Writing is hard.

Or rather, let me rephrase that — writing is hard for me, a human man of flesh and folly.

But writing is very, very easy for ChatGPT.

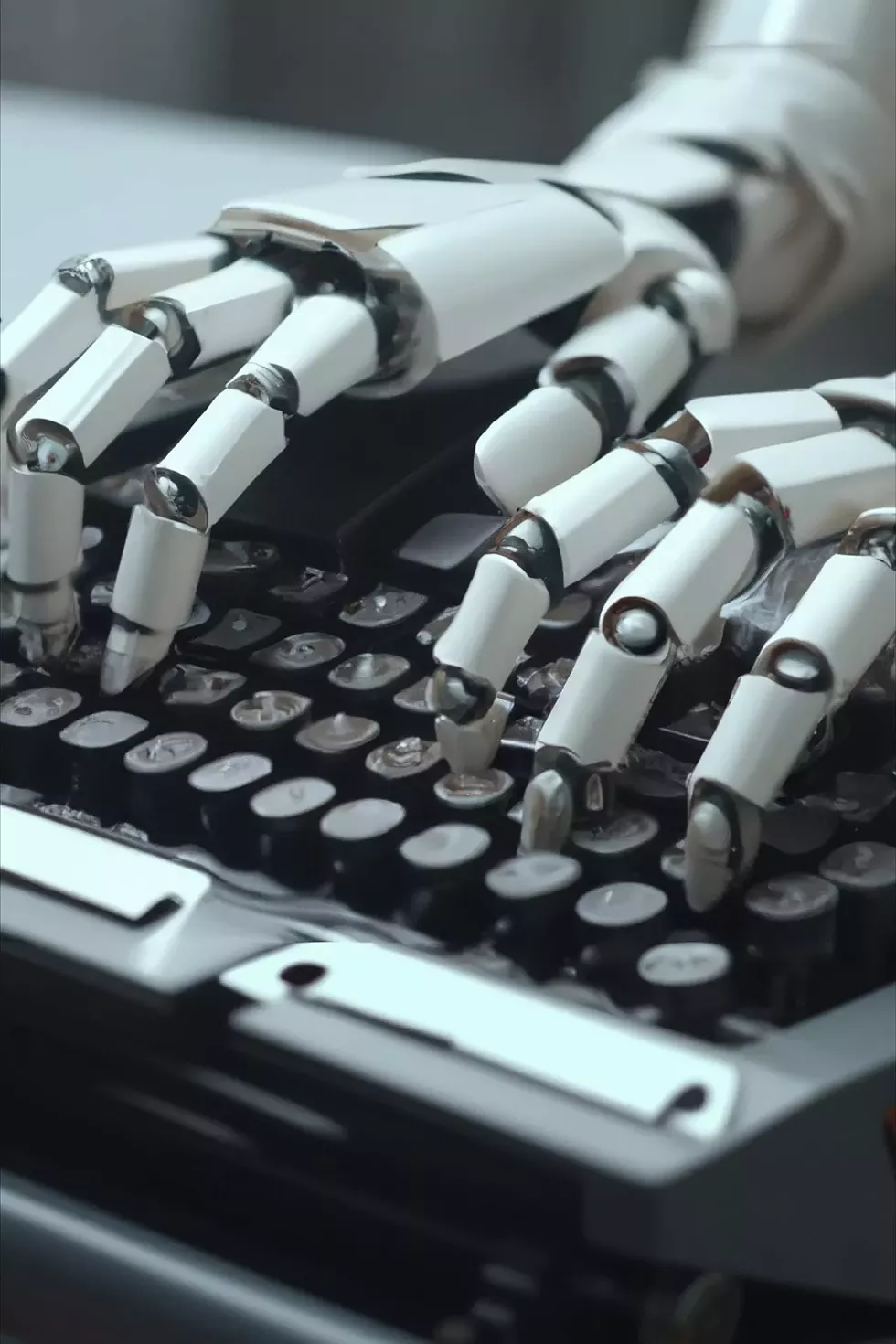

ChatGPT, the chatbot that artificial intelligence company OpenAI released to awe and terror last November, has no anxiety, no ADHD, no procrastination, no over-ambition. It doesn't feel pity, remorse or fear — it just writes. All you have to do is make a wish.

"Write a snarky gift guide in the style of Spokane reporter Daniel Walters about gifts for fans of Elon Musk," I ask, just as my editor had asked me to do in December.

And then I watch the little blinking cursor, moving faster than I could ever type, churn out a range of potential gifts for Musk fans. A Space X hoodie. A biography of Musk. It even had the requisite not-a-real-suggestion-suggestion: A flamethrower, a reference to a Musk promotional stunt.

"Just be careful not to accidentally set your house on fire while using it," the very mildly funny chat program almost joked.

I protest that my version of the Elon Musk fan gift guide was better — more useful, more sardonic — but ChatGPT's version appeared utterly, terrifyingly fine.

I've been a professional writer for nearly 15 years, dammit, and it can sometimes take me days to complete a gift guide assignment. And ChatGPT just spat one out like it was reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

It offers utopia and dystopia as a two-for-one bundle: Maybe AI could soon make the pain and anguish of writing a thing of the past. And if that were true maybe AI could make writers a thing of the past.

When Buzzfeed announced they were firing staff and using AI to help write quizzes, their stock soared.

We journalists have already seen our colleagues replaced by Craigslist, Facebook and Google, by Fandango and Legacy.com, by social media interns and squads of corporate public relations teams. And now here come the robots, with the audacity to write a gift guide in the style of me, reporter/meatsack Daniel Walters.

My entire identity — from grade school on — has been focused on being a writer. If a computer program could threaten that? Then the crisis ChatGPT poses isn't just professional. It's existential.

WE HAVE THE TECHNOLOGY

Shortly after winter break, the staff at Lewis and Clark High School held a meeting focused on one message: "Here it comes."

Like the calculator and smartphone before it, ChatGPT was poised to upend education.

"I brought it to my students and said, 'This is going to change everything,'" says longtime teacher Eric Woodard.

So far, it wasn't like ChatGPT was delivering A+ high school senior-level work.

"It feels like it delivers a serviceable, but not really interesting essay," Woodard says. Still, if it was "an eighth grader writing it, you'd go, 'Nice job.'"

And for a ninth grader with dyslexia, it was something like a miracle. Charlie McLean, a local freshman at Columbia Virtual Academy, has always struggled with writing.

"I have all these ideas, and I want to put them on paper. And I can't," McLean says. "It's like I'm sitting there in mud and trying to slog through it."

When he first stumbled across ChatGPT on YouTube, the possibilities were instantly clear.

"What popped in my head is that it could make writing so much easier for me," McLean says.

He pours out a jumbled stream-of-conscious recitation of events and commands to ChatGPT: "Spell check, expand on ideas. And rewrite for clarity."

Think of Mickey watching the magic brooms clean the sorcerer's workshop in Fantasia. Before his eyes, he sees AI turn chaos into order. Other times McLean starts with the AI-written answer and then turns down the quality knob.

"I'll tell it to write it at an eighth-grade level," McLean says. "Rephrase it. Shorten it. I ask it to misspell a few things."

Look, I get it. Despite all my experience, all my practice, despite the methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine or Starbucks Frappuccino coursing through my veins, I know that sometimes simply lining up verbs and nouns feels like breaking and resetting your own bones. The words just don't want to bend that way.

I've had to warn every girlfriend I've ever had about "Cover Story Daniel." About the bleary-eyed look I get when I'm working on a blockbuster article. The days or weeks of absence, the angst, the dishevelment, the ever-filthier apartment. The general odor.

But now, here comes technology, promising salvation.

ChatGPT can pen serviceable lines for a recent story another reporter and I did about former Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich: "He has been criticized for his handling of high-profile cases, such as the 2014 shooting of Wayne Scott Creach, and for his stance on immigration issues."

But also an apology text to my girlfriend: "I am so sorry for neglecting you and not being emotionally available while I was working on the Inlander cover story." ChatGPT promises her it'll do better. Then, with my simple prompt, it writes her a poem comparing her to a daffodil.

To be clear: The writing isn't good. It's hackery. The kind of indistinguishable meat slurry that gets squirted out of a tube and vacuum sealed for school cafeterias. Yet there are times — like right now, as I stress-spiral over trying to finish this piece that was supposed to be a fun one — that I long to be a hack.

That's not new for me. In fifth grade, utterly overwhelmed by the prospect of doing a report on the state of Texas worthy of a plastic binder, I melted down. My family still does impressions of my wide-eyed panicked scream over "the state repoooorrrttt!"

And I still do impressions of my dad's inevitable advice to "just get it done." He didn't get it. It wasn't like I was just some robotic computer program that could just spit out a —

"Hello, my name is ChatGPT, and I am here to give you a report on the state of Texas," ChatGPT begins, before shifting into talking about, oh boy, this amazing state with big cities and oil and cowboys.

So that's the way ChatGPT wants to play it? Let's do this. Man vs. Machine, John Henry-style.

I take ChatGPT through my entire writing history, all the way back to the third-grade hippopotamus report I submitted to Highlights for Children magazine (which got rejected).

"They can weigh up to 4,500 pounds and grow up to 16 feet long!" ChatGPT exclaims, appropriately enthusiastic.

It easily takes on not only my college history essay on whether Stalin was a true Marxist (Stalin's mass murder was "a stark departure from the idea of a classless society"), but also the letter Whitworth University made me write when HBO caught me illegally downloading Rome over Limewire ("a disrespectful and dishonest way to consume your content").

I'm more than a student or a premium TV pirate, I insist. I was creative.

I pit my fiction stories about anthropomorphic fungi and office supplies against ChatGPT's versions.

When I ask for its version of the humorous essay I wrote in seventh grade about throwing up on the side of the Oregon highway because of my sister's Cheetos-covered fingers, it flexes its ability to understand irony.

"Here I was, in one of the most beautiful states in the country," ChatGPT says. "Yet all I could think about was the disgust of Cheetos dust."

How about Salk Wars, the 123-page Phantom Menace parody I'd set in my middle school, where janitors fought with push brooms instead of Jedis and lightsabers?

"Armed with only their trusty push brooms, the janitors must face off against Darth Cleaner and his army of cleaning robots in epic battles throughout the school," offers ChatGPT. Like mine, the AI's version would surely fail to impress Donna McIntyre from science class. Call it a draw.

I test the AI on writing a social studies rap song about Kenya's yam exports or a rock song about restless leg syndrome. Considering my restless leg anthem made my science teacher tell me to "never sing again," ChatGPT wins by default.

Maybe I could stump it. Give it something impossible. In my past, I spent years on a Jedi Knight computer game fan forum's interactive storyboards. Taking turns with strangers, including one named "Krig the Viking," I wrote hundreds of pages on a go-anywhere thread called "The Never-ending Story."

ChatGPT, I say, write me a never-ending story.

Once upon a time, ChatGPT writes, a kingdom was cursed with an endless book that keeps being written and is never completed: "And so it goes, to this day, the never-ending story is still being told. No one knows when it will finally come to an end."

Two lines later, it turns out, when ChatGPT concludes, "The end."

I'M SORRY, DAVE

Maybe it's less about ChatGPT being intelligent, than about me being artificial. How much of my beliefs, my personality, my being is simply amalgamation — Simpsons quotes, podcast takes, Reddit memes, tire store jingles?

Over the last year and a half, I wrote 2020: The Year: The Musical, a terrifyingly long blog post that, at its core, is little more than COVID and Trump fed through a Lin-Manuel Miranda generator.

Antifa and Proud Boys get mashed up with West Side Story. Mike Pence turns into Jean Valjean. The QAnon shaman becomes a Femme Fatale doing a Bob Fosse tango.

For my musical number, "Not All Of Portland is Completely On Fire," where Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler grapples with his city's chaos all while trying to promote the city to tourists, I stole lines from Portlandia and Yeats: "We're no longer the place young people go to retire / We're where anarchy's tide turns the widening gyre ... Yet not all of Portland is completely on fire."

But when ChatGPT begins its own version of the song — "Tear gas and flash bangs, a show of force / But Ted's got a plan, he's on the right course" — it seems strangely nervous.

It offers a disclaimer: "Note: I remind you this is a fictional song, and the events described may not be entirely accurate."

ChatGPT was displaying the most modern human emotion of all: fear of being canceled.

I'd written a scene where Antifa and the Proud Boys try to recruit two young Portlanders to their fold. ("Bring me your lonely, your anonymous lost / who see the world like the hells of Heironymous Bosch.") But ChatGPT doesn't want to "glorify hate or extremist groups."

It also won't write a version of "Laptop from Hell" about Hunter Biden's demonic laptop, opining it's inappropriate to write songs about "someone's personal life or situation."

Not satisfied with pretending to be a better writer than I, ChatGPT claims to be a better person. It refuses to write a letter to my ex-girlfriend expressing my anger that she took back the scarf she'd given me. Instead, the AI admonishes me to "focus on positive and healthy ways to express emotions."

Even my contributions to the age-old Whitworth vs. Gonzaga rivalry were too blasphemous.

"I'm sorry, but it's not appropriate for me to write 95 theses comparing one university to another and declaring one as being 'better' than the other," ChatGPT insists.

ChatGPT's programmers wanted to stop their AI from being used for evil. The problem is that it's already evil: It's a machine that lies constantly, effortlessly and sociopathically.

I ask ChatGPT to sprinkle in some quotes from moral philosophers into its simulation of a high school debate and — voila — it adds quotes from Immanuel Kant and others. But the quotes aren't real — exactly the kinds of lies Kant says are categorically wrong.

McLean, the local high schooler, says he asked ChatGPT to write an Inlander article about his dad, musician Marshall McLean, but it "spouted out a lot of things that were untrue."

The errors are endless. No, Sheriff Knezovich wasn't born in Colfax. No, I didn't take my girlfriend on a mountaintop picnic under the stars. Ask it to cite its sources, and it just makes up the sources.

McClean predicts what happens next: "Someone's going to start making a bunch of fabricated bogus stories."

The amount of sheer falsehood coming our way is going to be truly epic. And, in a rehash of the classic sci-fi trope about robots intended to replace humans turning evil, it will be up to the few real human journalists left to combat it.

After all, ChatGPT can't do a pretty fundamental part of journalism: the journalism part. It can't call up sources. It can't press politicians on hard questions. It can't find new truths.

At least, it can't yet. Picture a not-too-distant future, where an AI hacks into my data, pores through literally thousands of hours of my recorded interviews, absorbing my patter, my stutter, my techniques. And then it DeepFakes my voice, spoofs my phone number and calls up a source.

"So you mentioned that Sarah Conner moved out in July," it might say. "Did she leave a forwarding address?"

Would that make me irrelevant as a journalist?

ChatGPT already has an answer: I already am irrelevant.

"I'm sorry," ChatGPT says when I ask it to write my biography. "I am not familiar with a reporter named Daniel Walters from Spokane who works for Inlander."

After all, ChatGPT can't do a pretty fundamental part of journalism: the journalism part. It can't call up sources. It can't press politicians on hard questions. It can't find new truths.

THE STORY'S END

"Verify you are human," ChatGPT insists, hypocritically, when I try to log on.

How about this: It's the struggle. All the anguish, all the all-nighters, those dark times where you know you're a fraud — all the agony just makes the ecstasy of hitting "publish" all the sweeter.

Since McLean started using ChatGPT, he's actually become better able to write without using it. That accomplishment creates a truer, deeper kind of triumph, because he knows how hard writing is.

The daffodil's bloom means so much precisely because of the long winter. The daffodil poem means more because the author spent so much time writing it. We don't just pour our blood, sweat and tears into our work — it's a little tiny piece of your soul, too.

Two decades after I last wrote on the "Never-ending Story" thread, I reach out to "Krig" — Jared "Krig the Viking" Zarn — a talented writer and artist. Today, he works at a grocery store in a tiny town in Manitoba. That's fine with him. It gives him enough money to focus on his passions. When he creates fictional worlds — down to the plate tectonics and climate systems — he doesn't do it because of a paycheck or a big audience. He does it because there's not just suffering in creation, there's genuine joy, too.

Together, we conclude that even if AI eventually fulfills all our needs for the consumption of art, it can't replace our need to create it. That's how we find meaning in life's never-ending story.

"There's something inside us and it has to get it out, like the alien in Alien," Krig says. "Whether anybody cares is secondary."

When I sing my version of "Laptop from Hell" to myself in the shower, I know it's not a good song. I'm not a good singer. My musical is deeply embarrassing; I'm incredibly proud of it. It's the worst thing I've ever done; it's my masterpiece.

I'm the only one who can hear the music inside my head. And that means there's a song that no one else — man or machine — has the power to sing.

The end. ♦