I always think of writing an article as putting a puzzle together, except I have too many pieces. It’s my job to gather more information than I need — that way, I can choose the best bits and piece them together in a cohesive way. It’s exciting, and serious, and sometimes, extremely frustrating.

I realize now that it’s mostly absurd to write about an entire life in 4,000 words, the typical length of an Inlander cover story. But when I first pitched a story about Eleanor Barrow Chase, I didn’t know how much information I’d find. When my editor liked the idea, I asked if he'd be willing to drop the word count to 3,000, or even 2,500, if need be. Oh, sweet naivete. By the time deadline came around, I had so much information that I was trying to cajole him into letting me write 10,000 words.

He said no. So I actually did my job and chose what I hope were some of the best 4,000 words for the limited space we have each week.

Still, left over in my phone, a Google Drive folder, a notebook and some random scraps of paper are plenty of facts that are interesting and important but didn’t make the final cut. As I’m clearing my desk to make room for the next puzzle, here are a dozen extra tidbits for anyone interested in learning more about the life of Eleanor Barrow Chase. You can judge if I chose the right words or not.

Eleanor had programs from Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes because they each performed in Spokane. Eleanor’s signed program from Marian Anderson was from Anderson’s performance at the Fox Theater, but Anderson’s better known performance in Spokane was at the Davenport, when there was some kind of scandal. Anderson performed at the Davenport in 1937, according to Jerrelene Williamson’s book African Americans in Spokane. Eleanor said Anderson was one of the first Black singers to perform at the Davenport, and that Anderson wasn’t able to go in the front of the building but was forced to go up the back elevator instead. “I think people were so enraged about her having to go through the back that that didn’t happen again,” Eleanor said in her interview with Eastern Washington historian Al Gill. But the account in Williamson’s book is different. She includes a story of a group of Marycliff High School students, including Frances (Nichols) Scott, who were on their way to interview Anderson at the Davenport. Scott was told to take the freight elevator because she was Black. The other students all took the freight elevator with her in solidarity. Williamson says Scott went on to become the first Black female attorney in Spokane.

Eleanor’s grandfather, Peter Barrow, helped found Calvary Baptist Church. But it’s her grandmother’s name, Julia, that was carved into one of the cornerstones of the church when it was built in the 1920’s. (Before it had a permanent building on Third Avenue, the congregation borrowed meeting space from other churches in the area.)

When Eleanor’s father Charles worked for the Spokesman-Review, the people who operated the printers were called “printer’s devils” because they got so dirty when they cleaned the presses.

Eleanor had an aunt, Elizabeth Barrow, who lived with them for a few years growing up. Elizabeth taught Sunday school, and Eleanor remembered her as “quite an erudite little lady” who never married. Elizabeth moved to Seattle in 1950 to live with two of her brothers, James and Ben. On Aug. 20, 1955, Elizabeth went missing. Four months later, on Wednesday, Dec. 28, her body was found “near the Dunlap canyon Road south of Seattle…where she had apparently collapsed while walking,” according to a notice in the newspaper about her funeral service. (It seems bizarre to me that four months went by before she was found.)

In every concert that she gave, Eleanor sang both classical repertoire and traditional spirituals. For example, at a benefit for the Spokane Council of Race Relations in 1946, Eleanor sang Carissimi, Handel, Bizet, Donizetti and Wolfe, but also African American spirituals “Honor Honor,” “Didn’t It Rain,” “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child” and “My Good Lord Done Been Here.”

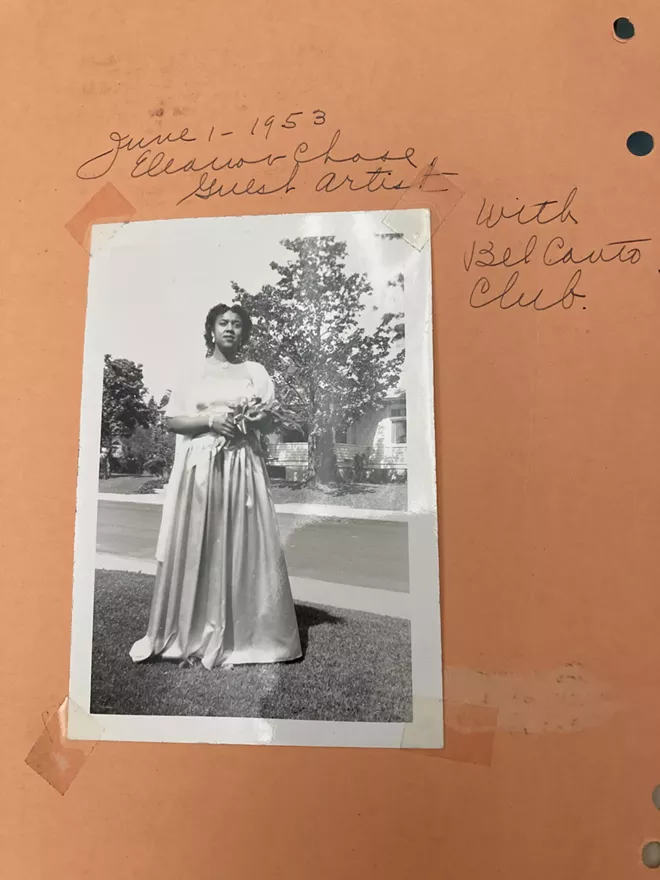

In addition to giving concerts, Eleanor was part of multiple opera productions presented by the Plastino Opera Players. She sang the lead in two of Menotti’s operas, “The Consul'' and “The Medium.” She was part of the Bel Canto Club in 1953.

Eleanor and her husband Chase were both very involved in the Masonic Order. Eleanor was a Grand Worthy Matron of Prince Hall Grand Chapter, Order of the Eastern Star, from July 11, 1978 to July 17, 1980. The jurisdiction of the chapter included Washington state; Vancouver, B.C.; Okinawa; Japan; Guam; the Philippines; Hanau, Giesen, Bremerhaven, and Kaiserslautern, Germany. There is a masonic lodge named after James E. Chase.

Eleanor and Chase couldn’t afford to go on a honeymoon after they got married. For their fifth anniversary, they took a “honeymoon” trip to Canada, but brought their son Roland and Eleanor’s mother Olive along with them.

When Chase started his first body and fender repair shop with Henry Blackwell, he couldn’t afford a car for his own family.

In 1970, Eleanor and Chase built Riviera Plaza, an apartment complex on Upriver Drive. They lived on the premises while it was being built. Eleanor was supposed to be in charge since Chase was busy running Chase and Dalbert, his auto body repair shop. But it didn’t go very well, and they sold it soon after it was complete. Eleanor later told Spokane Woman magazine, “I’m not a businesswoman. I wasn’t the type to tell anyone that their rent was due, or kick anyone out.”

Eleanor was baptized into St. Thomas Episcopal Church, her mother’s church, not Calvary Baptist or Bethel AME. St. Thomas was a congregation established in 1906 under the Episcopal Diocese of Spokane for Black members specifically, but it was dissolved in 1951 because “there is no room for a congregation which even appears to be segregated,” Fr. Ernest J. Mason wrote. “This is an experiment in Christian democracy. If you turn to with a good will, to work and worship and give along with your brethren of other races, it will succeed. If you fall by the wayside, or retreat to the racial pattern of some other denomination, it will have failed.” Eleanor’s mother, Olive, was secretary for St. Thomas Episcopal. As it closed its doors, she took time to write a brief history of the church before it dissolved and preserve important documents, like membership rolls, service bulletins and the letter from Fr. Mason. These documents are kept in the Chase collection at the MAC.

In 1988, Eleanor won the Exchange Club of Spokane’s Golden Deeds Award. She received personal letters of congratulations from Rep. Thomas Foley, Sen. Daniel Evans, Sen. Brock Adams, Gov. Booth Gardner, and Spokane mayor Vicki McNeill, who had served on City Council with Jim Chase and considered Eleanor a close friend.