“There is an element of mystery behind it. I think that people are really intrigued by the circus,” says Kaiser. “It’s not just the event but the people who dedicate their lives to this sort of performance.”

This week, the Jundt opens a new show, entitled “Damn Everything But the Circus,” a collection of 30-plus prints picked from the museum’s 4,000-plus-piece permanent collection that depict —” in vastly different styles and media —” the intrigue, romance and, at times, the dark side of the circus.

The name of the show is also the title of an E.E. Cummings poem, which also helped inspire the selection for the display. It reads:

Damn everything but the circus!

. . . damn everything that is grim, dull,

motionless, unrisking, inward turning,

damn everything that won’t get into the

circle, that won’t enjoy, that won’t throw

its heart into the tension, surprise, fear

and delight of the circus, the round

world, the full existence . . .

The poem captures the romanticism that inspired so many artists during the early years of the 1900s and continues to spur creative works, although to a lesser extent, today. One of the most well-known artists to dive into the world of the circus was Pablo Picasso, whose “Rose Period” between 1904 and 1906 included a number of depictions of clowns and other circus performers. For a while, the artist seemed all but obsessed with the circus.

Some have called this his “harlequin” period, and have interpreted it to symbolize the outcast nature of the artist. The harlequin was the epitome of the artist and Picasso, some art historians say, was pointing out that there was no difference between the fine artist and the circus clown.

While Picasso was using the circus performer as a metaphor, other artists were similarly drawn to the romanticism of the circus ideal and its role in American —” and European —” culture. According to Kristin Spangenberg, who curated the Cincinnati Art Museum’s circus poster and history exhibit, one of the most comprehensive displays of its kind, there were more than 100 traveling circuses steaming across the country at the turn of the 20th century.

“It was a unique form of entertainment. The only thing they were really competing with was the theater and the beginning of cinema,” says Spangenberg.

The circus —” which has existed in Western culture in one form or another since antiquity —” was also one of the most artistically depicted events during its heyday. In fact, Spangenberg says that the circus was at the forefront of wide-scale outdoor advertising. Circus companies would typically create intricate poster prints —” which themselves were sometimes dynamic pieces of art —” that would be plastered throughout a town in which the circus was set to soon appear. It was this omnipresent imagery, Spangenberg says, that played a part in inspiring artists of the era to dive into the world of the circus.

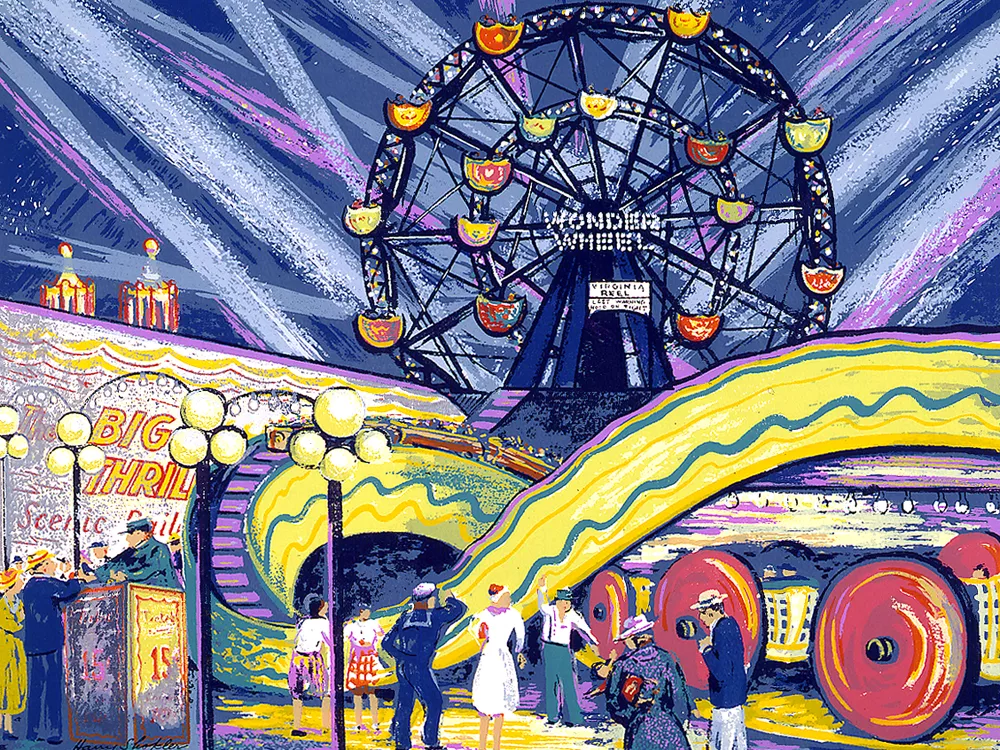

The show at the Jundt features paintings, lithographs, woodcuts and photographs, most of which were created during the 1930s and ’40s, but range in date all the way to 1982. Many, like Harry Shokler’s 1942 creation “Coney Island,” employ the bright colors and dynamic shapes that elicit the jovial nature many associate with the circus. “Carnival” by Hananiah Harari is one of the most obscure and abstract pieces that capture the whimsy that comes along with the big top.

Other pieces, however, are stranger, darker and emblematic of the mysterious and sometimes outsider nature of the circus.

“Some of the prints are very colorful and bright and others are, well, a little creepy,” says Kaiser. “We think of the circus of having sideshows and other curiosities and that’s interesting to people, also.”

One of these pieces is by Reginald Marsh. It’s a black-and-white print of his drawing depicting the depravity, gluttony, chaos and bizarreness of the circus and the events surrounding it. If you’re scared of “carnies,” this piece should validate those fears.

The show is also, and perhaps most importantly, a history lesson. But on the other hand, it also serves to explain why we’re still fascinated by the circus, even if we’ve never actually seen a circus.

“It’s a part of our culture, definitely, and it’s almost entirely visual so we know what to expect: the big top, the red and white stripes, the ringmaster’s costume,” says Kaiser. “There’s still a lot of romanticism to it.”

Damn Everything But the Circus —¢ Aug. 17-Nov. 17 —¢ Jundt Art Museum at Gonzaga University —¢ 202 E. Cataldo Ave. —¢ 313-6611