EDITORS’ NOTE: As the more than 200 stories poured into our inbox for our annual Fiction Contest, my dark heart fluttered. This year’s theme — “The End” — really allowed our readers to explore and exorcise their demons. In fewer than 2,000 words, our short-story submissions covered death, violence, aging, loss and more than one zombie attack. The 10 Inlander staff judges each read through a stack of stories and selected our 25 favorites. We then read through those pieces and spitballed, argued and compromised our way to the four writers whom you’re about to read. Without further ado, we proudly present this year’s contest winners.

— Joe O’Sullivan, contest editor

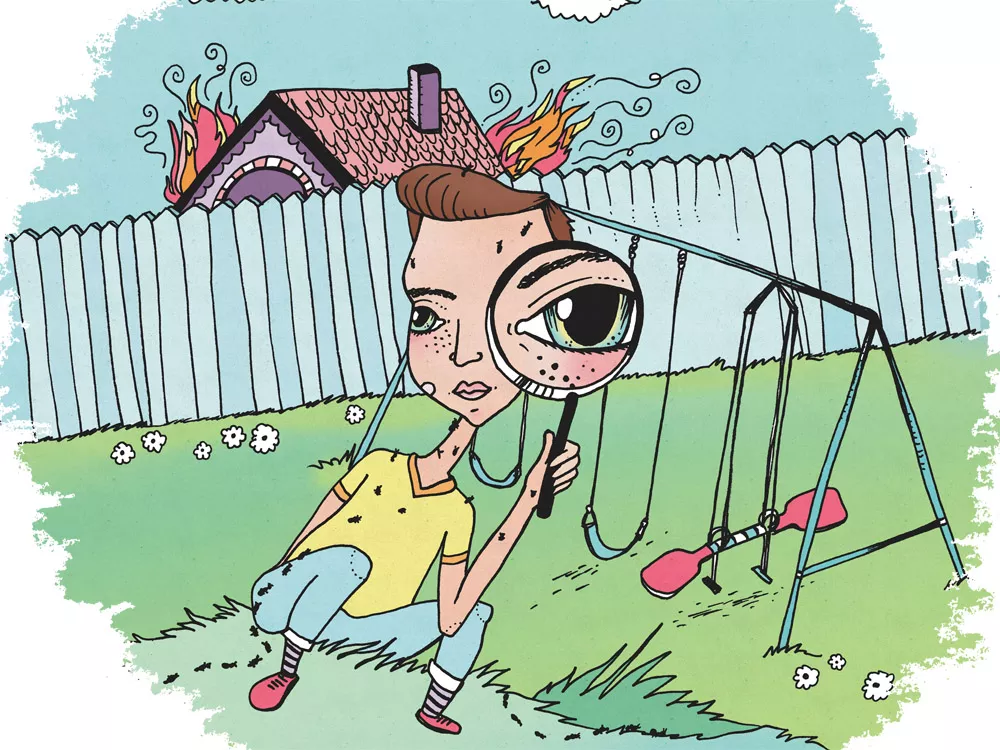

There is blood in “Red Rocket” by Skip Frazier — lots of it — but that’s to be expected. In straightforward prose, the tale of a backyard swing-set captures the strict hierarchies of justice and honor among boys running wild, and the high stakes of games invented out of boredom. Like a faded photograph of sunburned kids with scabby knees, the story unfolds into a surprisingly poignant portrait of a childhood summer. (Lisa Waananen)

Red Rocket

By Skip Frazier

Other kids in the neighborhood may have had a sweet blue Sears swing set with a four-seat glider, slide, monkey bars and three swings, or a cool multi-level tree house with electric light bulbs strung up for night time sleepovers. But we had the Value Mart swing set with two swings and a two seater rocket.

The rocket was red. The red rocket hung down on four rods and got its propulsion like any other swing apparatus — push with your feet, pull with your arms. With the legs of the swing set firmly buried in cement in the ground, the rocket could soar or glide depending on the propulsion dynamics of the flyers.

My older brother, Roger, was the real dare devil of the swing, showing us early, before we even figured out how dangerous the rocket could be, how to get the swing going as high as possible before jumping out to land on the grass in a death defying sprawl.

He set the risky standards for the neighborhood in other ways, too. He was the kid who stuck his fingers in the moving spokes of the upside down bike, showing us how to stop it. Dr. Feek sewed his middle finger back on and we were struck with a mix of awe and revulsion and confusion at his actions. He showed us how to ride a bike down a wooded trail into a huge tree at full speed. The bent fork in his bike and the knot on his head kept us from following his deed, but again we were amazed and startled by this trick. Roger could take rapid deep breaths, about 10 of them, then hold his breath until he passed out and went into convulsions. We wanted to emulate him, but didn’t so much like the twitching body part of the experiment.

Roger showed us how to start a fire with a magnifying glass. Actually, he told us about its possibility but the demonstration failed. That same day, the neighbor’s ramshackle house caught fire and burned to the ground. My mom explained to the investigating fireman how she had seen a small fire started by the sun shining through some broken glass next to Bachelor Bob’s house and the fireman found some broken glass and concluded his investigation. Thirty years later, Roger fessed up to his part of the fiasco, where he had taken his magnifying glass along with some broken glass and some matches over to the dry grass next to Bob’s house to work on his fire-making skills. Matches worked best, he said. Mom weakly denied her part of the cover up.

I took Roger’s interest in fire and did some experimenting of my own. Steve Lee and I went out to a bone dry field full of tinder crackling branches, ferns and grass and had a fire-building contest. The rules were simple: The person who built the biggest fire and could still put it out, won. If you are a quick thinker, you realize the loser is the person who builds a big fire and can’t put it out. We were not quick. I built a huge fire, kept feeding it with sticks and branches and then tried to stomp it out. I lost control of the fire, the contest and the whole field went up in a fiery holocaust. Firetrucks and bulldozers managed to save the neighborhood, but six acres of field and woods were lost. Stunningly, no one tagged Steve and I as the cause and we took the lesson seriously and never played with matches again in such a big way.

As he had with fire, Roger was able to lead us to follow his example with the rocket. He showed us how to turn the rocket into a wonderful thrill ride, full of mishaps and narrow escapes. With two people in the rocket, we could alternately pull on the rod supports and push with our feet on the bottom of the craft to gain quick lift off and achieve maximum height and acceleration. While jumping out of a swing at its apex might be exciting, Roger showed us the increased rapture of jumping out of the rocket going full speed. Like the Olympics, he’d assign style points for dismounts. Injuries counted for more than a clean landing, which somehow seemed to embolden our efforts to jump higher and fall harder onto the sun baked lawn. Scrapes, bruises, sprains were common in our efforts to glean maximum points.

After almost a complete summer season of rocket jumping, Roger creatively raised the stakes. A groove had been worn under the rocket’s flight path deep enough for children our size to lay down under the stationary rocket and see the bottom, the rivets, the sharp edges where the two halves of the gleaming red beast came together. The new game with new rules was set up.

Two people would ride the rocket, propel it into a frenzy, while the third person would lay under it, with an inch or so of clearance as the rocket blasted past. The Layer (Roger’s term for the person whose head was in peril) had to wait until the rocket whistled by five times, then had to quickly scramble out either in a forward or reverse direction, the opposite way the rocket had gone. Roger awarded different points for different escapes; crawling away would get the least, jumping up and running away, the most. All of us got clipped here and there as we worked out escapes, but no serious injuries ensued. We all had studied the rocket and knew the timing that kept us safe.

When our cousin, Jay, came to visit, we showed him various rocket games. He took to the dismount extremely well and Roger was generous giving him points since he was the newcomer and an amateur. When we showed Jay the game of laying under the rocket, he initially declined the sport. We showed him personal examples of easily made escapes and finally shamed him into taking the spot in the groove.

We forgot to calculate how the rocket, for us three brothers, had become our friend. We knew its nuances, the timing, the speed calculations, from hours of taunting its dangers.

Jay, though, saw the red gleaming missile as a monster. Laying in the dirt groove with the still rocket over him, Jay flattened himself as low as possible, trying to merge with the dirt. He whimpered a little. Mark and Roger in unison pulled on the supports and pressed with their feet in a perfect take off, screaming and yelling as was the custom while I stood back, cheering the lift off. Jay started shrieking fearfully.

I screamed at Jay to concentrate on his escape. We’d explained the art of rolling out, crawling out, quite clearly. Roll over and scramble out. Style points would come later. Still, Jay wouldn’t budge and Roger and Mark certainly weren’t going to stop and take away Jay’s chance at courage. Jay remained fearfully frozen, Roger and Mark in the rocket buzzing over his head.

Roger screamed, “We aren’t going to stop until you get yourself out!”

“Go, Jay, go now!” I yelled. “NOW!”

But he stayed as frozen as a creamsicle and kept begging for mercy.

Now the truth is that all of us had kept swing and rocket injuries secret and that secrecy had us all steeped in denial that the rocket could indeed inflict some good whacks. We knew that our dad would dismantle our treasure and haul it away if he knew of its damaging possibilities. That fact didn’t create caution in us, only made us better at hiding cuts and scrapes, or if injuries were noticed by either parent, it made us better liars.

With all three brothers exhorting Jay to quit being a chicken, a pansy, a cream puff, a weasel, a baby, we saw him finally tense to make his escape.

“Go, go, go, go, go, go, go, go,” we all chanted. Finally, he rolled over quickly to begin his dash away from the red missile monster. The rocket whizzed past him and he started on all fours to scramble away.

We didn’t see my mom on the porch, but did hear her shriek. She walked out just in time to see the rocket cleave open the top of Jay’s head as his timing wasn’t... quite right. I’m almost sure there wasn’t a thud of any kind, just a swish sound as the sharp rocket bottom performed a slicing scalp.

Bloody taxi ride to Dr. Feek, blood stained couch, blood stained towels, blood stained apron, bloody drips on the driveway — the bloody images all blur together. Jay’s injuries weren’t deep, just bloody, and required 20 stitches to close. The incredible sympathy and mounds of ice cream he got wasn’t excessive, we three brothers thought, but homage equal to his injury. The bald spot on his head was his great badge of honor. We hoped, secretly, that his hair would never grow back and the stitches would stay and we’d end up with a cousin with a Frankenstein scalp.

When we woke up the next morning, the day after the second best witness injury ever, eclipsing even my face first full speed bike wreck in the gravel, (nothing would ever beat Roger’s severed finger), we sensed the rocket was doomed. We looked out the kitchen window and saw the rocket forlornly protruding out the back of my dad’s Bel Aire station wagon, heading for the gloom of the dump. Hauled off to the land fill, the thrill of that summer ended.

About the Author