In 2000, artist Nicholas Sironka and his wife moved to America for opportunity, like the many millions of immigrants who came before them. They traveled more than 8,800 miles from a small, hot town just south of Nairobi, Kenya, to Spokane, sending money home to their young children staying with family, fueled by high hopes and little to fall back on if things didn't pan out.

But for all the elements of the "stereotypical" American dream in Sironka's story, his goal didn't stop with earning enough money to send his kids to school or becoming a successful artist to support his family. This opportunity was something bigger, something he couldn't give up on: his best chance on one of the biggest stages in the world — America — to finally paint a truer picture of the 400,000 Maasai people in Kenya than the misrepresentations he'd seen all his life.

"I remember walking down the streets [of Nairobi] to buy [art] materials and going past the curio shops," Sironka, 49, says. "And I would see images of Maasai men and women kissing or holding hands, and American tourists buying them or stopping to look at them."

That made no sense, Sironka says, because Maasai marriages are often arranged, and there isn't much courtship or public display of intimacy. For a recent example, he points to Mindy Budgor, a white Jewish American woman, who in 2013 claimed to be the "first female Maasai warrior," which is not possible within authentic Maasai culture (and whom many Africans, like Maasai woman Esianoi Pashile, subsequently schooled in several articles).

"Then I thought to myself that instead of complaining, I should correct this and tell the true story," Sironka says. "I was always fascinated by the beauty of my culture, but I didn't have an inclination of how I could represent it to the world, but I would always sketch things."

Though he didn't grow up in a traditional Maasai village — instead, privileged to get a good education in the city and learn English because of his German stepfather's financial support — his mother raised him and his siblings to speak Maa, the language of the Maasai (which means "people who speak Maa").

Learning his ethnic language gave Sironka an all-access pass to study the songs and literature of his people. Growing up, he'd always visit his grandmother's village during school breaks, when he'd interview elders about Maasai myths and have the cultural experiences that color his canvas today.

By the late '90s, Sironka had become a prolific, dedicated artist and cultural representative painting vivid scenes of Maasai life using a nontraditional art form, batik — a time-consuming technique thought to originate in Indonesia, in which hot wax is applied to portions of the painting so that the canvas "resists" the dyes added later on.

That passion and hard work made Sironka's home a can't-miss stop for more than 100 study-abroad students from the U.S. who did homestays in his and other homes in the village, including Molly Erb, a Whitworth University student who later invited Sironka to Spokane (and America, for the first time) for her wedding in 1999.

"My wife said, 'This is your opportunity!'" Sironka says. "She said, 'I know Molly will introduce you to other artists and professors at Whitworth.' I was scared I wouldn't get my visa — I didn't have a big sum of money to show that I was secure and would actually come back home."

But Sironka got more than a visa — he became Whitworth's first Fulbright scholar-in-residence, lecturing on Maasai culture and leading batik workshops in the 2000-01 school year through the efforts of Lynn Noland, director of Sponsored Programs, and art professor (and now close friend) Gordon Wilson.

"The scholar-in-residence program is usually for individuals with Ph.D.'s," Wilson says. "But we made a strong case for his cultural knowledge and his own personal research. And he received that scholarship as a result of what he can bring to our culture — it wouldn't be possible for me to go to Kenya and bring back what he does."

Sironka wasted no time. He became a permanent resident and started leading hundreds of batik and culture workshops at schools and universities across the U.S. In 2001, he returned to Kenya to form a traditional dancing and singing troupe with people in his village, bringing more than 80 dancers to tour America over the next eight years, and raising money for the dancers to build new homes and send their siblings and children to school. The dancers usually stay with kind homeowners in the city they visit, forming easy friendships and inspiring many people to give, like one woman who sold her car and sent the money home with the villagers during their 2005 stop in Maryland.

In 2001, Sironka also began a group called Plant A Tree and Change A Life, which raises money for 16-year-old Maasai girls — who would otherwise typically become young wives — to go to high school, and has since found sponsorships for more than 60 girls. He's also worked as an art therapist with children at Sacred Heart Medical Center.

Wilson, the art professor and his friend, says that what makes Sironka such a valuable cultural ambassador is his charisma and personality. He still remembers the first few times he'd call Sironka on the job just to remind him of something, and Sironka would start to laugh.

"I asked what was funny, and he said, 'Well, the first thing you do in our culture is ask how the goats are,'" Wilson says. "So usually when I call him and talk to him now, I ask him how the goats are first. It's not just about business with Sironka, it's about human interaction. He's always working to do good, and assist people when he can... it's hard not to want to be a part of it."

Sironka has embraced life and the people in America, but his wife Seleina's sudden passing in late 2013 shook him. He hasn't been to Kenya since her funeral, and grief sent him adrift for a few years — still working, but questioning his mission, and the strain it may have put on his wife living abroad. Seleina was the architect of his move to the U.S., however, so he knew she'd want him to continue.

"I remember filling out the 'widowed' box for the first time on some documents, how difficult it was," Sironka says. "But we say in my culture, 'Prosperity comes as one climbing a mountain.' It means you have to struggle to succeed; life doesn't come just so easy."

Lately, that's been especially true. A batik workshop he opened in North Spokane in mid-December is already closing due to financial struggles, and his teaching engagements have slowed. Now he's trying to reconcile the angry, fearful anti-immigration voices of the America he resides in today with the land of immigrants he was first welcomed to in 1999.

Even so, his work continues to open minds and start conversations. At his most recent exhibition (Feb. 23–March 27) at Eastern Washington University, Dianne Stradling Denenny and Charlotte Vandekamp, who had never heard of the Maasai or batik, read the stories beside Sironka's paintings and peered into the rich colors, emotions and ideas for just a few minutes before immediately sharing their reaction.

"Wow," Denneny says. "Cheney needs this. We need to see more of this — you know, the world. We've decided what we like the most about these [images] is the peace and the respect."

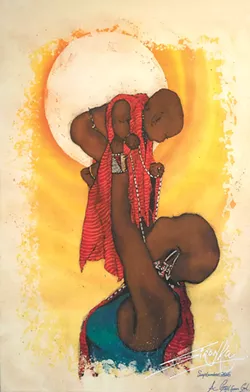

"You get so caught up," Vandekamp adds. "But then you see this — look at that baby [in Sironka's painting, "A Gift from God"], how cherished it is."

Now, Sironka is packing up his shop to return as artist-in-residence at the Hatch, a workspace for creatives in Spokane, and offer classes (often with a cup of Kenyan chai) at Spokane Arts Supply. He's working with a publisher on a book of his illustrations, and he's always got his eye on the next opportunity — this work is too important to stop.

"They say the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting the same result. I am not insane," he deadpans, then laughs. "I will try new things, and keep working hard. Giving up has no time frame." ♦

You can sign up for a batik workshop with Sironka (at northwestmuseum.org under "Adult Education" or "Calendar") taking place on Sat, March 4 at the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture.

Teens and tweens can also sign up for a two-part (attend either or both) batik quilt workshop at Spokane Valley Public Library (at scld.org/locations/spokane-valley under "Upcoming Events") on Sat, March 11 & 18.