Flamenco is known for its emotional intensity. On the surface you've got the gorgeous, dramatic ruffled train dresses (bata de cola) and fringe shawls that flamenco dancers throw around to create as much movement as possible. You've also got the use of lacy fans and castanets (little hand clackers) that are often used to punctuate every intricate step a dancer takes. Through each rotation of their body (giros) and expressive arm movement (braceo), a flamenco dancer can showcase love and joy just as easily as they can loss and pain.

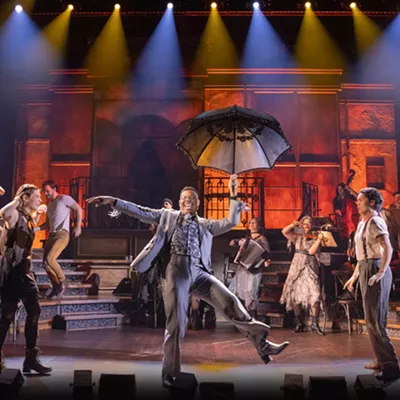

Beyond the glamour and drama, flamenco is a dance style with a rich cultural history. Since 2017 Monica Mota, founder and owner of Spokane-based dance company Quiero Flamenco, has trained local performers and brought in top-tier talent from across the country to showcase the art form in the Inland Northwest.

Flamenco was created in southern Spain, as early as the 15th century. The area at the time was inhabited by groups from many ethnic backgrounds, including Hasidic Jews, Moors and Romani people, Mota says, so flamenco came about in an effort to preserve the region's diverse culture.

"When you try to suppress cultures, you take away their language, you also take away their music," she explains. "Essentially, it's really hard to take away feet and hands, so clapping and footwork become that percussive line — the dancer is kind of like the drums. What came out of it was this art form melding together different genres of music and cultures."

On Friday, Spokane's Quiero Flamenco is sharing this cultural expression with the community at Gonzaga University's Myrtle Woldson Performing Arts Center for its annual show, Gradience. Alongside guest artists Jose Moreno, Jed Miley, Amelia Moore and Daniel Azcarate, the show features the musical direction of Spokane-based artist Mellad Abeid.

Local station KSPS-PBS also plans to air a taping of the performance on Feb. 14 at 8 pm.

Traditionally, flamenco is defined by its song, not its dance. Usually a singer takes the lead on stage and is followed by a guitarist whose work is to find the melody and harmonize with it. Once the dancer comes in, it's their job to connect with the music and improvise a performance.

These performances are often referred to as tablao, a Spanish word referring to the floorboards on which improvisational flamenco happens. Without strict choreography, a dancer must pull from their personal repertoire of steps to showcase years of technical training. Mota says tablao performances in flamenco are unlike anything else. About half of Gradience will include choreographed performances, while the latter part of the show will be improvised.

"I don't think people will even believe this is improv," she says with a chuckle.

This type of cultural performance isn't often seen in the Inland Northwest, or really anywhere else around the country, because there aren't many flamenco guitarists and singers. In total, Mota estimates that there are about five singers in the country skilled in flamenco.

"That's why I started teaching in the style of flamenco," she says. "I tell [my students], 'I'm teaching you steps, but learning the improv means that you need to learn the song, and you need to learn the guitar, not how to play it, but the rhythms that are coming out of it. As a dancer in flamenco, you're another musician.'"

Though there are more flamenco dancers than singers, Mota says it's still a rare skill to possess. (She still treks to Spain every year to train, ensuring her flamenco skills don't dull.) It took at least seven years of training for Mota to feel comfortable with one of her dancers performing a traditional flamenco tablao.

"My dancers work really hard, and they keep learning and growing, and now we're at a point where I have one student [Marlena Mizzoni] who can do the tablao section, and I have another one who's almost there," Mota says. "That's why I love my company, they've all been patient enough to realize that this takes time."

The scarcity of flamenco, alongside Mota's dedication to dance in the Inland Northwest, is why the team at KSPS-PBS decided to produce Gradience.

"Spokane is one of those places where we don't really support dance like a lot of other cities our size do," says Zana Morrow, arts and culture coordinator at KSPS. "[Mota] works so hard in the community to make sure that there's a voice and stage for these kinds of traditions in local dance."

As the show's producer, KSPS handles most of the funding, ticket sales, promotion, and even the documentation and archival of the performance through photos and video. This is the second time in as many years that the station has produced a show at this level. Around the holidays in 2023, KSPS partnered with the renowned ensemble Clarion Brass for another performance at Gonzaga.

"When you try to suppress cultures, you take away their language, you also take away their music,"

tweet this

"The vast majority of us grew up on PBS Kids, and whether we kept watching or not after childhood, most everyone knows how respected PBS is," Morrow says. "Having their [annual performance] archived by PBS is everything that they could want."

In past years, Quiero Flamenco's annual show required Mota to coordinate most of that work. This time, because of KSPS' investment, she gets to focus most of her energy on crafting her personal artistic vision. For the nonprofit broadcast station, producing Gradience supports the artistic vision it seeks to cultivate in the Inland Northwest.

"We're trying to raise the bar and make sure that we're taking chances on people that are just providing something that is above-grade art, and not just people who are really good at selling a ticket," Morrow says.

"This is a real, large, beautiful part of our community, and they deserve to be recognized," she continues. "It's going to be a beautiful night, just absolutely breathtaking." ♦

Quiero Flamenco Presents: Gradience • Fri, Jan. 10 from 7-9 pm • $35 • Myrtle Woldson Performing Arts Center • 211 E. Desmet Ave. • quieroflamenco.com