Twenty years ago, on a fine summer’s morning in Spokane, I saw a pair of white butterflies spangling up and down a neighbor’s Ponderosa pine.

Nice — but as the summer wore on, I saw more and more of these butterflies.

By August, they were swirling around the local Ponderosas like light, highly localized flurries of snow. There didn’t seem to be a pattern; they traced trails as seemingly random as that of a drunk around a lamppost. A mating dance? I wondered. If it was, I had yet to see consummations (though these might not have been public events).

The butterflies weren’t too hard to catch — neighborhood kids grabbed them barehanded and everywhere left fingerprints dusty with wing powder. Wafer, the cat next door, caught them, though it was a waste of her stalker’s intelligence. One morning, I spied several butterflies seemingly asleep in the air between branches, and then noticed the spiderlines upon which they rested in peace.

My 18-month-old daughter, Emily, could catch them; usually she then fed them to Wafer. “Catch” became one of Emily’s words of the summer. She would take my hand and ask if we could go down to the garden to catch flowers. Her confidence grew. Soon, she wanted to catch the moon.

So I decided to take a few specimens. I examined each one carefully, then let it go. They had no smell, as far as I could tell. They made no sound, unless you counted a slight flutter-buffet against a cage of fingers.

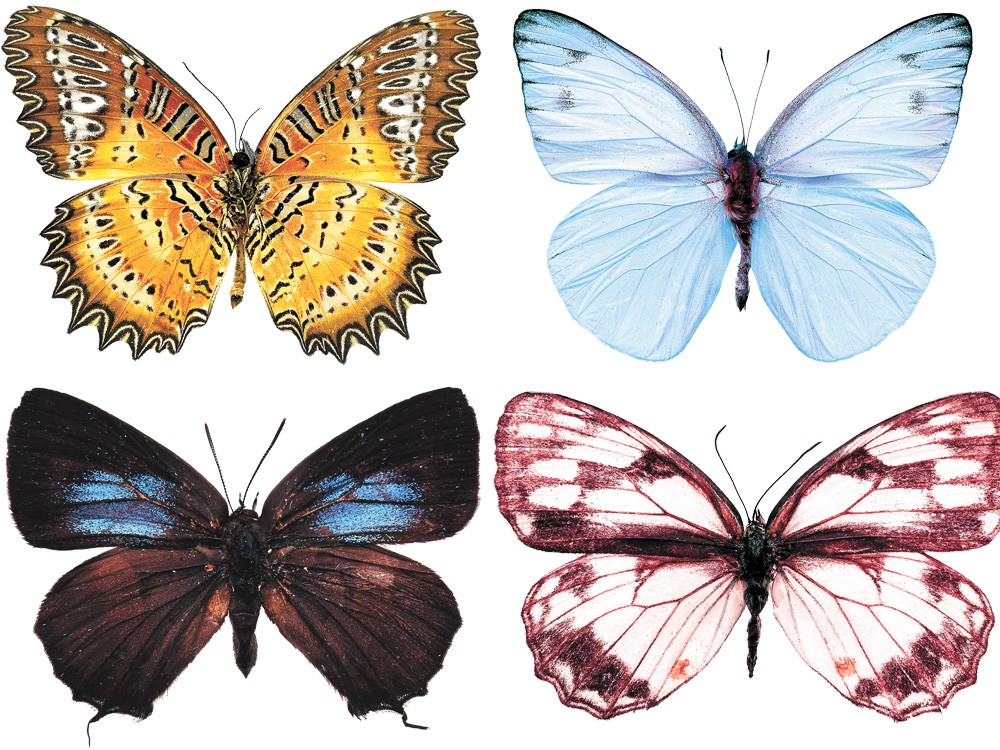

The wings were white, turning cream, with black markings. Their eyes were clear green beads, and I observed a curled-up strawlet of tongue.

Their abdomens seemed to come in two varieties, one rather withered, the other a bulging translucent green. The significance of this became clear one day when Emily squeezed a butterfly down my forearm as though it were a tube of toothpaste, laying out from the abdominal tip a wavy line of eggs much the size and shape of their eyes, though a paler, more glistening green.

So they had been mating, earlier. And having mated, they still spangled up and down. It’s what they did, this particular breed.

As the season tipped down from high summer, there was a noticeable decline in the butterflies’ condition. They were even easier to catch, exhausted, shredded, slovenly as dying salmon. We found them skewered on pine needles as if on collectors’ pins. Fragile wings littered the grass.

Their behavior deteriorated, also. At first, they’d maintained the purity of Ponderosa, but now they were branching out promiscuously, paying favor to lodgepole, cozying up to spruce, even to maple and magnolia. One dissolute butterfly, who’d apparently skipped a few Protective Coloration classes, laid her line of green pearls down the edge of a magenta washcloth on our clothesline.

Eventually I found my way to a library, and found a name: Neophasia menapia. The pine butterfly. The caterpillars eat pine needles, sometimes causing serious damage.

Reading further, I felt an almost personal chagrin when the text called N. menapia “a very primitive butterfly.”

I called the WSU County Extension Service and talked to the master gardener. She told me that, yes, we were seeing a large number of pine butterflies, an outbreak in fact. (Usually, the population is considered a problem when the average hits 24 butterflies per tree.) The master gardener said that something undoubtedly eats the butterflies, or their caterpillars, bringing them back into balance, but she didn’t know what. She said this was a mystery of nature.

Now there’s a resonant phrase, I said to myself, hanging up the phone. I could see from my kitchen window that for all their bedraggled glimmer, the butterflies were still maypoling around pine trees by the hundreds.

But we survived that summer, 20 years ago. Our pine trees are OK.

So why am I bringing this up now? Well, the pine butterflies may be coming back. Last summer, outbreaks of pine butterflies were reported in the Boise National Forest, in the Bitterroot Valley in Montana, and in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. They may be homing in on us.

I called the Master Gardeners again recently, and they told me that things seemed to be going OK so far in Spokane, on the pine butterfly front.

However … In old alien invasion movies, after the threat had been destroyed, as the love interests embraced, as the music swelled and strained, there was often a warning by a science guy: “Tell the world, tell everyone … keep watching the skies.”

Or at least the trees.