I was in middle-of-nowhere Holland when a Dutchman praised Spokane.

Specifically, I was in Linden, a suburb of Cuijk, itself in the hinterlands of Nijmegen, the 10th-largest city in the Netherlands, when Sjors van Duren began interrogating me about my origins.

"The U.S.," I said.

"Yes," said van Duren, an internationally known bicycle planner. "Where?"

"West Coast."

"Yes, where?" he said, his impatience with my generalities building.

"Washington state," I said. "Not D.C."

"Yes, yes," he said.

"Spokane."

Recognition hit his face. "Lovely city," he said. "I've been. There's a very cool bar by the railroad tracks."

He grabbed his phone from his pocket. "Steel Barrel," he said. "Oh, it's closed." (The location is now home to Golden Handle Brewing Co.)

From there we were off. He praised Spokane's beauty and suitability for bicycling infrastructure. We got on our bicycles, and spoke more as we rode on the many things he's brought to the Nijmegen region since beginning his career in 2008. The Fietsbrug Mook, a bicycle bridge over the Meuse River. The bicycle highway that takes commuters from the small towns in the Dutch countryside to the city's university, historic center and the stadium in Goffertpark, where this weekend the German metal band Rammstein would play to 50,000 people two nights in a row, many of them pedaling to see the theatrical, pyrotechnical mayhem.

Not me. I was on a monthlong tour of Denmark and the Netherlands this summer, studying bicycle planning and culture, meeting experts and advocates, and generally having my mind blown wide open to the possibilities of urban cycling. It wasn't my first trip abroad on two wheels. In recent years, I've ridden bikes on four continents — in Europe, Asia, South America and all over North America.

On nearly every street and bike path, and in every town and city I visited, I thought, "Could this work in Spokane?" More often than not, the answer: Definitely.

Clearly, there are hurdles, beginning with the financial advantages our government doles out to automobiles and roadbuilding, a fact on display in this year's Inflation Reduction Act, the single-largest climate policy investment in U.S. history that has not one single mention of bikes or transit, but shovels gobs of money toward electric cars. And in last year's infrastructure act, which invests a record $1.4 billion in "alternative transportation," a number swamped by the $350 billion going to highways.

Still, there are ways to transform Spokane's urban transportation system into one of green simplicity, where commuters won't find themselves stopped in traffic on the Monroe Street Bridge or Interstate 90, but flowing like water on two wheels. Where everyone feels safe riding, including children, and knows they can get where they need to go, and with little effort.

But how? Here are five ways we can make Spokane one of the best cities in the world for people on bikes.

BIKE HIGHWAYS

As van Duren and I rode into Nijmegen, we rolled through forests and pastures. We went over canals and under commuter rail lines. When we did cross the occasional road, drivers yielded.

We were on one piece of infrastructure that van Duren had helped bring to his hometown: an unimpeded bike highway.

At least that's what we call it in English, but its Dutch name — doorfietsroute — suggests its true purpose. It means the "keep cycling" route. The word "highway" suggests speed. The Dutch moniker doesn't. It's a matter of convenience, rather than pace.

I don't know what I was expecting when I heard I was going to ride on a bike highway. Maybe a Tour de France-style peloton of close proximity and racing speed. Not this. This, I said aloud to myself from the saddle, was just like the Centennial Trail.

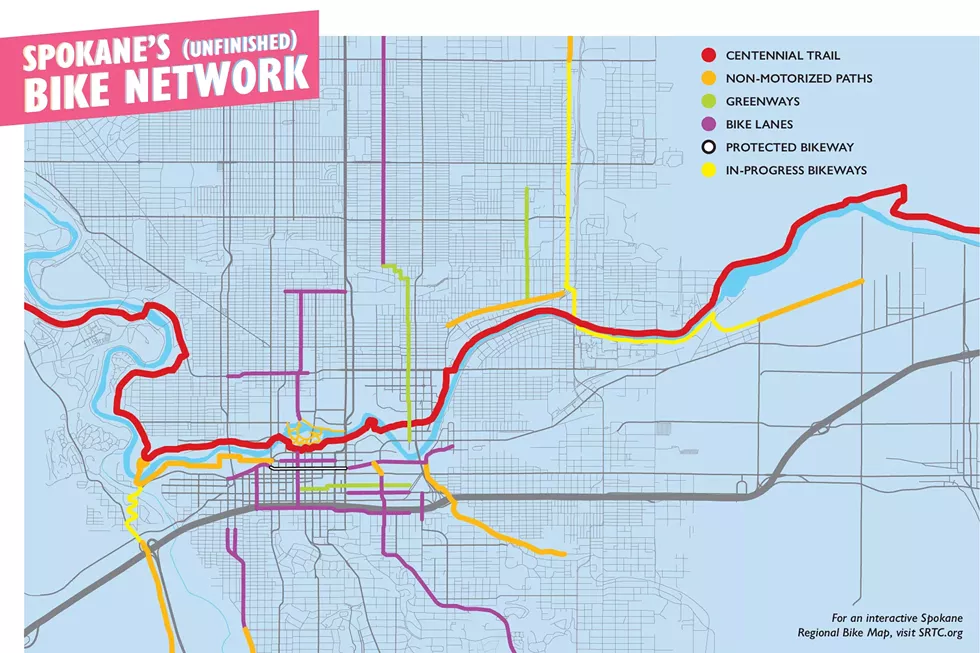

Spokane, I realized, has a bike highway. Our very own doorfietsroute. Like Nijmegen's path, our route converges on the city center, offering the possibility of drawing commuters from as far as Coeur d'Alene or Nine Mile.

But there are major gaps, dashing the idea of "keep going." While there are magnificent unencumbered stretches, there are also major points of danger and confusion. Riding along Upriver Drive in the Minnehaha neighborhood is fine if you think a thick line of white paint will protect you. But good luck getting across Argonne Road in Millwood, or through the bewildering route of Post Falls.

But van Duren, who traveled to the University of Oregon earlier this month with people from the Dutch Cycling Embassy and Urban Cycling Institute to lead a series of "ThinkBike" workshops, says the Centennial Trail is the foundation of our future city of bicycles.

"It can function as your backbone," he said over Zoom from his hotel in Bend. "The problem with the Centennial Trail is it doesn't really connect to anything. You're missing the last few 100 feet. And certainly, if you're scared as hell to go three blocks downtown in Spokane, then it's not being used functionally, just leisurely. If you want to develop your network, stop working away from the Centennial Trail's great connection."

As we spoke, my mind flashed back to a trip I took to Taipei, Taiwan, in 2016. I rented a bike near my Airbnb and rode along the Tamsui River Cycle Path.

I used the route as a tourist — leisurely — riding to the waterfront where I felt like I was in an Oregon coastal town, snacking on stinky tofu instead of saltwater taffy. But it was clear this path was primarily for commuters, the working people in the island's capital city. Every mile or so, a cafe would appear on the trail, with grab-and-go dan bing egg crepes and hot soy milk for those "functional" riders.

Once I was off the trail, however, it was like riding in Spokane — if Spokane had 2.6 million people and about a quarter of the commuting population traveled by moped. It was intense, but I knew then as I do now what van Duren was saying. A bike highway is great, but it needs to be complete, let people ride with little or no places to be hung up or confused, and connect to a network of safe bikeways.

That's what the Centennial Trail needs. That and more cafes for the morning commute.

SEPARATED BIKEWAYS

James Thoem works spreading the good word of Copenhagen, Denmark. That word is: "Copenhagenize."

In fact, that's the name of Thoem's company. As I sat in the Copenhagenize Design Co.'s offices, just a few minutes from the twisting and flying Bicycle Snake Bridge, I knew he was right. When it comes to bicycles, any city in the world can do like the Danish capital.

I spent nine days in Copenhagen riding everywhere I went, including to do laundry at a diner in the Østerbro neighborhood. What I experienced can be replicated in any city with a road. Just add a bike lane between the sidewalk and street that's not on the same level as either. It's a little lower than the sidewalk, and a little higher than the road.

Though the exact design varies from city to city, these "separated" bikeways are beginning to take over the world. Bogotá, Colombia; Ljubljana, Slovenia; Xiamen, China; Vancouver, British Columbia; and Lagos, Nigeria, have them. And, wait for it, Spokane is building one as you read this, downtown on Riverside Avenue.

"This is the first," says Colin Quinn-Hurst, a planner with the city who spends part of his time focusing on bike infrastructure, as we stand next to the partially completed bikeway. "It took awhile to design. It was new for us. But we're excited to see how people use it."

It's coming together well, with green lanes to notify motorists of people on bikes, and parking between much of the bike and car lanes, providing not just a steel wall of protection, but a known method of getting people to drive more carefully.

As Quinn-Hurst notes, it may be new to Spokane, but 130 American cities have similar bikeways. They're building them not out of blind bike love, but for safety.

A 2019 study looking at 13 years of data in 12 American cities showed that separated bike lanes actually make the streets safer for everyone — whether they're on bike, foot or driving.

Portland, one of the cities, shows just how powerful safe bikeways can be when it comes to saving lives. Between 1990 and 2010, the proportion of overall trips taken in separated lanes increased from 1.2 percent to 6 percent. During the same period, the road fatality rate dropped by 75 percent.

"It's better for everyone," Quinn-Hurst says.

But, count it, it's just one protected bike lane in all of the city. We need more.

As Copenhagen's network of protected bikeways has grown, it's used more and more. In 1994, when the city really began investing in its network, about 30 percent of people rode their bike to work or school. Now, less than 30 years later, that rate is 62 percent.

It's a wonder to witness. One June morning, on Thoem's suggestion, I sat on the east end of Queen Louise's Bridge watching morning commuters stream by, just a fraction of the 48,000 bikes that cross the bridge every day. Every 45 seconds the signal on the bridge's east end would turn green, and the river of people on bikes would flow, only to be dammed by a red light, packing riders densely on the bikeway, waiting for the next 45-second cycle.

It's an unambiguous example that bikes are the most efficient way for a city to move. A standard bike lane can move 6,000 people every hour, according to the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). In a car lane, that number drops to 1,300 people an hour.

A CITY NETWORK

As I stared at the river of Danish commuters, my American eyes disbelieved what they saw. Yet there was something they found familiar. Cars. There are still many cars in Copenhagen, and every street still accommodates them. They simply now share the space they had unilateral access to for decades.

Spokane, whose downtown streets have been described as wide enough to "shoot a cannon down," has space to share.

Rhonda Kae Young, a civil engineering professor at Gonzaga University who sits on the city's Bicycle Advisory Board, has already shown Spokane how that can be done by helping bring the Cincinnati Greenway to the Logan neighborhood. Cincinnati parallels the car-busy Hamilton Street along leafy neighborhood roads. Major crossings, such as on North Foothills Drive, are eased with a pedestrian signal triggered by the touch of a button.

Everyone wins. Bikes stay off the car street, and cars generally stay off the greenway. When the residents drive on the street, it's at a slow, safe speed. To borrow a Dutch term, the traffic has been "disentangled."

"Too much of the conversation has been framed around which mode wins. If there's a winner, there must be a loser," says Young. "It's not about forcing anyone out of their car. In a system that works well, if someone rides a bike it helps you" as a motorist, pedestrian, transit rider or anyone else.

As I saw in Denmark and even in Amsterdam, cars go everywhere. So do trains and buses and pedestrians. When I was in northern Europe, I struggled with the American idea of "freedom" and how at odds it is with our transportation system. We're generally given one choice on how we're going to get anywhere: the car. Liberty literally means the power, right and opportunity to choose. I guess the liberty-loving Scandinavians and Dutch have us beat.

Still, choice is something we should demand. And to make bicycling a viable option, a robust and connected bike network is necessary. As it is, we have a lot of bikeway fragments that don't link together.

"When I think about the big picture things, it's the connectivity," Young says. "We're really good at having these high-quality destination trails, but it's the pieces. We need connectivity between jobs and housing. It's such a low-cost way to handle transportation."

Which is where Riverside's new bikeway comes in.

When complete in the spring, Riverside will act as the "missing link" for the central city's numerous trails, says Quinn-Hurst, the city planner. With this one refurbished road, people on bikes will more easily ride between the Centennial, Ben Burr and South Gorge trails. Quinn-Hurst is also working on a connection from the Gorge trail — which loops around Peaceful Valley, Kendall Yards and Riverfront Park — to the Fish Lake Trail and Cheney.

A humble beginning of what could be a vast urban bike network, and it was an add-on to a needed, already-on-the-books road construction project. What's more, people in cars won't see a change in their commute times. Not until the network grows and more people are riding and not driving. But to get there, the network must grow, something Young, Quinn-Hurst and others are working on.

The city has funded projects in the works to build greenways on Pacific Avenue through downtown from Browne Street to Sherman Avenue, and on Cook Street in northeast Spokane. Work is underway building a biking and walking path on Illinois Avenue. And, after a lengthy application and interview process, the city just joined NACTO, a federally recognized coalition of cities that provides support and research about how to solve the complex transportation issues of the 21st century.

SLOW STREETS

I had emerged from Utrecht's Wilhelmina Park and was heading southeast toward the Dutch city's university on a treed street lined with homes and parked cars. I passed a sign that read, Fietstraat. Auto te gast. Bicycle street. Cars are guests.

Ahead of me three boys, maybe 10 or 11, rode side by side, acting like boys do. Oblivious to the world around them. A car slowly drove behind them, not too close. Three or four blocks passed. More people on bikes and a handful of cars came from the other direction. Seeing their chance to pass, the motorist gained a little speed and passed the boys at a safe distance, still going a comfortable pace of 30 kilometers per hour — 18 mph.

I couldn't believe it. The boys showed no sense of impending danger or fear they were in the way. The motorist wasn't aggressive.

Still, most Americans probably share my initial thought: This is not safe. A fear not misplaced. Every single day in America, 22 children are struck by cars, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Those kids, a number equivalent to a kindergarten class, are lucky. They survive. In 2019, 221 children who were either walking or riding a bike were killed by drivers in the U.S.

What makes this senseless loss even harder to accept is the fact that pedestrians once had free rein to the street.

"Around 1910 or so, you would've seen people walking all over the street. You would see streets being used like public spaces," says Peter Norton, a transportation historian at the University of Virginia, in the new PBS documentary, The Street Project.

In his book, Fighting Traffic, Norton describes the scourge on American streets 100 years ago, when cars appeared and motorists blazed through neighborhoods. In 1921 alone, 1,054 kids were struck and killed in New York City.

Cities erected monuments memorializing the dead children and passed laws to control speeding drivers. The auto industry and automobile clubs pushed back, leading systematic campaigns to stigmatize how people had always used the street. They even coined the new term "jaywalker," which basically said only country bumpkins — "jays" — didn't know how to cross a street.

It worked. In the end, the car won and now most of us simply accept that our streets are for the exclusive use of autos.

And overall road fatalities continue, a sad tally that reached 46,000 dead in the U.S. last year. Data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and National Safety Council shows that Washington state traffic fatalities continue to climb, with an increase of 31 percent this year over last.

Calling all of this murder is a bridge too far for most Americans, but it was such directness in language that led to change in the Netherlands 50 years ago.

Through the 1950s and '60s, Dutch city planners followed the American mode of knocking down neighborhoods in favor of highways. But when the child of a journalist named Vic Langenhoff at the newspaper De Tijd was struck and killed by a motorist, Langenhoff began writing a series of columns.

The first was headlined, "Stop de Kindermoord." Stop the murder of children.

His writing galvanized the city. Parents, children, activists and politicians banded together. In 1970, the Netherlands experienced 245 traffic deaths per million people, a number equivalent to the current U.S. rate of 257 per million. Now, the country sees 34 deaths per million — 70 percent lower than the fatality rate here in America.

What can be done? Look to Copenhagen, which like Spokane is a city of parks.

For instance, there's the Trafiklegespladen — the Traffic Playground. Here, children as young as two learn how to ride a bike in traffic. They're given whatever two-wheeled machine they can handle — pedal-less balance bikes all the way to standard models — and let loose. In a tiny model cityscape, complete with traffic signals, yield signs, bike lanes. To learn on their own. They end up getting it, simply through play.

It gives the people of Denmark mobility and independence early in life. In Odense, the nation's third-largest city, 5-year-olds ride their bikes to school. Parents who do drive their kids are warned that they'll be ticketed if they park in front of the school.

There, four out of five children bike or walk to school — a situation not unlike in the U.S. not that long ago. In 1970, half of American elementary and middle schoolers walked or biked. Now, only 11 percent of children walk or bike, according to the National Household Travel Survey.

It's a shame, too. As any Dutch or Danish citizen will say, the bike gives children a sense of freedom. And responsibility. And exercise.

We don't have that here, but we do have Spokane Summer Parkways, where once a year 4 miles of streets on the South Hill are closed to cars, allowing any kind of human-powered transportation.

Katherine Widing's been at the helm of the solstice event since 2010. A native of Australia, Widing has lived in Spokane for nearly 40 years and made a career out of writing bicycling guidebooks for Holland, France, Belgium and around Washington state.

So she knows good places for bikes when she sees them. This year, she saw it.

"This year, we had 3- to 4,000 people," she said of Summer Parkways, the largest number yet for the event. "The atmosphere was just amazing."

The idea is simple. Close the streets to autos, and let people come out and enjoy the shared, public space. People on bikes, roller skates, skateboards, walking.

"Our reward is seeing happy people," Widing says. "Seeing a little girl with butterfly wings and pink tutu riding a pink bike makes it all worth it."

But Widing wants more, and she has some ideas. Namely, ciclovías.

CICLOVÍAS

When a guy on a skateboard being pulled by his dog flew by El Ángel de la Independencia, I knew I was seeing something special.

It was a Sunday, and like every Sunday on Avenida Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City, this major road of the capital was closed to autos. It was a festival, a fair, a party, a massive picnic. It was ciclovía, a weekly event that regularly draws 50,000 people.

Spanish for "cycleway," ciclovías began in Bogotá in 1974, when the pollution-choked and traffic-jammed Colombian capital banned cars from some of its major roads in an effort to curb pollution and traffic. Two generations of Colombians have grown up with the event, and running it — closing streets, ensuring it's safe — is part of the city's official duties.

That's what Widing thinks should happen here.

"It takes a lot of work. It's a big event," she says, noting that she and six other volunteers have made Summer Parkways happen for more than a decade. "It doesn't have to be a big event. But the city has to be involved."

Widing sees a future where it becomes an official city event, like ciclovías are in dozens and dozens of other cities around the world. Because the biggest cost and headaches of Summer Parkways, she says, come with securing the proper permits and ensuring police are on hand to route auto traffic.

With the city running the show, the event could happen multiple times a year, and in different locations. Imagine a sunny Sunday riding around the Altamont Loop and down South Perry Street with the district's many restaurants and stores doing sidewalk business. Or on Garland Avenue. Around Corbin Park. North Market Street. Even Northwest Boulevard.

I experienced just such a rotating ciclovía in Los Angeles, where I spent the last year studying urban planning. First, we rode downtown, into Chinatown and around MacArthur Park. A few months later, we were in South LA, cycling on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and by the Memorial Coliseum. Then, this summer, we rode on Hollywood Boulevard.

Each time, I thought of Spokane's different neighborhoods and celebrated business districts. And I wondered, could Spokane do it?

"Yeah, definitely," said van Duren, the Nijmegen planner, when I asked if Spokane could be a place where bicycles are a major part of life. "Amsterdam wasn't always Amsterdam."

Spokane, van Duren said, has the advantage of being a medium-sized city that's relatively dense — thanks to our history of streetcar suburbs and booming before the advent of the car — that's relatively flat, and that still has local politics.

"If they want to act, they can be quite effective," he said of city officials. "Enjoy that. Use that and see what you can do. Because, yeah, it is definitely possible. But it's not an overnight thing. And you should not try to sell it as an overnight thing. It isn't. It just takes work." ♦