By the time President Barack Obama finally announced Osama bin Laden’s death on television on May 1, 5,000 tweets were firing off every second — a torrent of speculation, celebration, off-color jokes and rumors.

Twitter users knew (or thought they knew) what was coming before TV viewers did.

“So I’m told by a reputable person they have killed Osama bin Laden. Hot damn.” That was Keith Urbahn, chief of staff for former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, posting to Twitter from his Blackberry. Urbahn had heard the news from a TV news producer, wrote the post, got “retweeted” by a New York Times reporter, and soon the news was spreading like a virus.

In the meantime, media outlets were scrambling, calling sources and, without on-the-record confirmation, reporters were reticent to say what they knew. Twitter had no such reluctance: Immediacy is king.

For input junkies, for those who love the flood of commentary, wit and information — accurate or inaccurate — the online frenzy surrounding bin Laden’s death was exhilarating. But for journalists, the sort who believe reporting necessitates multiple, reliable sources and context, it’s a brand-new challenge: Not only do they have to compete with the speed of unsourced news leaking onto Twitter; they also have to play cleanup, squashing lies and fast-spreading conspiracy theories.

When a newspaper gets something wrong, the punishment is a diminishing respect for the offending news organization. Not the case for a Twitter user spreading a bad rumor.

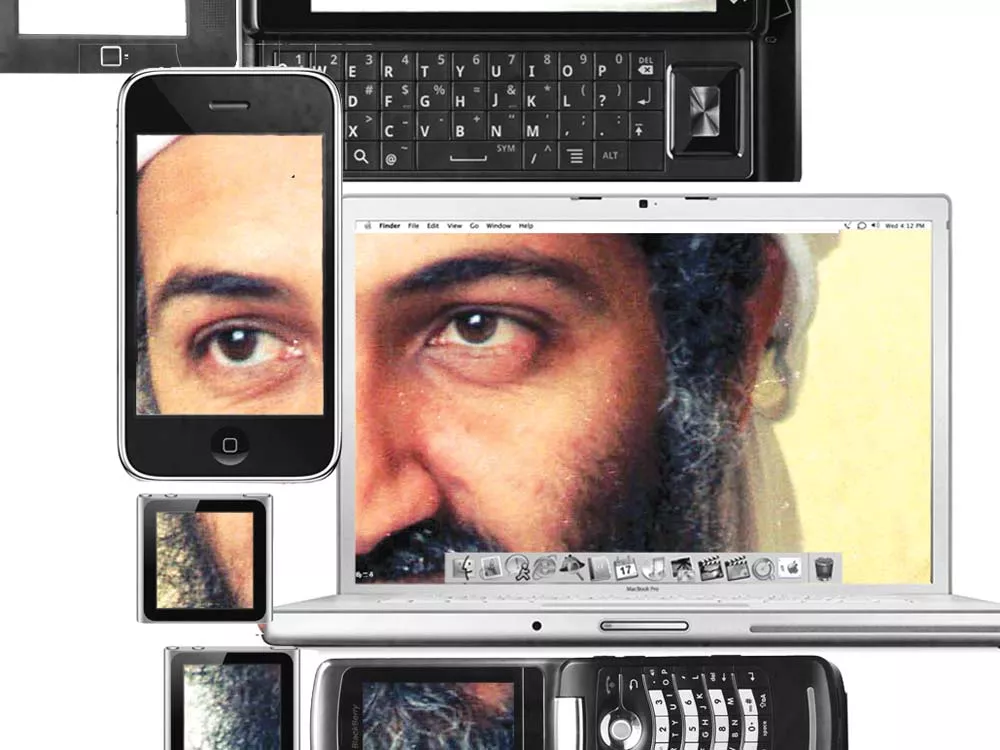

When gory pictures of bin Laden surfaced on the Internet within hours of the big announcement, they spread rapidly across Twitter. Some news outlets picked them up, and at least three politicians thought the images were real. It fell to journalists like those at the Guardian to explain that it was an obvious Photoshop job from 2009.

The death pictures went viral in another way as well: Hackers used the promise of links to death pictures to spread viruses to take over users’ computers.

The social media site also propagated conspiracy theories and other nuttiness. Anti-war protester Cindy Sheehan posted, “I am sorry, but if you believe the newest death of OBL, you’re stupid.”

One of the most widely circulated reactions to the bin Laden news came not from paid pundits but from a 24-year-old Penn State graduate named Jessica Dovey. Like many her age, Dovey wrote her thoughts about bin Laden’s death on Facebook.

“I will mourn the loss of thousands of precious lives, but I will not rejoice in the death of one, not even an enemy,” she posted, following it up with a Martin Luther King, Jr. quote, containing similar sentiments, from his book Strength to Love.

Somehow her Facebook update caught the attention of Penn Jillette, the magician and TV host. Jillette forwarded it on Twitter, and it exploded: Her quotations marks were lost, and suddenly, thousands of tweets and Facebook status updates were crediting her words to MLK. It took writers from the Atlantic, the Washington Post and the Detroit Free Press to persuade readers that, no, Martin Luther King, Jr,, did not say that entire quote.

The episode underscores the strength and weakness of our new media age: Anyone, with a stroke of luck, can have their insights, discovery or first-hand accounts spread across the world in a few days. Log on to Twitter and you become part of a lively, worldwide discussion where ideas and information are shared instantly. No need to wait for Anderson Cooper.

But also without that traditional filter, news and facts are scrambled together with lies and rumor. It’s exciting to watch, but discovering truth gets complicated.