Credit the Pacific Northwest's music scene with inspiring the name of Washington State University's new exhibition, Indie Folk: New Art and Sounds from the Pacific Northwest.

"When I found out that the Northwest was a hub for indie folk, which is a genre that hybridizes traditional acoustic folk with contemporary instrumentation, I found a title for the show," says Melissa Feldman, the East Coast-based independent art curator who developed Indie Folk.

The music may have inspired the title, but it was the Pacific Northwest art scene that caught her eye several years ago when she lived in Seattle.

"I noticed that there was a lot of involvement with hand making and craft-based methods in the Pacific Northwest, as opposed to hands-off conceptual work, and a preference for rough-hewn, graphic directness that you could describe as 'folk,'" says Feldman, who worked with Portland-based Adams and Ollman Gallery in 2020 to stage Indie Folk online before approaching WSU with the exhibition.

Folk — as in folk music, folklore, folk hero — informally refers to people. It also implies a group of people's commonly held traditions. That might make folk art one of the easiest-to-understand categories of artmaking because it is of the people.

Although an individual's experiences with folk art may differ due to culture and history, there are commonalities in the form. Folk art exemplifies resourcefulness, like scrap-metal sculptures fashioned from old farm implements. It is often personal, narrative and sometimes functional, such as the heirloom quilt that conveys both the history and heritage of its maker and users. And folk art is graphic versus scripted, emphasizing authenticity over artifice; it may be created by someone who doesn't know or care about structured techniques, and who may or may not call themselves an artist.

As democratic as folk art sounds, however, the term is also problematic, says Ryan Hardesty, executive director of Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art WSU. "Historically it was used as a bit of a catch-all term for really — sadly — any artist that was viewed outside the traditional art historical canon."

Similar labels like "outsider art" or "low art" used in academic or other institutional settings have historically segregated artists — and therefore the art they produce — according to education, gender and ethnicity.

Indie Folk and exhibitions like it can help address those disparities.

"I think what's exciting about today and the world we're living in now is seeing an effort to kind of reclaim the term 'folk,' to work to dissolve some of those boundaries, giving greater value to wider forms of human artmaking and ingenuity," says Hardesty, who worked with Feldman since 2021 to bring Indie Folk to WSU.

Neither Hardesty nor Feldman would call the exhibition's participants folk artists in the traditional sense, and few, if any of them refer to themselves that way.

"Rather the point [of Indie Folk] is really to reflect on sensibilities, chosen aesthetics and influences of a select group of contemporary artists of the Northwest," Hardesty says.

Feldman concurs.

"None of the artists in the show are interested in reproducing early American wooden toys or a classic quilt pattern," says Feldman.

Although the artists in Indie Folk might not label themselves as "folk artists," they do reference folk traditions in various ways, Feldman says, including in terms of "aesthetics, formal and material inventiveness, connection to the past, closeness to human experience and ordinary life."

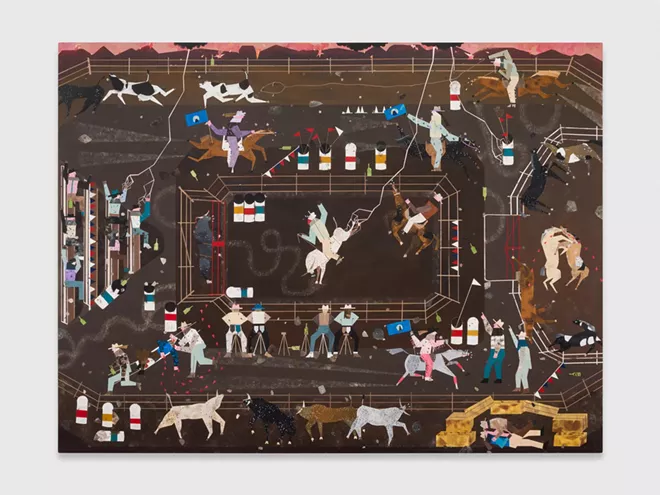

Aesthetically, Andrea Joyce Heimer's painting, "The Big Sky Rodeo Finals That Summer Were Marked By A Flash Lightning Storm, A Horse Fight, And My First Handjob In A Haystack," illustrates a complex outdoor event from both straight on and overhead so that viewers "read" the action almost like a graphic novel.

Vince Skelly's carved wooden benches and sculptures are a hybrid of two ways of working, featuring both rustic and highly refined surfaces and forms. His sculptures also bridge to the past, reminding of ancient monoliths, as well as the modern art those historical pieces inspired.

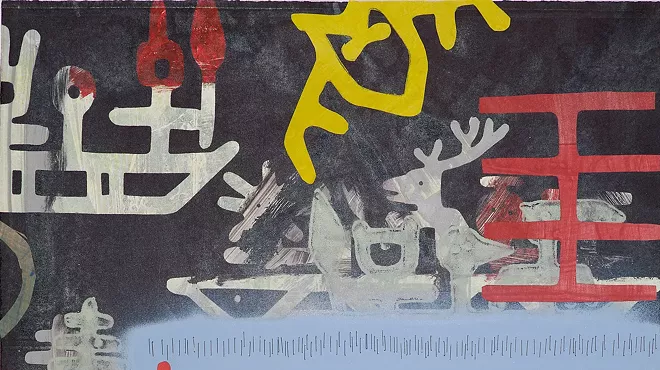

Denzil Hurley similarly steps in two worlds, says Feldman, who describes Hurley's mixed media pieces like "Glyph Frame #6" as sophisticated and modern from a distance, with its monochromatic coloration and minimalist composition. Yet Hurley also employs handmade objects in his work and — upon closer inspection — you can see his scribbles and brushstrokes, which are more related to folk traditions.

"The reason why he loved the language of art is it's more open and allows more ambiguity than the language of words," Feldman says of the late Barbados-born, Yale-educated artist who died in 2021.

Many of the Indie Folk artists incorporate common materials in uncommon ways, especially D. E. May, but also Marita Dingus, whose work symbolizes overcoming historical oppression.

"The discarded materials represent how people of African descent were used during the institution of slavery and colonialism then discarded, but who found ways to repurpose themselves and thrive in a hostile world," writes Dingus, in her artist statement.

Visually, Dingus' work seems fragile or fragmented, yet conceptually it is nuanced and cohesive, reminding viewers that the materials in contemporary folk art might be common, but the thought process is not.

Sky Hopinka's video, "Jáaji Approx.," shifts the focus away from inventive material usage in contemporary folk art and toward thematic commonalities.

Hopinka, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and descendant of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño people, juxtaposes a range of rural to urban landscapes with voice recordings of his father over a 10-year period. Superimposed over the imagery are transcriptions of the elder Hopinka's words in one of three languages: English using the disorienting yet familiar phonetic alphabet; English using the (conventional) Roman alphabet; and Hoak, the traditional language of the Ho-Chunk people.

On one level, Hopinka's work reflects similar themes throughout Indie Folk: family, community, oral and documentary traditions, rural sense of place, cultural traditions. On another level, it signals the continual evolution of the contemporary folk genre.

Indie Folk is not an endpoint; it's more of an exploration of the concept of folk, says Feldman, whose lifelong interest in art and curating has been fueled by travel and innate curiosity.

"I think my familiarity with art scenes in different places I have lived — which include London, Glasgow, [Washington] DC, Philadelphia, San Francisco and New York, where I'm from and return to regularly — gives me a basis of comparison and has sensitized me to difference," Feldman says. "With Indie Folk I'm trying to figure out where this trend came from to give some historical context for that."

Interest in contemporary folk isn't limited to the Northwest, she says.

Indeed, the American Folk Art Museum in New York City is celebrating its 60th anniversary with four different folk art exhibitions that will travel the nation through 2024. And when Indie Folk ends its Pullman run in May, it will travel onward to Schneider Museum of Art in Ashland, Oregon, and the Bellevue Arts Museum in Bellevue, Washington.

"I'm not the only curator these days looking at nonurban, nonmainstream, nonacademic sources and histories that affect art-making now," Feldman says. "I think there's a lot of interest in that." ♦

Indie Folk: New Art and Songs from the Pacific Northwest runs through May 21 at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art WSU, 1535 N.E. Wilson Road in Pullman. The show is free and open Tue-Fri from 1-4 pm, and Sat from 10 am-4 pm. For more information, visit museum.wsu.edu or call 509-335-1910.