Nikki Conley thought the Red Delicious apples growing on scraggly trees in the front yard of her Athol, Idaho, home would be mealy and tasteless like most store-bought fruit she'd known.

She was wrong.

"It reminded me of what they used to taste like when we were kids," says Conley, whose family relocated to North Idaho in 2016 on land east of Silverwood Theme Park, a stretch dotted with homesteads where the prairie gives way to national forestland. This new home, paired with that delicious bite into an old-growth apple, became the genesis of Athol Orchards, founded last year.

The Conley's 10-acre, semi-wooded lot is more of a mini farm than a full-fledged orchard; it's also home to chickens, pumpkins, flowers, bees and an old tractor named Leaky Pete.

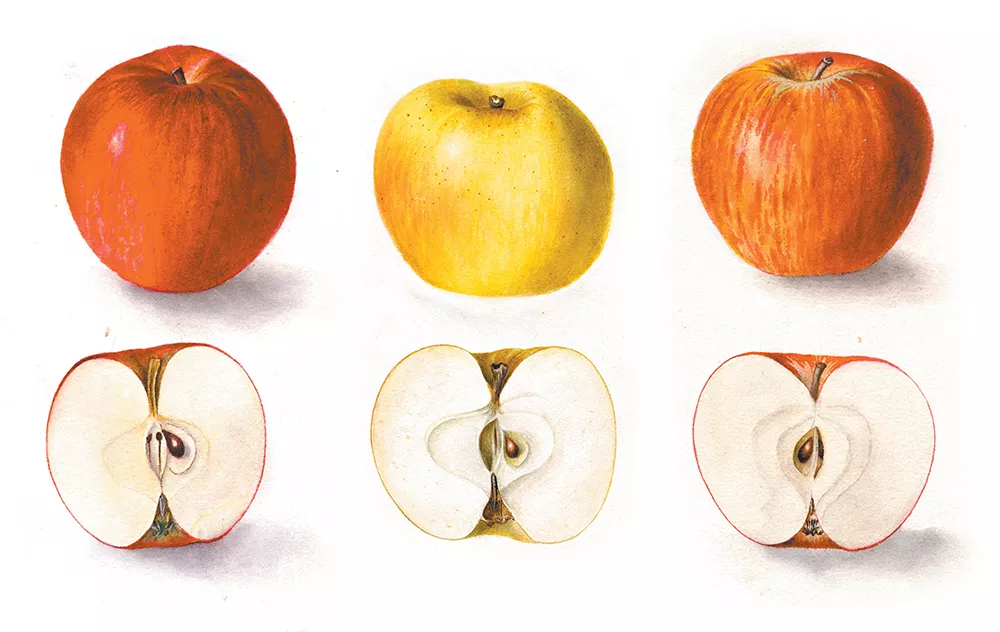

The family has since planted 50 new apple trees, including varieties like Yellow Delicious, Cortland, Winter Banana and Honeycrisp (Conley's favorite). They chose each tree for its distinctive traits, like high juice content, good eating quality or longer storage capability.

Until Athol Orchards can press its own cider (the trees won't produce fruit for several years), the farm locally sources unfiltered and pasteurized Honeycrisp apple cider, which they reduce to a molasses-like product Conley calls "apple pie in a bottle."

The orchard's spiced Apple Cider Syrup ($8/8 oz., $16/16 oz.) is good on barbecued meats or ham, in desserts and beverages, or anywhere a more complex sweet element is needed. Social media helps ensure Conley receives feedback about how customers are using the product, which she sells at Coeur Fresh Market, online at atholorchards.com, and at Kootenai County farmers markets.

Conley's newfound interest in her orchard's output and the regional history of apple growing also led her to Dave Benscoter, sometimes referred to as the "apple detective" for his research-based identification techniques and his prior career in law enforcement.

After helping a Chattaroy, Washington, neighbor with her trees, Benscoter became intrigued with determining the apple's specific variety, joining an exclusive group of people who hunt "lost" apples. Benscoter now works with the Whitman County Historical Society on the Lost and Heritage Apples of the Palouse Project, and occasionally gives talks on his work and discoveries, such as one he did for Inland Northwest Food Network this past November.

"The Spokane Valley consisted of hundreds of small orchards that banded together for purposes of marketing and selling," explains Benscoter, who's garnered national headlines for his discovery of a lost apple growing on the Palouse's Steptoe Butte.

"By the 1920s there were over a million apple trees in the Spokane Valley," he says.

Believed to have been brought across the pond by pilgrims, apples quickly proved to be a hardy crop for the New World. They're cultivated through grafting — joining a cutting of one plant onto a different plant so the two grow together — or by seed, including by the likes of historic figure Johnny Appleseed. Since European colonization of North America, apples have meant cider to drink or trade, and food through the winter for both people and livestock. The Red Delicious, for example, can grow to 25 feet tall, yielding up to 20 bushels of apples annually (around 800 pounds) that can be stored for up to six months.

Benscoter's focus on lost apples is no small feat given the fruit's sheer diversity. Of the estimated 17,000 varieties that formerly grew in North America, it's estimated as many as 13,000 have vanished, and with them a bit of history.

From his dogged research into catalogs and shipping records, plus a lot of shoe leather exploring orchards throughout Eastern Washington, Benscoter has helped reshape our understanding of how apples influenced Spokane — especially throughout the Spokane River valley spreading east from the city's core toward the Idaho Panhandle — which held court as Washington state's "apple capital" for a generation or so.

In 1908, for example, Spokane hosted its first-ever National Apple Show as the region grew, then besting even Yakima and Wenatchee. Fred Overley, Horticulturist Emeritus for WSU, estimates that the nearly 5,000 acres of apples and as many as 45 varieties grown around Spokane led to a thriving industry of growers, packers and shippers — the city's railroad hub was also paramount — until peak production in 1925. That year, he says, prices fell, the market was glutted and many orchard owners failed.

The Arcadia Orchard in Deer Park was once one of the largest in the region at 18,000 acres, though its sheer size led to its eventual demise.

The orchard's vestiges are still visible today in concrete road underpasses and the Dragoon Creek dam, as well as namesakes like Arcadia Middle School.

Aged remnants of many other commercial and private apple orchards dot the Inland Northwest's landscape, both in rural and urban areas. And until recently, many of these forgotten fruit-bearers' bounties had gone mostly unused, if but for foraging insects and animals.

"There are thousands of residential apple trees in Spokane County, and many of those apples aren't being used," says Nicki Thompson, who is a Harvest Against Hunger AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer with the local nonprofit Spokane Edible Tree Project.

Spokane Edible Tree Project's primary focus is coordinating volunteer gleaners to help harvest this unused fruit so it can be donated to food banks and community kitchens.

Last fall, roughly 50 volunteers helped collect nearly 5,000 pounds of apples from Resurrection Orchard, a rediscovered and restored historic orchard at the Episcopal Church of the Resurrection in Spokane Valley.

"A lot of people have inherited fruit trees upon moving to a new home, and don't quite know what to do with them. Many trees end up neglected," adds Thompson. "We'd like to raise awareness and provide tree owners with resources to learn about tree care."

In March, Spokane Edible Tree Project is partnering with the Inland Northwest Food Network and Episcopal Church of the Resurrection to host a class on apple tree grafting. The session also seeks to share apple scionwood, wood cut from an original tree being propagated, from its rare varieties in the orchard to help preserve and even resurrect apples that could otherwise be lost.

It's the type of event that the nonprofit hopes will attract people, like Conley, who want to know more about apples and their deep ties to our region — in history, economy, agriculture and community culture.

"My No. 1 thing is history and teaching," says Conley, whose past careers include graphic design and photography, as well as a few years teaching elementary school. Now she dreams of turning Athol Orchards into a teaching farm.

In the near future, she says Athol Orchards plans to partner with University of Idaho Extension and U of I Master Gardeners for hands-on classes on historic apple trees and cultivars, among other topics like beekeeping.

In the meantime, she'll be savoring the sweet success of her Apple Cider Syrup, which is helping sustain her family just as apples have done for so many others throughout history, and keeping an eye on her trees for the first blooms in spring. ♦