How do you say enough in praise of King Cole? More than any other person during the past half-century, he made Spokane the place it is today. Our beautiful Riverfront Park, vibrant downtown, exciting sporting events and excellent restaurants — all of these attractions and more grew either directly or indirectly from King Cole's influence.

When he came to town in 1963, this was a rather dingy city beset by urban blight. But when Cole died a few days ago, on Dec. 19, 2010, Spokane had become the sort of city that could attract one of the premier sporting events in America, the U.S. Figure Skating Championships, twice in four years.

By any measure, Spokane in the 21st century has a lot of mojo for a city its size. But would the city be where it is today if a young urban planner from San Leandro, California, had not accepted a job offer from a group of local citizens in 1963? These boosters' hearts were in the right place: They wanted to rescue Spokane Falls from decades of exploitation.

At one time, the "conquest" of the falls made sense. To the city's 19th-century founders, the rapids were there to run sawmills and grist mills and, later on, to generate electricity. The falls area also provided a dandy spot for railroad terminals, parking lots and an industrial laundry. Cole became the catalyst in Spokane for those with a new vision for the city and its falls.

A few years ago, while working on a book about Spokane and Expo '74, I had the privilege of interviewing Cole many times, reliving with him the story of Spokane's transformation.

On the role of an urban planner, he told me: "Everybody wants to do something, and everybody gets excited and discouraged and upset, but in the last analysis, at the end of the day, you find out that nothing gets done unless there's one person who lives and breathes and eats the problem day and night... so you have to hire your worrier."

Cole was hired to be the "worrier" for Spokane. And worry he did, month after month, year after year. He gave talks to scores of civic groups, traveled to Olympia, and Washington, D.C., and eventually around the world on behalf of Spokane's renaissance. Those who remembered Cole during the fair-building praised his persistence. "He wouldn't let it die," I was told.

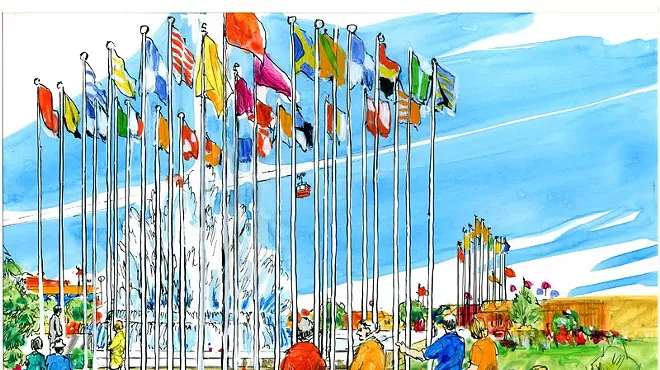

He led Spokane in building Expo '74, which made possible the urban renewal sought by him and others. His effectiveness drew on his own passionate commitment to beautifying Spokane. One of his favorite memories was his first view of the downtown without the wall of tracks that had separated the city from its falls. Cole remembered: "The day that I actually drove down, and they weren't there, I felt like, if nothing happens, if the fair didn't happen, if I died, whatever happened, what I really wanted to do the most of all was to get rid of those damn tracks!"

My interviews with Cole came about 20 years after Expo '74. Retired by then, he was philosophical about his work in Spokane. "When I was young," he said, "I used to love to take bows. I'd work my buns off to get some project going and, in some cases, put in a huge percentage of the energy and creativity, and then no credit — boy it hurt! But when you get older, you find out that what's important for the future is that the job gets done."

The urban renewal job in Spokane did get done remarkably well, first with the world's fair, then the transformation of the fair site into one of the loveliest downtown parks in any American city, and subsequently in the ongoing development of Spokane.

In 1994, on the 20th anniversary of the fair, three mayors of Spokane spoke at an event in his honor. Former mayor David Rodgers said King Cole had been the "stem-winder," the one essential person in Spokane's rebirth. Rodgers's mayoral predecessor, Neal Fosseen struck a personal note: "I don't know of a finer, more honest, more caring person than King Cole," he said. And the then-current mayor, Jack Geraghty, himself an Expo employee, noted that Cole was the greatest visionary and statesman the city had ever known. Geraghty declared there are few charmed moments in the history of a community when the people share a common vision: The era of the world's fair was one such time for Spokane, and King Cole provided the vision.

During one of our meetings, Cole told me he thought of his life as being like a rock thrown into water. "The water all sloshes back, runs back and forth and bubbles, and makes a bunch of waves, and they get smaller, smaller, smaller, smaller." As he continued, Cole was whispering. "Pretty soon," he said, "it's perfectly calm, like nothing ever happened. That's what life is like."

The sentiment is profound. And yet, of course, in King Cole's case, something — something very big — did happen.

So the next time you see children playing in Riverfront Park, or feel the spray of the falls from one of the footbridges, or ride the carousel, or watch the sun setting over the frame of the U.S. Pavilion — experience, in short, the beauty of Spokane's downtown heart, think of our own King Cole. ♦

King Cole died at the age of 88 on Dec. 19, 2010. Bill Youngs is the author of The Fair and the Falls, now out in a new, updated 50th anniversary edition.