Menus are usually the first interaction a diner has with a restaurant. They used to be posted on windows to draw passers-by in. Today, they're posted on websites to draw hungry diners scrolling Google. At the table, trifolds, fresh sheets, clipboards, cardstock and QR codes all tell you what to expect from your meal — not only from the food, but also from the vibes and even values of the eatery.

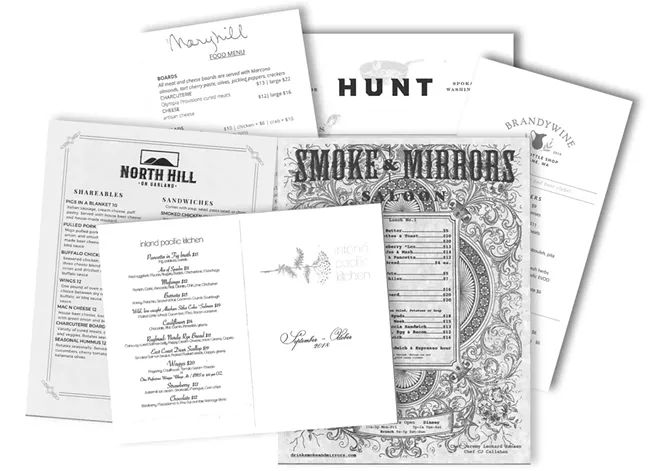

Arts and Culture Editor Chey Scott spent some early years at the Inlander as a food writer. In the late 2010s, she collected menus from new and existing spots around town and, thankfully, saved them. A manila folder on her bookshelf became a tiny time capsule of the Spokane restaurant scene, and a great boon to a new food writer.

A walk down menu memory lane reminds the Inland Northwest what we've lost and what has remained the same. With over 800 restaurants in the area and about 60 menus in our time capsule, there are sure to be exceptions to the patterns we found. But the New York Times recently tried to analyze the whole country's dining scene with 121 menus total, so I'd venture to say that our ratio is a little bit better.

WHAT WE'VE LOST

HUGE MENUS

We all like options, but... 92 of them? Unfolding a giant pre-pandemic menu from MAX at Mirabeau unleashed almost 100 appetizers, entrees and desserts at me, not counting drinks. A smaller but just as dizzying Europa menu crammed 62 items front and back on a piece of yellow computer paper.

Although these stalwart establishments may be able to keep up with their neverending entrees, most newer restaurants started trending the opposite. Menus across Spokane started shrinking as chefs focused on fewer, quality over quantity regular offerings. Jeremy Hansen's Biscuit Wizard offered just biscuits — although that might have been too small, as it closed in 2019. Seems like menus somewhere in the middle hit just right.

LUNCH SPECIALS UNDER $10

Yes, we all know dining out is getting more expensive. But seeing a 2017 lunch special at Phonthip Thai for $9.95 was like rediscovering a favorite childhood toy. Sometimes it seems like life will never be that good again.

In our time capsule, plenty of decent lunch and dinner entrees were at or under $15. Like the Oaxacan black beans and eggs at Mizuna with mole and corn tortillas for $14.95 in 2019, fettuccine alfredo at the Beryl (before it became the Barrel Steak and Seafood House in 2016) for $10, and the Student Loan grilled cheese at Perry Street Brewing for $5 flat.

Now it's hard to find a lunch special under $15. Plenty of factors are at play, like rising food costs, rising minimum wage, higher rents, plus fees and taxes. But plenty of people still have student loans — any chance we could get some of those cheap student loan sandwiches back?

SINGLE-USE MENUS

If COVID hadn't killed this, the environmentalists probably would have. It seems like a stellar idea — individual single-use paper menus with a check box next to each item, so guests can check off exactly what they want, and servers can drop it off at the kitchen. TT's Brewery and BBQ surely wasn't the only spot to implement a trendy new ordering style in the late '10s. Cut down on mistakes and save servers' sanity? Sign me up!

Well, maybe. Passing around communal pens and handing off the piece of paper someone just used to cover their cough probably wasn't the move during a global pandemic. Plus, ink and paper ain't cheap. I think there are plenty of good reasons why this style of menu didn't stick around long in Spokane. And plenty of good trees that are thankful, too.

FONTS

For a futuristic look, or perhaps ease of reading, higher end menus started dropping serifs — the little bits of typeface that decorate the ends of letters in fonts like Times New Roman or Garamond. If you're not a nerd who's already embroiled in the serif vs. sans serif debate, think of dropping serifs as a prophecy of what was about to come: an overreliance on online menus, which are predominantly sans serif.

Serifs were usually used on menus at family-style restaurants or classic American steakhouses. Trendy, cutting edge places, or at least places trying to be cutting edge, ditched the extra clutter. A nod to digital life, sans serif menus seem to pander to the crowd surfing their phones for a hot new experience to out-Instagram their friends.

FULL SHEET TRAYS OF FOOD

Specific menu items come and go, which means we get to return to familiar places and have new experiences. Sometimes, though, the past knows best. Like the $8 sheet tray of chocolate chip pancakes for brunch at North Hill on Garland from 2018. I personally think we should go back to serving entire sheet trays of food. Especially pancakes. Just a thought.

WHAT WE HAVEN'T LOST

CAESAR SALADS

This was my first observation, and the first for the NYT analysts, too — the Caesar salad is unkillable. Classic Caesars. Grilled Caesars. Caesars with optional crab. It's so uncontested, it's sometimes the only option for salad. It's been on almost every menu I've seen. It doesn't seem to be going anywhere soon.

I get that the dressing is a perfect lesson in emulsification and one of the only ways people will eat anchovies. But, seriously? Can't we get something other than Romaine doused in lactose, gluten and sodium? Salads should get the chance to be fun and creative, too. I'm calling Brutus.

SIGNAL INGREDIENTS

"Virtue signaling" is a term for saying or doing something that acts as shorthand to let other people know you're part of a certain group, like putting a sign in your lawn or using a hashtag on social media. After going through some menus, I think there's such a thing as ingredient signaling, too — ingredients that make the foodies raise their eyebrows and think they're about to get something high end and unique.

Pork belly, Ahi tuna and rye flour started to seem like "signal ingredients" after being featured again and again in dishes that were experimental or trendy. I'm not mad about it — they're definitely delicious, and I'm all for supporting good protein and dark grains. But considering how often they're actually used, they may not signal "in-crowd" as much as we think.

SHARING

Appetizers. Small Plates. Lil Bites. Tapas. There's plenty of ways to name the tiny dishes that always start off a good evening. But by far, Spokane menu designers prefer the nickname "shareables." It's endearing, I think, to assume I'm gonna order chips and guac and not keep the whole thing to myself. Or maybe I'm surrounded by people who do genuinely love ordering for the table. Either way, it's lovely to be in a city so focused on sharing. Let's never change.

TRYING NOT TO SAY "SANDWICH"

Look, I get that you want your restaurant to be unique. And I appreciate that you want your language to be precise. But please, don't make things more complicated than they need to be.

Inland Northwest menus have tried for years, and are still trying, to come up with new ways to describe sandwiches for no apparent reason. Handhelds? Maybe. On A Bun? Stretching it. Between Bread? Meats in the Middle? There's just no need. For the love of all portable foods, just call them sandwiches and move on. If you have a list of sandwiches and a wrap sneaks in there, I'm not going to be upset. I get the gist.

MENUS!

Despite plenty of places around the country setting tables with QR codes, the Inland Northwest has remained staunchly attached to old-fashioned, analog menus. I think that says something about our commitment to quality service and personal touch. I get to keep stuffing our time capsule because our cities value the unique, the tactile, the communal. That's a great legacy to leave behind. ♦