Spokane's skyline boasts three iconic buildings.

The Pavilion. Gifted to the city by the United States government in preparation for Expo '74, the cable structure is unlike any other in Spokane.

The Great Northern Clock Tower. Constructed in 1902, it's a reminder of the beginnings of our city's history as a regional distribution hub in the early 1900s and, in many ways, feels like a beacon that draws people into the heart of our city.

The third building is a parking garage. Yes, a parking garage.

The Parkade Plaza, or simply the Parkade to locals, is an 11-story concrete building in the heart of downtown Spokane.

Though the parking garage is taken for granted by many of us today, the building was considered a major success after its completion in 1967 thanks to Spokane-born architect Warren Heylman.

From the top floor of the Parkade, you can see Heylman's impact on Spokane. Riverfalls Tower. The Latah Creek Viaduct. The Bennett Block he helped restore. The Spokane Regional Health Building — Heylman's most controversial project — and the Spokane International Airport, which he designed in partnership with William Trogdon.

Along with Heylman and Trogdon, a host of active, modernist architects made Spokane their home in the mid- to late 20th century, bestowing the city with an impressive collection of midcentury modern commercial buildings, like the Avista headquarters on Mission Avenue, the lemon-lime Shadle Park reservoir, downtown's Farm Credit Bank Building, a host of churches and many more.

What's lesser known — and less appreciated — is Spokane's cache of midcentury modern residences.

Primarily concentrated on Spokane's lower South Hill and in the Cliff-Cannon neighborhood, these homes are prime examples of the talent that came out of this modernist boom. With their clean lines, use of natural materials, flat roofs and vast expanses of glass, these homes are architectural gems hidden at the end of tree-lined streets and behind dense foliage.

In a city like Spokane — better known for its craftsman bungalows built primarily between 1900 and 1930 — these low-to-the-ground midcentury dwellings can get lost in a sea of older homes. Yet, in the past 15 years or so, midcentury buildings have become better appreciated by a growing number of architecture enthusiasts and those who have gotten over their distaste for the design of the past.

At the same time, midcentury homes and buildings are still being torn down in favor of newly built homes.

In 2018, Spokane lost two of these architect-designed, midcentury homes to demolition. One was designed in 1953 by Heylman for his friend, businessman John Hieber, the two men responsible for the Parkade years later. The other was designed in 1965 by Ronald Sims, lead architect of the Spokane Veterans Memorial Arena, for J. Birney Blair, a prominent television adman who would later become president of KHQ. Both homes sat on the edge of the Manito Golf and Country Club.

Because neither home was listed on any local or national historical register, they had no protection against demolition. Yet, even if they were listed, not all historic registries guarantee protection.

People who own buildings on the National Register of Historic Places or state registers, for instance, can alter or demolish their properties as long as they follow local building regulations.

But in Spokane, we have the Spokane Register of Historic Places, which was established in the early 1980s. The countywide registry offers better protection against alteration and demolition — but still on a very minimal level. All proposed aesthetic changes to locally registered properties have to be approved by both the Spokane Historic Preservation Office and the Spokane Landmarks Commission.

For a home to be placed on the Spokane register, it must be associated with a historically important person, event, or era, or embody a certain type of architecture.

Megan Duvall, Spokane's historic preservation officer, acknowledges that early in her career, midcentury buildings weren't her thing — a blindspot shared by previous preservationists.

"In the '50s, people were looking back at the 1890s and 1900s buildings and saying, 'This is my parent's house. This is old, ugly and dusty,'" Duvall says. "I think we're at that stage now — and probably have been for the past 15 to 20 years — where people are looking at stuff built in the '50s, '60s and '70s and thinking it's old and uncool because it's stuff they remember from their childhood. It's a cycle."

Midcentury modern buildings were the ugly ducklings of historic preservation. But now, as the design style becomes popular again, they're being added to local and national historic registers.

Just this past November, Heylman's concrete wonder — the Parkade — was added to the Spokane register. The building, according to its nomination documents, "was constructed in a period of change and challenge to Spokane" and "gracefully conveys a movement to the future."

It's now time to preserve the homes built during this era, if just to save the story of Spokane.

"These houses serve as the story behind the architects that were here," Duvall says. "It's not obvious to people, or even the homeowners, why the homes are considered historic. We've got to bridge that gap because that is when they will realize that these homes are worthwhile."

During the post-war modernist boom, Spokane was ripe with architectural opportunities. Royal McClure, Kenneth Brooks, Warren Heylman and Bruce Walker all saw it and decided to leave their mark on the city. The homes they designed deserve to be remembered, preserved and treated with as much care as was given to them by the architects who created them decades ago.

They may just look like houses, one of thousands and thousands in Spokane. But if you take the time to understand, their story unfolds before your eyes. ♦

Norman E. & Dorothy Wells House

2020 E. 18th Ave.

ARCHITECT: Warren Heylman

YEAR BUILT: 1954

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Geometric design, vertical windows and the use of natural materials

SIDENOTE: This home has been a part of many historic tours in the area, including the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture's Mother's Day Home Tour in 2013 and a tour of mid-20th century properties in Spokane sponsored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2012. The house was chosen by the Spokane chapter of the American Institute of Architects for the Outstanding Architecture Award in 1960, and the home's owners, Norman and Dorothy Wells, received special recognition from the chapter's Design Recognition Program in 1977.

A key piece of midcentury architecture was bringing the outdoors inside, and it seems like an extremely apt design concept for Spokane given the city's proximity to nature and continuing love affair with the ideas and relics from the environmentally themed Expo '74.

Decidedly Frank Lloyd Wright-ian, the Wells House deviates from architect Warren Heylman's usual neo-expressionist design characterized by curving forms and unusual roofs — best represented at the Spokane International Airport and the Liberty Lake Golf Course clubhouse. This house is muted in comparison to Heylman's other residential work and more in line with the philosophy of bringing the outside in by incorporating natural elements on the property into the home design.

Completed in 1954, the house was built for Norman and Dorothy Wells. Dorothy died in 1969. Norman, an executive at Old National Bank, remarried and moved to Walla Walla in 1989. The house had a few different owners until 2004, when Pat Smith and Kathryn Odorizzi purchased it.

In a May 2013 Spokesman-Review article, Heylman visited the home, almost 60 years after its completion. "I feel very good coming back to this house. So often you come back and you don't even recognize the house you built, but you've done a great job here," he said about the homeowners, Smith and Odorizzi, who lived in the home until 2019.

A history of the home, compiled by local preservationist Diana Painter and Aaron Bragg for their Spokane Mid-20th Century Architectural Survey Report, compares it to Wright's Usonian period when the architect attempted to design "liveable, typically small houses tailored to their owners' needs." Heylman certainly channeled Wright in that sense as Usonian-style homes typically have large, vertical windows with flat roofs and cantilevered overhangs, all of which are present in the Wells House.

Heylman is best known for his large-scale public projects, so it may come as a surprise that he also designed and built over 20 midcentury homes during his 40-year career in Spokane. In fact, he lived in dwellings of his own design for most of his life — nearly 65 years in his red-roofed home near Indian Canyon Golf Course, and then, in their 90s, he and his wife moved into a condo in Riverfalls Tower until his death in 2022.

But the Wells House stands out among his portfolio of residential projects for its understated charm and timeless design.

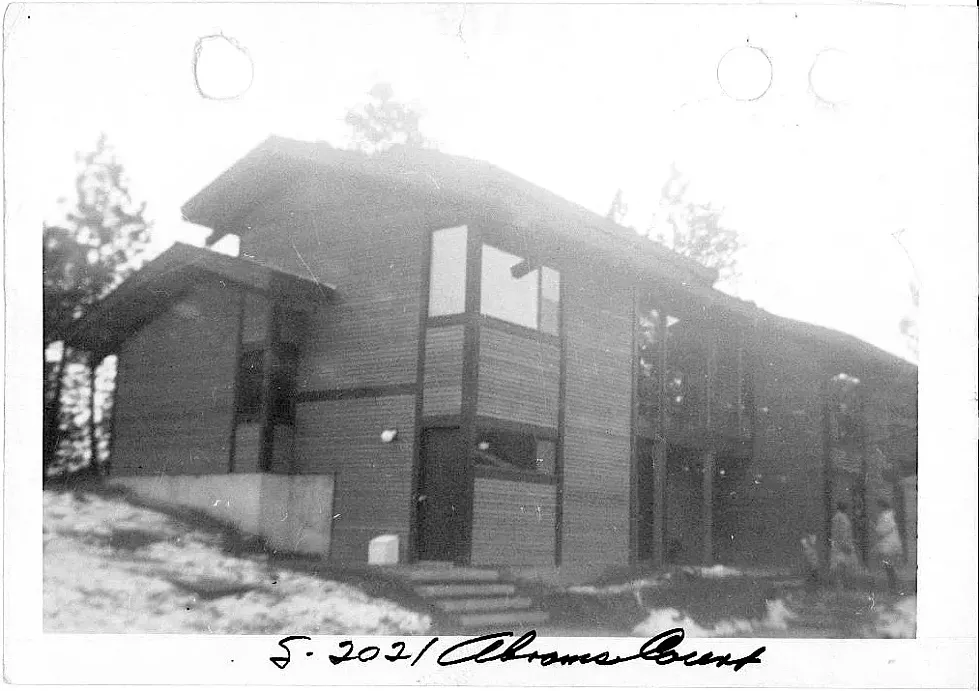

Anderson House

2021 S. Abrams Court

ARCHITECT: Bruce Walker

YEAR BUILT: 1965

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Use of wood inside and outside, extended rooflines, geometric design

SIDENOTE: When architect Bruce Walker was just 28, he won a national design contest co-sponsored by the magazines Architectural Forum and Building, as well as the National Association of Home Builders.

The original cost of the Anderson House was $55,000.

Last year, it sold for $1.2 million.

The home is tucked away near the end of a cul-de-sac in the Rockwood neighborhood. From the street it's unassuming, but it's quite the treat for any architecture nerd who may stumble upon it, including its new owners, John and Beth Harker.

"When I walked into that house for the first time I just knew," John says. "I knew I never wanted to leave."

The couple specifically sought out a midcentury, architect-designed home when they moved to Spokane from California. (Their Realtor, Marc Nilson of Navigator Northwest Real Estate, has focused on selling midcentury homes.)

The home was originally built for Ted and Judith Anderson, who became good friends with architect Bruce Walker when they moved from Seattle to the east side of the state.

In a video made for the home's sale last year, Judith describes the home as "wide open" and "lodge-like." She continued: "I wanted the home to have Spokane elements. ... The basalt, the brick and the cedar wood."

The interior of the home mirrors the exterior, each of which features either cedar paneling and siding that's gone untouched for almost 60 years.

From the outside, the house looks almost Craftsman-like, with triangular gables and painted trim. But vast expanses of glass and post-and-beam-style windows give the home that quintessential midcentury feel.

"Our house is a piece of Spokane's history," says Beth, the new owner. "We are stewards to this home now and with that comes major responsibility to honor that house for what it's supposed to be. ... Anything we touch, we seek to retain the original integrity."

The Harkers are still updating the kitchen and other parts of the house, and have yet to move in. They've thought about placing the home on a historic register, but haven't decided.

Walker was born and raised in Spokane. He left home for the first time in 1941 to get his bachelor's in architecture from the University of Washington, but his education was disrupted when he was drafted into the Navy. After completing his military service in 1947, Walker went straight back to school and finished his degree.

Soon after moving home and gaining experience with a few local firms, including the famous and well-regarded McClure & Adkison, Walker went to Harvard and studied under Walter Gropius, the German-American architect and founder of the Bauhaus school who is regarded as one of the founders of modernist architecture. After a brief stint in Europe, Walker returned to Spokane in 1952.

His best-known projects include the Temple Beth Shalom, the Joel E. Ferris House, the Spokane Opera House & Convention Center (now called the First Interstate Center for the Arts) and the granite- and glass-faced Farm Credit Bank building on West First Avenue in downtown Spokane.

Frank Toribara Residence

1116 S. McClellan St.

ARCHITECT: Frank Toribara

YEAR BUILT: 1960

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Asymmetrical form, post-and-beam design and window walls

SIDENOTE: Frank Toribara and his wife, Ruth, were forcibly relocated and incarcerated at the Japanese internment camp Minidoka in Jerome, Idaho. Like the vast majority of the 125,000 people of Japanese descent who were detained in U.S. concentration camps during World War II, Toribara was an innocent U.S. citizen facing the racist policies of a nation at war.

Residing just outside the boundary of the Marycliff-Cliff Park National Historic District on Spokane's lower South Hill, this midcentury residence was designed by local Japanese American architect Frank Toribara.

The home was designed in the contemporary style, defined by having fewer stylistic details, allowing the simple form and clean-lined design of the home to speak for itself — elements present throughout most of Toribara's residential and commercial work.

Highlights of the home's facade include an elongated entryway and a gently sloping roof that define the main form of the home.

The home also features a cluster of angular clerestory windows. A clerestory is a high section of wall that contains windows situated above eye level. Many midcentury architects used these to let air and light into a room — another way to bring nature inside through design.

The home stands out among those that surround it, thanks to Toribara's unique Asian-influenced touches, such as the vertical siding and a garden attached to the entryway. The detached garage seamlessly flows into the home, as if it was not detached at all, serving as an ode to Toribara's sensitive and careful planning.

The home underwent remodeling in 2010, but has retained its '60s charm and remains a prime example of Spokane's many Toribara-designed residential homes.

Toribara was born in 1915 and received his architectural degree from the University of Washington in 1938. For five years after graduation, he worked as a draftsman for Seattle architect James M. Taylor.

According to the UW's archives, Toribara received his architectural license 13 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Soon after, he was incarcerated at the Minidoka internment camp in Idaho. After leaving Minidoka, Toribara and his wife moved to Spokane, and Toribara resumed his career.

During his lifetime, Toribara designed a plethora of commercial buildings in Spokane, including the Highland Park United Methodist Church, the Tombari Dental Clinic, and the former Farmers and Merchants Bank building. He was also involved in the design of the Garland Theater as well as the Japanese Pavilion for Expo '74.

Toribara died in 2007, just as the buildings he designed in Spokane began to approach their 50th birthdays, and thus became eligible for protection. Now, the buildings and homes are beginning to be placed on the local register.

The owners of one of Toribara's homes, the Louis and Ruth Farline House (1953), successfully listed it on the local historic register in 2016. In March 2023 the Highland Park United Methodist Church was placed on the Spokane Historic Register.

Those are just the beginning. Toribara's impressive career spanned more than 50 years, and his impact on Spokane is still being felt and recognized.

Murray House

611 W. Sumner Ave.

ARCHITECT: Donald Murray

YEAR BUILT: 1965

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Asymmetry, use of concrete and angular roofline

SIDENOTE: The Murray House features embellishments designed by Spokane artist Harold Balazs.

|t's easy to miss the Murray House, buried in foliage and surrounded by an ominous stone wall. But once you see it, you'll never forget it.

Looking like something out of a sci-fi movie, this shed-style home was designed by Donald Murray, a Walla Walla-born architect, as his personal residence. The unique shingled peak in the middle of the roof is the obvious defining feature of the home.

Shed-style buildings are defined by their oft-recessed entryways, angular roofs and attention to energy conservation with their passive-solar design elements including south-facing clerestory windows, rock walls and more. The style was most popular in the '80s; a commercial strip mall on South Grand Boulevard (home to Allie's Vegan Pizzeria & Cafe and the UPS Store, among others) boasts a similar design.

The Murray House is unique in the sense that it's built out of concrete blocks rather than wood like most houses on this list. Concrete was a popular material in midcentury design, but it was used more often in commercial construction than in residences. Though the home is made of concrete, it doesn't feel sterile or cold. It's inviting, tucked away behind bushes and trees, almost beckoning pedestrians to stop and stare for a moment.

In 1982, the Murray House was almost a goner.

The Spokesman-Review reported that 13 firefighters fought an electrical fire and "flames burned the attic, roof and inside walls of the house." Almost certainly, the use of concrete in the structure prevented further damage.

The home resides in the Marycliff-Cliff Park National Historic District but is a non-contributing building since it was built outside the district's historically recognized period of development (1889-1941). This gives it little to no real protection from alterations or demolition, but the home's owners have kept the structure sound, and it hasn't been significantly altered from its original state.

Like many of Spokane's noted modernist architects, Murray received his architecture degree and then went straight into service — on the Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams, where he was awarded the Silver Star Medal for his valor.

In 1946, Murray found himself in Spokane working at Funk, Molander & Johnson. In 1957, he became a partner, and the firm changed its name to Funk, Murray & Johnson. In 1974 he opened his own firm.

He designed buildings for WSU (his alma mater), Gonzaga University, IBM, and the federal government. He retired in 1982 and died in 2004.

Will Apartment House

358 S. Coeur d'Alene St.

ARCHITECT: Richard E. Will

YEAR BUILT: 1964

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Modular form, use of concrete and geometric shapes

SIDENOTE: Even though the Will Apartments are in the Browne's Addition Local Historic District, the building has no protections. The historic district only recognizes structures built before 1950.

Now known as the Canyon View Apartments, this low-rise multifamily dwelling has nine residential units and offers incredible views of the Latah Creek Valley and its three tall bridges from its position on the southwest edge of Browne's Addition.

Richard Will designed the Will Apartment House in the International style, which is known for its clean geometric simplicity and rejection of ornamentation. The movement was pioneered by noted architects like Walter Gropius and Florence Knoll.

This style cropped up in Europe first before heading to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City for the 1932 exhibition titled "The International Style: Architecture since 1922."

Even though the style of building was introduced to the U.S. before World War II, the design didn't become popular until after the war.

The apartment building's facade is devoid of aesthetic ornamentation beyond the canopy at the entrance, which was added after its initial construction. The ribbon windows form a continuous horizontal band around the facade, emphasizing the rectangular geometry of the building and creating a symmetrical design.

Along with the Studio Apartments (1102 W. Sixth Ave., designed by Bruce Walker, when he worked for McClure & Adkison), the Will Apartment House is an excellent example of a modernist, low-rise apartment building.

Although Will designed many Spokane apartment buildings after opening his own practice in 1964, he may be best known for the Backlund House in the Rockwood neighborhood.

Fischer House

1618 E. Pinecrest Road

ARCHITECT: Richard Neutra

YEAR BUILT: 1951

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Horizontal emphasis, use of natural materials and flat roofline

SIDENOTE: Architect Richard Neutra was not from Spokane, but he was mentioned on The Simpsons in 2012!

|n his life, Richard Neutra was just about as far removed from Spokane as possible, yet we're lucky enough to have a small piece of his legacy within city limits.

In August 1949, the Vienna-born architect appeared on the cover of Time magazine with the headline "Architect Richard Neutra: What will the neighbors think?" Two years later, Dr. Frederick Fischer and his wife, Cecel, commissioned Neutra to design their home in Spokane.

The home, which sits on the southeast edge of the Rockwood neighborhood, is an early example of modernism in Spokane with its vertical wood siding, ribbon windows and minimal decoration to the home's exterior.

Before visiting the Pacific Northwest to design the Fischer home — as well as a residence in nearby Missoula — Neutra was celebrated in California, where he was most prolific, for his rigorously geometric structures that served as a West Coast variation on the midcentury modern residence. Examples of Neutra's early style include Palm Springs' Kaufmann Desert House and the Lovell Health House in Los Angeles.

The Fischer house has a much more raw, natural feeling to it than his previous work in California, donning wood siding rather than the stucco finish typical of his homes.

Neutra was also known for the attention he gave to his clients. According to a 1954 Spokesman-Review article, the Fischers gave him a simple instruction: "Build us a home around music and a fireplace." Neutra "gave them that and much more. It's a place for their music — piano, organ and phonograph — their grandchildren... their books and paintings and their friends."

Like many midcentury modern houses, the Fischer house presents a very private appearance, with dark, vertical wood siding under expanses of ribbon windows and a stone pathway leading visitors to the front door.

Neutra died in 1970.

Gordon & Jane Cornelius House

3717 E. 17th Ave.

ARCHITECT: Royal McClure and Thomas Adkison

YEAR BUILT: 1951

WHAT MAKES IT MODERN: Neutral color palette with pops of color; clean, straight lines; and asymmetry

SIDENOTE: Current owner Andrew Wolfe purchased the home from Jane Cornelius in 2018. Wolfe and his family has a long history with midcentury architecture in Spokane — his grandparents as well as his parents lived in Bruce Walker-designed homes. He lived in a Walker home on 14th Avenue for many years, but says it was severely damaged by a fire in 2017. "Now it's lost forever," Wolfe says. "These homes are an essential part of our city's history, I wish more people would appreciate them."

Some of the best things in life are born out of teamwork.

The Cornelius house in Spokane's Lincoln Heights neighborhood is a prime example of early modernist architecture with its boxy, geometric design. But it also represents the legacy of one of the greatest architectural partnerships in Spokane.

Architects Royal McClure and Thomas Adkison were both Pacific Northwest natives. The two graduated from UW and quickly formed a partnership that lasted 20 years.

This home was designed in the Contemporary style, meaning that it differed slightly from the ranch-style homes of the era. Instead of horizontal emphasis, the Cornelius house is a high-style house with a flat roof and natural elements throughout.

The front of the home is composed almost entirely of glass. The windows are square and appear to be randomly scattered over the front and back sides, giving the home a distinctive look and decidedly retro feel. It seamlessly blends the natural elements of wood and glass together to create a cohesive building, something McClure and Adkison did well during their careers.

Along with many midcentury single-family homes, the pair worked on the Studio Apartments, the John F. Kennedy Pavilion on Gonzaga's campus, Joel E. Ferris High School and the Stephan Dental Clinic on West Indiana Avenue, which is one of the earliest examples of modern architecture in Spokane. One of their most well-known commissions is the design of Spokane's Thomas S. Foley U.S. Courthouse, the Parkade-reminiscent structure that represents the federal government but was designed by Spokane architects and built by Spokane laborers.

The architects' firm, McClure & Adkison, left behind a large collection of midcentury buildings, residential or otherwise, for Spokanites to appreciate daily. The Cornelius house, though tucked away from their other major projects, shines brightly among them. ♦