Like many Americans, Susan Polis Schutz found herself at her breakfast table many mornings over the past few years, shocked at what she was reading in her newspaper.

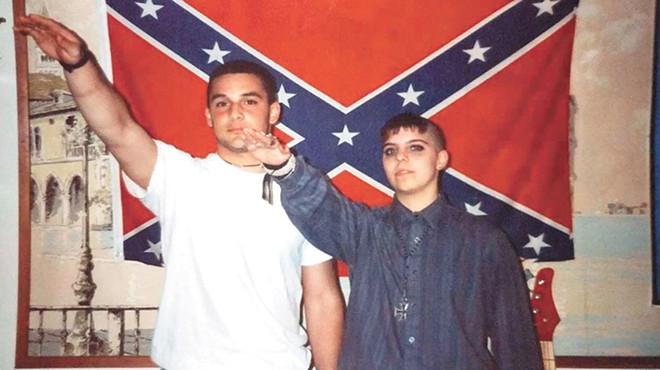

Violent crimes based on racial animus. Massive rallies of Nazi-saluting, khaki-clad "patriots." Statements from the highest levels of U.S. government ranging from outright racist diatribes to subtle nods to believers in White supremacy.

As a writer and what she terms a "socially conscious filmmaker," Schutz finally reached a level of sadness, confusion and concern that she only knows how to address one way — by turning her camera on.

At first, she interviewed people still involved in hate groups, prejudiced against certain races and religions, and she was frustrated at her subjects' lack of understanding of how their beliefs could be considered "hateful."

"Then I read an article about one of the guys I'd interview [later], and he was now an ex-White supremacist and he'd completely changed," Schutz says from her Colorado home. "Now he's helping people get out of the White supremacy movement, or just helping people overcome pain. I thought that was incredible. And I thought, 'Well, maybe I can talk to him and see if there's a reason he changed, and how he changed.'"

That first five-hour sit-down with Arno Michaelis, former lead singer of hate-metal band Centurion and a founder of Wisconsin-based hate group the Northern Hammerskins, gave Schutz "so much insight" into both the world of organized hate and the community of former White supremacists working to extinguish hate in the states. She decided to focus her next documentary on the people who were once deeply involved in the hate movement, but have moved on and now work to help others escape.

The resulting film, Love Wins Over Hate, debuts locally on PBS Nov. 10, and dives deeply into the stories of six men and women who were sucked into White supremacist groups across the country, but found their way out, sometimes with the help of mentors like Michaelis, and sometimes just by coming to their senses on their own.

"I make a film so I can better understand," Schutz says. Her past films have addressed issues like homelessness, aging, anxiety and depression. "I kept interviewing these people, and I found how they changed, and it gave me hope that other people can change. I wanted the viewers to understand what hatred is, how horrible it is, even to the person who's the hater."

Schutz might not be the most natural person to delve into the hate movement — "I don't even know anybody that hates people," she says — but the best-selling author, mother of Colorado Gov. Jared Polis and award-winning filmmaker manages to get incredibly revealing and candid stories out of her subjects. "I was very, very scared about meeting [Michaelis]. I had to overcome my own prejudice. I don't know what I expected; a big thug who was going to attack me? But as you can see in the movie, every one of these people was so sensitive and empathetic."

Of course, that's not where their stories started.

For Chris Buckley, a childhood of being physically and sexually abused eventually led him, after a stint in the Army, to become a leader in the Georgia White Nights of the Ku Klux Klan.

For Shannon Foley Martinez, a childhood rape led her to a "hatred of everything," and made her an easy recruit into a violent White supremacist group as a teenager.

For Michaelis, it was a childhood dominated by his father's drinking problem. For Timothy Zaal, joining the White Aryan Resistance gave him a family that valued him more than his own. For Christian Picciolini, joining an Illinois hate group as a teenager was part of his search for "identity, community and purpose."

"Every single one of them had some type of dysfunctional family," Schutz says. "Now, that alone doesn't make you hate other people. But it was the one thing they all had in common, whether it was physical abuse or mental abuse. Most of them had been bullied when they were younger. Most of them felt they did not fit in anywhere. And most of them are confused and don't know what they're doing with their life."

In Love Wins Over Hate, they all discuss how White supremacist groups essentially preyed on their traumas and sold them on a hate-filled vision for their futures.

"We basically thought that we would be agents in the breakdown of society and that we would be fighting to build this Aryan White state," Martinez, a former neo-Nazi, explains in the film.

The film subjects' paths out of hate groups vary some, but nearly all were inspired by self-doubt, a sense that all they were being taught to believe about hating people was somehow off. For Michaelis, his depression despite literal "rock star status" in the hate movement led him to start questioning things, and when he became a father he knew he needed to change. For Zaal, the Holocaust denial prevalent in hate groups led him to realize they weren't dealing in facts, just bigotry. Picciolini says once he started questioning a few things about his hate community, he started questioning everything.

Michaelis ultimately helped Buckley leave the KKK and also become an anti-hate activist, and each of the subjects in Schutz's film are working to eradicate hate, albeit in different ways. Zaal is now an alcohol and drug counselor and consults with the Simon Wiesenthal Center, while Michaelis works with students through a group called Serve2Unite. Picciolini won an Emmy for producing an anti-hate advertising campaign. Hearing them tell their stories, from their violent pasts to hopeful futures free of hate, makes for an engrossing hourlong film.

"Their whole goal in life now is to help people change," Schutz says. "They'll do whatever it takes, and they are so honest about what happened in the movement." ♦

Love Wins Over Hate airs locally on Tuesday, Nov. 10, at 10 pm on KSPS, Channel 7.