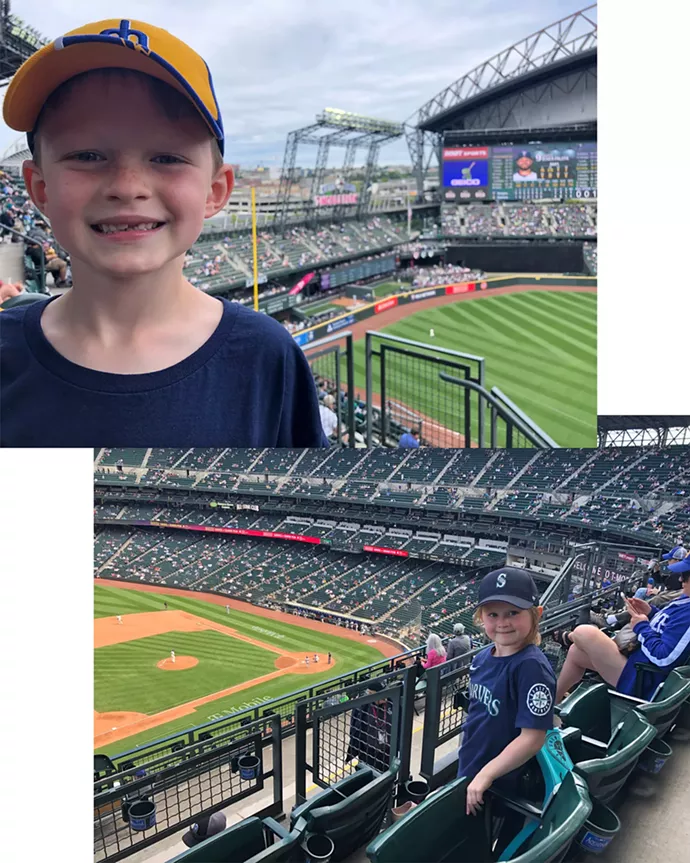

I didn't see this coming when my wife and I took our two kids to their first Mariners game over Memorial Day weekend. In those limited-attendance days, we were just grateful to be in the park, and to take advantage of the Vaccination Celebration promo discounts throughout the stadium that delivered cheap beers17 and affordable kids gear.

The Mariners won that game. And they won a lot of other games along the way, and brought up dudes from the minor leagues like Jared Kelenic and Logan Gilbert, giving us uneven results but a look at our future. Then by September, guys like JP Crawford, Ty France and, of course, Kyle Seager, started Refusing to Lose. Folks started flooding into T-Mobile Park for that last weekend home series, and yellow "Believe" posters18 dotted the outfield railings.

I wasn't at T-Mobile Park19 on that October evening, of course. Rather, I was hunched next to the grandstands for better service to see in-game updates20 on my phone as Mitch Hanniger came through for the third time that game to put the Mariners ahead and top the Angels. Shortly thereafter, Eddie and company launched into "Alive," a cut almost too on the nose for Mariners Nation.

The next day, however, the Mariners are eliminated from the playoffs on the last day of the season.

17 For $9, you could get a draft-poured pint of Bodizafa IPA from Georgetown. Unheard of in modern stadium pricing.

18 These posters were clearly modeled after the hit Apple TV show Ted Lasso in which the titular character's team loses after displaying this sign. Apparently the M's entire marketing department stalled out on episode 6 and just signed off.

19 I will never get used to that name. I'd rather call it the Kingdome.

20 Interrupted by spousal texts like "where did u go?"

It's the last week of March 2022, and I've done the thing a Mariners fan shouldn't do in 2022 — I'm on Twitter.

Mariners Twitter is a depraved corner of sports fandom in which advanced metrics (my least favorite aspect of modern baseball) cloud basic common sense, and there's little consensus on how the M's will look this year. There is some agreement, however, about the Mariners front office in that they seem to "try" to build or rebuild a squad, but fall short in free agency.

I typically don't pay too much attention to spring training. This likely makes me a lesser fan, but I think of it as self-care because there are 162 games ahead of us, and my tender mental health can't take more than that. Call it self-preservation, if you will, but the possibility of not having a season as this winter's labor negotiations dragged on was enough anxiety for me.

But goddamn. This could be the year. The Mariners have some young studs. They went out and got a Cy Young winner. They have guys who've played in actual All-Star games. They have guys with that old-school Mariners grit, like Mitch Hanniger and Marco Gonzalez.

This could be the year. Or maybe it's next year. Or maybe another 20 years... ♦

Mike Bookey is a Spokane resident, Mariners lifer, and was Inlander Arts and Culture editor from 2012-2016. He is a firm believer in the designated hitter.