It's calving season at Owens Farms. Every spring, Justin Owens brings his cows into the barns to give birth on clean, soft hay. In early April, a few calves are already here. A bull calf born just hours before tromps around the indoor courtyard, umbilical cord still trailing from his middle, strengthening his legs and testing his buck until he lies down for a suckle and a nap.

Most births happen early in the morning before Owens or his ranch hand, Brian Lee, arrive at the farm. Cameras in the barns are linked to their phones so they can keep an eye on the new mothers from anywhere. They're expecting 60 to 70 calves this year. It's a precious season for the herd, some of whom spent years as frozen embryos before coming into this life on the Palouse.

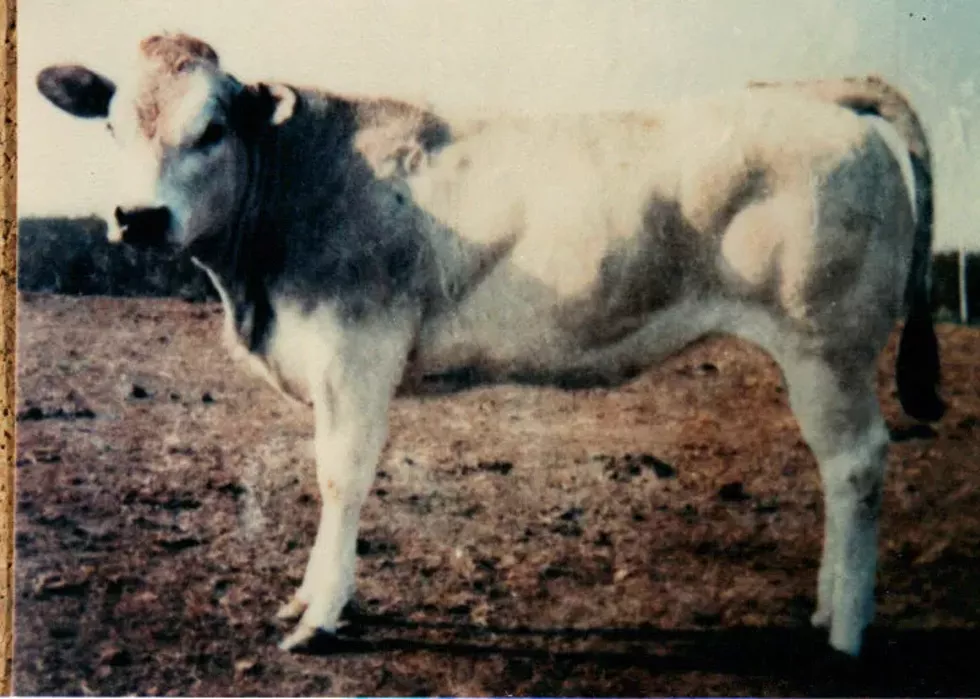

Owens Farms raises Piedmontese cattle, an ancient Italian breed that wasn't allowed outside Italy until 1979. Each animal naturally packs on more muscle than a typical Angus, and the beef they produce seems too good to be true — more tender than wagyu but as lean as salmon, protein packed and nutrient dense, high in the good kinds of cholesterol and low in the bad. It's an athlete's dream.

Gary Owens, Justin's grandfather, was one of the first ranchers to introduce Piedmontese to North America. He started raising a herd of the imported white cattle on the Palouse in the 1980s. When he stopped working in the early 2000s, he froze full-blood Piedmontese embryos so their perfect pedigree could continue long after he was gone. Today, Owens Farms' entire herd is built from those embryos, with genetics that trace back to some of the first cows to leave the foothills of the Alps.

To have a little bull calf come out with no muscles on his rear end, and three months later he looks like Arnold Schwarzenegger...

Owens Farms continues Gary's mission to promote Piedmontese to ranchers and chefs alike. In 2013, Justin resurrected his grandfather's herd and decided to be a stock breeder, hoping to help ranchers produce more, healthier beef by crossbreeding or transitioning to full Piedmontese herds.

"I want to see more ranchers raising full-blood Piedmontese because it's the best financial situation for them," Justin says. "They're the most efficient animals, they produce the most meat with fewer resources, and it's a higher quality meat. But their question is always, 'Where's the end market?'"

To answer that concern, Justin is now also the owner of Manzo Piedmontese, a private beef label that's making its way through circles of the rich and famous. At about $100 per pound, Manzo's pure Piedmontese beef is a luxury item reserved for celebrity chefs and professional athletes — think the Denver Broncos, the defending Super Bowl Champion Kansas City Chiefs, or Dena Marino, personal chef to LeBron James, all of whom have bought, eaten, or cooked with Manzo beef.

"There needs to be that flagship product, in the same way that the Japanese government decided Kobe beef was going to be the flagship product for wagyu products," Justin says. "Manzo needs to be the flagship product for Piedmontese."

If wagyu eventually made it from Japan to Costco, maybe Piedmontese can trickle down, too. Half an hour from downtown Spokane, Owens Farms is trying to transform the American beef industry one calf at a time. It's a big dream for a few baby cows. But the Owens family knows a thing or two about defying the odds.

HORSESHOES

Gary Owens' parents were "Okies," refugees from the Dust Bowl who left Oklahoma and headed West to find work. Instead of stopping in the fields and orchards of California, the Owens headed up to Eastern Washington.After settling first in Malden, one uncle ventured even farther north. He started leasing a plot of land just south of Spokane near Hangman Creek, now called Latah Creek. The rest of the family joined him, and two twin boys were born in Spokane: Gary and Larry.

A traditional Americana story ensued. Gary and Larry were star athletes in high school, where Gary met his sweetheart, Jo Ann Carlson. He dropped out of Washington State University after a single semester to marry her.

He took up managing drive-in movie theaters and discovered a talent for business. He bought an A&W franchise, then started a construction company to build another one, eventually creating an A&W empire across Eastern Washington. He ran concessions for Expo '74, and partnered with a few other local businessmen to convert the Knickerbocker and Cambridge Court buildings into hotels for Expo visitors.

He bought land on the Palouse in 1969 to fulfill a boyhood dream. At that point, he had so much income his accountants recommended he find some depreciating assets to take him down a tax bracket or two.

Gary took the opportunity to start a racehorse stud farm. It was supposed to be a fun way to lose money. But thanks to a little luck and a penchant for genetics, Owens Farms became one of the most successful stud farms west of the Mississippi. One friend gifted Gary a horseshoe worn by Secretariat, racehorse royalty, which still hangs on the wall at Owens Farms.

But Washington horse racing started to decline in the 1980s, so Gary sold his racehorses with plenty still to do in the restaurant business. But the phone started ringing and wouldn't stop. A rancher out of Utah had a new idea for the farm.

"He knew Owens Farms from the horses," Gary said in a 2021 conversation with his grandson. Justin recorded a few long conversations with Gary before he died.

"He kept calling and saying, 'Gary ought to consider these Piedmontese cattle.' Jo Ann got tired of him calling and said, 'You got to call this guy.' So I called him, and he's telling me about Piedmontese — how they're lean and have very little fat on them, but they're tender, the most tender beef breed walking around."

The cattleman's promises seemed far-fetched to Gary. But he called the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Nebraska, which confirmed the claims. So Gary decided to take a look for himself and headed up to visit a herd in Canada. What he found there would put his business savvy and genetic expertise to the test.

THE GOOFY PART

About 25,000 years ago, white cattle from Pakistan migrated west. Eventually, they hit the Alps and couldn't go any farther, so they started romancing local European cattle. The result, thousands of years later, are several breeds of white Italian cattle, according to the Italian National Association of Piedmontese Cattle Breeders (in Italian, known as ANABORAPI).There's a bias in the U.S. beef industry against white cattle, Justin Owens says. Light-colored Brahman and Zebu cattle are popular in South Asia for their hardiness and heat tolerance, but they're also known for producing lean, tough meat. Popular thinking in American ranching teaches the lighter the color, the worse the meat.

Italians, however, think differently. After crossbreeding with European cattle, ancient Italian breeds like Chianina and Piedmontese retained the light color and leanness of their Asian ancestors, but still produced the tender muscle and rich milk of their Alpine roots. Italian lore says that Piedmontese beef was so tender, Italian butchers could trick customers into buying meat from an 8-year-old cow in place of veal. Northern Italians were so protective of their near-perfect breed that they wouldn't allow exportation of live animals or embryos.

That is, until the Canadians came knocking. Much to the dismay of Piedmont ranchers, an Italian man who married a Saskatchewan woman had been evangelizing throughout rural Canada during the 1960s about the merits of Piedmontese. He finally convinced the Ministry of Agriculture by showing them a picture of a jacked Piedmontese bull rippled with almost twice the amount of muscle the Canadians were used to seeing, according to Gary.

In the mid-1970s, Canada asked if Italy would share. Italy said no. And continued to say no for years, until the perfect storm of a worsening Italian economy and persistent Canadian politeness resulted in the sale of five Piedmontese to Saskatchewan in 1979: a bull named Brindisi, and four cows named Banana, Biba, Bisca and Binda.

"The goofy part was to introduce them to North America, they'd take them to Glentworth, Saskatchewan," Gary said in one of his taped conversations. "You can't hardly get to there from anywhere. To start a breed in North America and put it in Glentworth, Saskatchewan — they couldn't have buried it in a better place to hide it."

Nevertheless, Gary visited Glentworth three times to look at the new breed. He bought some semen and artificially inseminated a few of his Simmental cattle in 1987. Calves that were half Piedmontese showed immediate, impressive improvement in muscle gain, he said. So the next year he bought a few embryos and implanted those in his cows. Gary and his neighbors were startled by the results.

"To have a little bull calf come out with no muscles on his rear end, and three months later he looks like Arnold Schwarzenegger," — it shocked every Washington cattleman he knew, Gary said.

But the biggest mystery surrounding the breed, more than just the sheer amount of muscle, was the tenderness of the meat. Conventional thinking preaches that fat makes beef tender, Justin says. The connective tissue that binds muscle together is the enemy of tenderness, but fat that's marbled throughout the muscle breaks up that connective tissue and makes the meat softer.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture grades beef almost exclusively on the amount of marbling it has. But according to a study done at the USDA's Meat Animal Research Center, Piedmontese had the second-lowest amount of fat among 11 breeds, even though it was the most tender. Meat scientists were puzzled. How was it possible that Piedmontese beef was so tender yet so lean?

GROPPA DOPPIA

Around the same time the Meat Animal Research Center was doing research, scientists in Belgium were struggling to understand why Belgian Blue cattle, another white cattle breed from Europe, were so muscular. They published a few papers suggesting a theory that a "major gene is involved in the determination of muscular hypertrophy in Belgian Blue cattle." That is, the cows weren't bulkier because of feed or environment, but because of a certain genetic disposition.By 1997, researchers Alexandra McPherron and Se-Jin Lee at Johns Hopkins University had nailed down what that genetic disposition was: inactive myostatin.

Myostatin is a naturally occurring protein in many birds and mammals, including humans. It's a growth inhibitor that bonds with other proteins that you eat to stop some of it from turning into muscle. From an evolutionary perspective, it's probably a good thing — for animals that need to be fast and mobile to run away, being super yoked isn't all that great.

Deactivating myostatin could hold solutions for muscular dystrophy, McPherron and Lee hoped. For ranchers, it's also a super handy trait in beef cattle. A few animals naturally have myostatin completely "turned off," as Justin Owens puts it, and Piedmontese cattle are one of them.

No pun intended — it's a different animal. The fact that it has no fat, if you're not careful with it, you're screwed.

Nearly all the protein that Piedmontese cattle eat goes directly into making muscle. That muscle is usually most visible in their huge hindquarters, which earned the nickname "groppa doppia," or "double rumped." Not only is there more muscle, but inactive myostatin also means that the muscle fibers are smaller and more tightly packed together. Smaller muscle fibers significantly reduce the need for connective tissue.

Think about filling a vase with flowers. The vase is the muscle sheath, the stems are muscle fibers, and the space between the stems is connective tissue. The thicker the stems, the fewer flowers and more space between each one. But if you fill it with thinner stems, you can pack it much more tightly and eliminate most of the space. Inactive myostatin simultaneously makes the muscle, or the vase, bigger, while making the muscle fibers, or the stems, smaller.

Since there's very little connective tissue, the huge muscle stays tender. There's no need for fat to interrupt anything — thus, incredibly tender meat without any marbling.

The discovery of inactive myostatin gave Piedmontese ranchers a scientific answer to back up their personal experience. But the technical explanation still cut deep against traditional thinking in the beef industry, so many cattlemen remained skeptical. The discovery, however, played directly to Gary's strengths. He was used to thinking about genes after breeding racehorses for years. Suddenly, tracing genetic traits in cows seemed obvious.

To maintain a registry of full-blood Piedmontese in the U.S. and Canada, Gary and his friend Vicki Johnson, a Saskatchewan rancher, started the North American Piedmontese Association, or NAPA. It was the first cattle registry to be based on the presence of a genetic variation, the inactive myostatin gene.

Through NAPA, Gary was helping preserve the Piedmontese breed for generations to come. He was also harvesting and freezing embryos from some of his favorite pairs, with the hopes that good breeding and responsible registration would ensure the highest quality Piedmontese for years to come.

A DIFFERENT ANIMAL

Justin Owens spent half his childhood on his grandparents' farm, half in his grandfather's restaurants. His grandpa was his best friend and mentor, so Justin always assumed he'd end up working in restaurants. He was allergic to alfalfa, after all. He studied business management and economics at Eastern Washington University. Well groomed, welcoming, and relaxed under pressure, Justin might've been a great maître d'.But when one of his grandfather's bulls sold for $10,000, Justin's interest in cattle was piqued. He realized the precious resource and potential he had on his hands — well, in the freezer. He got "sucked back" into livestock agriculture, he says, and began in earnest in 2013 to restart a herd from the embryos that had been frozen for years.

Today, there are about 300,000 Piedmontese in Italy, and about 6,000 full-blood Piedmontese in the U.S. About 100 of them are on Owens Farms. For comparison, the USDA estimates there are about 28.2 million beef cattle in the U.S.

This summer, Justin and his ranch hand Lee will move the herd through the forests near Krell Hill, where the cows forage and help take care of the land. After a deep dive into Piedmontese-specific nutrition, Justin supplements their diet with alfalfa,Timothy grass, peas, barley, and grape pomace, all sourced from less than 10 miles from his ranch.

While the cows are on the mountain, Justin's young bulls lay down in a fenced pasture, calm and docile with dark circles around their deep, black eyes and heavy eyelashes.

"They're like big puppies," Justin says. One-ton puppies, to be exact.

In his affection, Justin might have gone a little over the top to provide the best quality of life for his herd — a "Club Med for cows," as he calls it. In addition to the bountiful rolling hills of the Palouse that make up the ranch, Justin built a huge barn to dairy cow standards, which require more room per animal than typical beef barns. For now, he doesn't want any more than 100 cows. It's what the land can accommodate, and he doesn't want to give up the level of care that he can provide by knowing each cow's name and personality.

"I still haven't quite come to terms with having a beef label," he says.

But he does have a beef label, and Manzo is starting to get some major recognition. With the help of chef Joe Bonavita, executive chef of Salt 7 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Manzo earned a spot at the star-studded Food Network South Beach Wine and Food Festival.

"We decided to do a steamship round, which is basically just above the knee all the way up to the rump," Justin says. "A normal steamship round is 45 or 50 pounds. The final one that we sent was 95 pounds. Definitely something that stopped people in their tracks. All the chefs wanted to come over and take pictures of it."

Bonavita and Manzo are returning to Florida this May to be featured in a private suite at the second Formula 1 Miami Grand Prix. The Denver Broncos bought 1,100 pounds of Manzo beef for their preseason meals. Closer to home, head golf professional at Manito Golf and Country Club, Gordon Corder, took up a "carnivore challenge" and ate Manzo beef almost exclusively for over two months.

If Manzo is ever dismissed, it's usually because it's misunderstood. Without stereotypical marbling, a cut of Piedmontese beef looks more like the smooth, raw flesh of a fish, and cooks in half the time of conventional beef.

"To be honest, I didn't really give too much credit to [Justin]," says Chad White, chef and owner of Zona Blanca Ceviche Bar and TT's Brewery & Barbecue, who started experimenting with the meat a few years ago.

"Because in barbecue, I'm always looking for fat and lots of marbling. Blood and fat are where flavor comes from. So I took the steak home, I cooked it up, I overcooked the shit out of it because I didn't understand it. I treated it like how I would any ribeye steak or New York steak. So I didn't revisit it for really the longest time."

When White tried again, he paid more attention to Justin's instructions.

"He showed me what some of the chefs in Italy were doing, where they're basically doing Piedmontese sushi," White says. "Slicing it very, very thin, putting it on rolls, on rice or whatnot. And I thought, 'How great would it be to showcase this incredible product raw on the plate?'"

With this new vision, White put Manzo beef tartare on the menu at Zona Blanca. He's also been putting in the time to learn the best uses for different cuts. For someone who knows beef inside and out, it seems unnecessary. But most chefs agree that Piedmontese requires reeducation.

"No pun intended — it's a different animal," says Spokane chef Tony Brown, who hosted an event at his restaurant Ruins to help launch Manzo last August. "The fact that it has no fat, if you're not careful with it, you're screwed."

"It's like venison or rabbit," adds Peter Adams, a chef at Ruins who co-hosted the launch party. "But when you eat it, because it's got like two or three times the amount of protein, your gut really feels like you've eaten a lot."

But it's not the kind of full that makes you feel bad, White says. Take it from him — he spent time learning butchery in Japan and ate his fair share of wagyu, which, if "you eat too much of it, you'll feel like shit," he says. "You don't feel like that when you eat [Piedmontese]. So for athletes that are looking for lean protein, it's probably really good."

Last year, Justin Owens was featured on Adam Morrison's podcast, The Perimeter, talking all things basketball and beef with the retired Gonzaga and NBA star. Meanwhile, Justin O'Neill, a new business manager for US Foods and consulting chef for Manzo, has been instrumental in getting the beef into the hands of other local chefs like Joe Morris, Jarrott Moonitz, Adam Hegsted, Travis Tveit and Cara Anthony.

Later this year, locals will have another opportunity to try Manzo, when Owens Farms hosts Dinner on the Farm, a Sept. 13 fundraiser for the Women and Children's Free Restaurant and Community Kitchen.

There's still an almost impossibly long road for Justin, his new calves and his tiny Italian cattle herd to make a meaningful impact on the American beef industry. But Owens Farms is undeterred.

"My grandfather had zero compromise in what he thought was the right thing to do," Justin says. "If it can be done, it's worth doing." ♦