Every serious pinball player remembers their first machine. Ask any of them, and they'll tell you about it.

Maybe it was glittering in the back corner of the neighborhood arcade, or pinging and clanging over the din of the local tavern. Or, if you were lucky, you had a friend whose parents bought one for their den, and you could play it all afternoon without ever having to put a single quarter into it.

I had my own childhood pinball machine, and its silver spheres have been bouncing off the bumpers of my brain for years. It sat in the game room of the pizza parlor that my grandmother owned, and I sometimes had it to myself in the hours before the restaurant opened. I remember marveling at the artwork on the machine's back panel — a femme android floated in the void of space, striking a regal, balletic pose as menacing cyborg hands with pinball flippers for fingers enveloped her, shooting electricity into the cosmos. On the side of the machine's cabinet was a red-and-yellow egg-shaped robot, its spindly mechanical arms frozen in a comical shrug.

There was a drawer in the restaurant's back office with a Styrofoam cup that magically replenished itself with coins. I'd plug that machine with a fistful of quarters, but I don't think I ever got more than a few seconds on each credit, furiously smashing the buttons as the balls sailed right past my flippers and into oblivion. But I was nonetheless hypnotized by this contraption — its flashing rainbow of colors, its intergalactic sound effects, its weird cast of characters. I've been trying to remember more details about this particular pinball machine for years, but it has been shoved into a corner of my memory, its title covered by a layer of dust and cobwebs.

Pinball seemed to me like a grown-up game, and not just because you had to stand on your tiptoes to play it. When the adolescent boy in the 1988 comedy Big transformed into adult Tom Hanks, I was less impressed by his beautiful Manhattan loft than the pinball machine he had in there. Surely that was the sign that you were a capital-A Adult.

It's fuzzy, neon-tinged memories like this that have no doubt inspired pinball's resurgence in recent years, as the generations who grew up during the arcade boom (and its eventual bust) or witnessed the game's unlikely 1990s renaissance are rediscovering its unusual charms. It's hardly a world-shifting movement, but consider that there are more active pinball manufacturers in 2020 than there were in 2010.

Of course, lots of old-school video games have been recreated for contemporary gamers: Look no further than the popular Nintendo Classic toys, preloaded with a selection of 8-bit titles from the '90s, or the online emulators that allow you to download retro games to your computer in seconds. But pinball is not so easily replicated, and unless you know somebody with their own machine, you have to seek it out to play it.

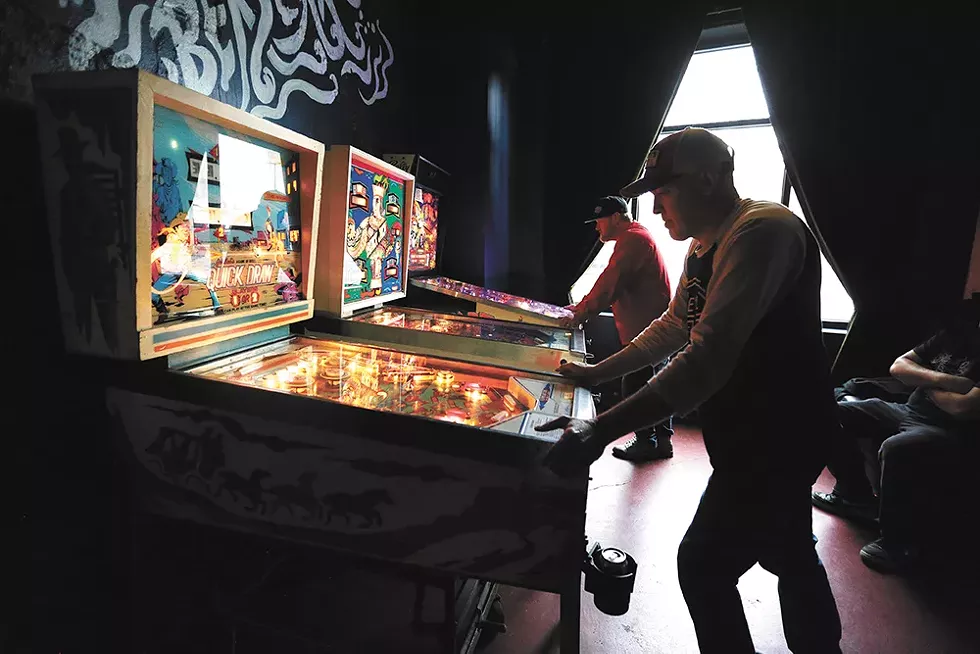

That's why I set off on a freezing Wednesday afternoon to meet up with pinball fanatic Bryce Rich at the downtown bar Berserk. The place has eight operating pinball cabinets, ranging from a 1975 Western shootout called Fast Draw to the 1996 billiards game Breakshot. Rich puts some credits on an early '90s machine titled Game Show, in which you score points and collect "fabulous prizes" — a new car, a Caribbean vacation, a color TV.

I pay careful attention to his approach. He gently rocks the machine at just the right moments, jockeying the ball between the two flippers as he carefully considers his next move. I've always thought of pinball as a game of breakneck speed, of distracting lights and noises. Yet he's managed to slow it down into an activity of almost zen-like concentration.

In between turns, I ask him why pinball appeals to him.

"It's the entire package. The way they look, the way they sound," Rich tells me. "Being able to rally with your friends — drink beer and play pinball. You can't play it on your Xbox, you can't play it on your phone. There's no cheat codes. And it's super competitive."

After downing my first Miller High Life, I figure I can use Rich's encyclopedic pinball knowledge to my advantage, and I start quizzing him with vague details of that old pinball machine I loved when I was a second grader: It was in space, I think? And there was this robot on the side... He picks up his phone, types in a couple words, and holds it out to me. There it is on the screen: Pin-Bot, a 1986 machine that was so popular it was turned into a Nintendo game. It's also the same machine that Tom Hanks owns in Big.

"I get asked that sort of thing all the time," he says as I scroll through the pictures.

CRAZY FLIPPER FINGERS

Like any arcade game, pinball takes some time to learn and master. And like arcade games, each pinball machine is different from the next, not just in design and theme but in its construction and prescribed set of rules.

But the basic strategy of every modern pinball machine is the same: Those silver balls come flying at you on a downward-slanted playfield, and you use the flippers to prevent them from falling into the pocket at the base of the machine known as the drain. Rack up points by completing certain objectives, which will set off a chain reaction of even more objectives. A really good game of pinball is a symphony of on-the-spot hand-eye coordination and calculated strategy.

"The thing that people don't understand about pinball machines, even the old ones, is that there's a deep rule set," says Tyler Arnold, a local pinball collector who owns the arcade Jedi Alliance, off Napa Street in the Chief Garry Park neighborhood. "It's not just 'whack the ball around and see what happens.'"

In pinball, gravity is both your friend and your enemy. You can nudge the machine to make the ball obey, but too much jostling and the machine immediately ends your turn (that's a "tilt" in pinball parlance). The amount of force you apply to the flippers determines where the ball goes, and at what velocity.

"I became a teenager when video game arcades started popping up everywhere," recalls James Hunt, a co-owner of Berserk. "But before that, I was playing pinball at burger joints with my dad. ... It's the same thing as video games — you work on developing these shots and techniques — but I think you can be a little more nuanced with pinball."

And then there's the art. You can trace the evolution of pinball through its visual trends — the fairground aesthetics of the 1940s, the art deco-like simplicity of the '50s, the spaceships and astronauts that dominate machines in the wake of Star Wars and the more cluttered, movie poster-style layouts of the '90s.

Within pinball circles, specific artists and designers like Steve Ritchie, John Youssi, Gordon Morison and the wonderfully named Python Anghelo are revered.

Arnold likens the very design of the pinball machine to a display case, and to Jedi Alliance as a museum. "But people are allowed to come in and play with the artifacts," he says.

THERE HAS TO BE A TWIST

Pinball's historical trajectory is about as winding and serpentine as one of the ramps inside your standard machine.

Its origins are usually traced to tabletop games that were popular in pre-Revolutionary France, but the true progenitors of the contemporary pinball machine — simplistic games at bar counters that allowed players to navigate balls around wooden or metal pegs — first thrived in America during the Great Depression as a form of inexpensive amusement. The game became more elaborate as its popularity increased, with pinball designers inventing features (plungers that send the ball onto the playfield, obstacles accompanied by sound effects and flashing lights, mechanized flippers) that remain standard. Multiplayer capabilities soon followed, as did digital scorekeepers and more intricate, interactive doodads.

According to the 2009 documentary Special When Lit, pinball companies raked in more money between 1955 and 1970 than the entire movie industry. The Who's 1969 rock opera Tommy — it's about a deaf and blind boy whose inexplicable pinball wizardry inspires religious hysteria — no doubt spurred its popularity. Director Ken Russell's gloriously baroque 1975 film adaptation of the Who album features Elton John performing the hit song "Pinball Wizard" in a knit beanie and towering platform shoes, which ensured that both the movie and Sir Elton became two of the first pop-culture properties to have their images licensed for pinball machines.

While these innovations were happening, one place missed out on all of it: the Big Apple.

In the late 1930s, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, concerned that the proliferation of coin-operated gaming would merely encourage gambling, outlawed pinball within city limits. Machines were confiscated from businesses and either smashed with sledgehammers or dumped into the Hudson River. Other major cities, including Los Angeles and Chicago (where most of the country's pinball machines were produced), followed La Guardia's lead, although the severity of those laws varied from place to place and tended to be loosely enforced. New York remained steadfast, however: Like booze during Prohibition, pinball was relegated to back rooms and secret compartments, and rumor has it that the mob cornered New York's contraband pinball market.

The ban remained in place until 1976, when journalist and pinball aficionado Roger Sharpe was brought before the New York City Council to prove that pinball was a game of skill over luck, and therefore not a form of illegal gambling. As six glowering councilmen looked on, Sharpe called out a complicated trick shot, Babe Ruth-style, before effortlessly nailing it, and it was a power move that convinced the local government to overturn La Guardia's antiquated edict.

The popularity of arcades would dwindle in the aftermath of the 1980s video game crash, and so, too, did interest in pinball. According to Adam Ruben's book Pinball Wizards, the company Williams Electronic Games produced 50,000 pinball machines in 1980. Three years later, only 2,300 left their factory. The demand simply wasn't there.

Production picked up steam again in the '90s when a pinball machine inspired by the 1991 film The Addams Family became an unexpected smash, and it's still the most commercially successful machine ever made. That unexpected uptick encouraged companies to increase production volume, which inevitably led to oversaturation. Coupled with the fact that pinball machines aren't exactly a breeze to maintain, and the market slumped yet again.

"Pinball had been in a precarious position to begin with," Ruben writes. "The abundance of pinball machines outran the efforts of the technicians, and machines fell into disrepair. Disrepair meant less interest from players, which meant fewer locations sinking their cash into pinball."

By the year 2000, most of the former titans of the pinball industry — Bally, Gottlieb, Capcom, Midway, Sega — were no longer producing machines.

THE DIGIT COUNTERS FALL

But like a compulsive player feeding a machine with quarters, pinball hasn't met a "game over" it couldn't brush off. It has repeatedly fallen out of fashion, only to be rediscovered and brought back from almost certain death by the next generation down the line.

"It went from treasure to trash and back to treasure," Arnold says. "People grow up with things, they have this nostalgia for it when they're in their 20s and 30s, and then when they start getting to the prime of their life, they buy it back."

Jedi Alliance houses the city's largest public pinball collection, with 35 or so working pins at any given time. Arnold considers himself a collector first, and every corner of his nerdly mecca is filled with vintage arcade cabinets, Star Wars memorabilia, comic books, action figures and, of course, pinball machines.

He bought his first pinball machine when he was 17 for $100 — it was at a used car lot, and it didn't work. But his collection started in earnest around 2003, a period when pinball was passe, and he got his hands on some older machines for a pittance.

"After we had a couple machines, we got a couple more," he says. "Then it became another, then another one, and another one, and so on."

The collector's market has gotten much more competitive in the 17 years since, Arnold says, and prices for in-demand machines (even mass-produced titles like the Addams Family) are higher: His most recent acquisition is a 1992 Creature from the Black Lagoon game, which ran around $6,000.

The handful of companies producing new pinball machines are selective in their output, and it's a busy year when a dozen unique titles hit the market. Most new pinball games are linked to recognizable properties: Stern, the country's preeminent pinball manufacturer (for years it was the only manufacturer), recently released Stranger Things and Deadpool machines, alongside reproductions of popular retro games like Black Knight and Star Wars. Thus far, the only new pinball title announced for 2020 is a hotly anticipated Rick & Morty game from the boutique retailer Spooky Pinball, while other independent manufacturers like Chicago Gaming Co. and Jersey Jack have made names for themselves.

Most of these new machines are produced in batches of 2,000 or fewer: That seems like nothing compared to the record-breaking 20,000 units of The Addams Family that exist, but it's also overshadowed by the once-typical production orders of common titles like 1985's Comet (8,100 units) and 1990's FunHouse (10,750 units). That's because most of these machines are going straight into the hands of collectors, and it's why most new titles are produced in multiple editions, which vary in special features and increase in price relative to their scarcity. (Consider: A standard copy of Stern's 2018 Beatles game starts around $6,000, and its special editions go up in price from there.)

There's another aspect to collecting that a lot of novices don't take into consideration: Machines can break in any number of ways, and it takes time and know-how to contend with the couple thousand feet of wire snaking around inside one.

Rich, who has been rehabbing arcade cabinets and pinball machines for a decade now, taught himself basic electrical skills so that he could repair his machines, watching YouTube tutorials and talking to other pinball fanatics in online forums. He says he usually acquires new machines through a network of collectors who keep each other informed: Someone texts him about a pinball machine that's languishing in a relative's basement, or about a friend of a friend who's looking to unload several non-working machines. Sometimes he sells them, or trades them for another machine. Sometimes he keeps them, or leases them out to businesses.

"Once you have a pinball machine in your house and enjoy having your friends come over and rally on it, you're always going to want one," Rich says. "And one's never really enough."

BUZZERS & BELLS

I had always thought of pinball as a solo activity, a barroom time-passer for when you're waiting for your friends to show up. But it's best enjoyed as a group activity, as a party game. That's reflected in the increasing interest of pinball leagues, which continue to pop up around the country: The International Flipper Pinball Association (yes, that is a real organization) lists about 75 currently active leagues on its website, and a couple hundred are set to start within the year.

Spokane's only pinball league, which meets at Berserk and is known as the Pinheads, begins its next season Feb. 3. During each week of its 10-week run, a pinball machine somewhere in town is chosen, and league members are encouraged to rack up points on that machine and submit their high scores. It's $35 to join each season, and members not only receive a commemorative T-shirt but can participate in bracketed tournaments that happen throughout the season. The last few seasons have attracted 30 to 40 players, says Berserk co-owner Beth McRae, and about half of them tend to participate in the various tournaments.

Marcus Schmick, who owns the lower South Hill bar the Park Inn, is a member of the Berserk league and won their first-ever tournament.

"It's just another level of competition," he says. "Everybody's playing, everybody's putting up a score. And just the cocky nature of being able to talk trash. There's not too many pinball players who don't talk trash to each other. It's like any other kind of competitive event."

Kaiti Black, co-owner of Spaceman Coffee, became obsessed with pinball as a Berserk regular, and she joined the league last year thinking it was a solitary hobby.

"It evolved from this thing I went out and did on my own into a 'hey, we're all here, let's play together' kind of thing," she says.

It's no secret that the pinball industry has skewed toward men, something that the manufacturers themselves were vocal about. (You can see their one-track minds reflected in the buxom, scantily clad women in so many vintage designs.) Black is one of only two or three women who have regularly played in the league, and while she acknowledges that the game is something of an "anachronism," the genuine rapport amongst her fellow players is not.

"That's the cool part of the community and the culture behind it," she says. "We're all here to play a f—-ing game, but we're all helping each other and we're all having fun."

I'VE PLAYED THE SILVER BALL

The Moezy Inn Tavern has been in owner Jason Huston's family since 1999, and it has almost always had a working pinball machine in it. Huston's late father was an ace pinball player, and in the early '80s he won a pinball competition at Critter McCoons, a restaurant that later became the now-shuttered Five Mile Heights Pizza Parlor. The grand prize of that competition: A pinball cabinet of his very own, which eventually took up residency in the basement of their house.

Berserk

125 S. Stevens

Coeur d'Alene Taphouse

210 Sherman, Coeur d'Alene

Coins Arcade

334 N. First, Ste. 206, Sandpoint

El Patio Bar & Grill

6902 W. Seltice, Post Falls

Gamers Arcade Bar

321 W. Sprague

Garageland

230 W. Riverside

Hi Neighbor Tavern

2201 N. Monroe

Jedi Alliance

2024 E. Boone

Lilac Lanes

1112 E. Magnesium

Market Street Pizza

2721 N. Market

Moezy Inn

2723 N. Monroe

The Northern Rail

5209 N. Market

Pacific Pizza

2001 W. Pacific

The Park Inn

103 W. Ninth

PJ's Bar & Grill

1717 N. Monroe

"We'd go down there and see him put up the high score, and then we'd spend hours on the machine," Huston says.

That machine, a 1978 Gottlieb game called Dragon, is now sitting in the corner of the Moezy Inn. Huston feels underneath the machine and flicks the power switch. The game comes to life, illuminating the back glass illustration of a warrior woman astride a reptilian creature, a lick of flame dancing on its protruding tongue. It's more of a sentimental keepsake than a game for customers to play, Huston's electronic memorial to the man who got him into pinball in the first place.

The back room at Jedi Alliance, meanwhile, holds about a dozen of Tyler Arnold's pinball machines, but one of them stands out above the rest. The 1996 GoldenEye cabinet has a commemorative plaque above it in honor of Arnold's late father, a massive James Bond fan.

"When I buy a machine, I don't think to myself, 'Is it going to bring in more money?'" Arnold says. "The side effect of my collection is that it also makes other people happy, which is pretty awesome."

It's a Sunday evening, and the doors to Jedi Alliance have just been unlocked. Customers have been milling outside for the last 15 minutes, and so Arnold heads back to the front counter. I turn my attention back to his collection, and that's when I see it — Pin-Bot, that machine from my youth, its lights twinkling at me like faraway planets. It's like I remembered it: the flipper fingers, the vogueing android, the shrug-bot on the side of the cabinet. The memories come flooding back.

I walk up to the machine and push the glowing start button. ♦

Nathan Weinbender is the Inlander's music and film editor. Although far from being a pinball wizard, reporting on this story reignited his love of the game, and he has half a roll of quarters in his jacket pocket right now. He can be reached at nathanw@inlander.com.