Budding bicyclists thread between orange cones and bump over obstacles at a recent community bike rodeo in an empty Pullman parking lot. Older riders bunny hop their bikes and pop wheelies as organizer Scott McBeath circles offering encouragement.

"Nice!" he calls to a pint-sized pedaler steering through the course.

McBeath leads a series of bike camps for Pullman Parks and Recreation each summer, teaching children as young as 3 how to bike safely. As his riders improve, they advance to jumping off ramps, descending rocky trails and navigating city traffic.

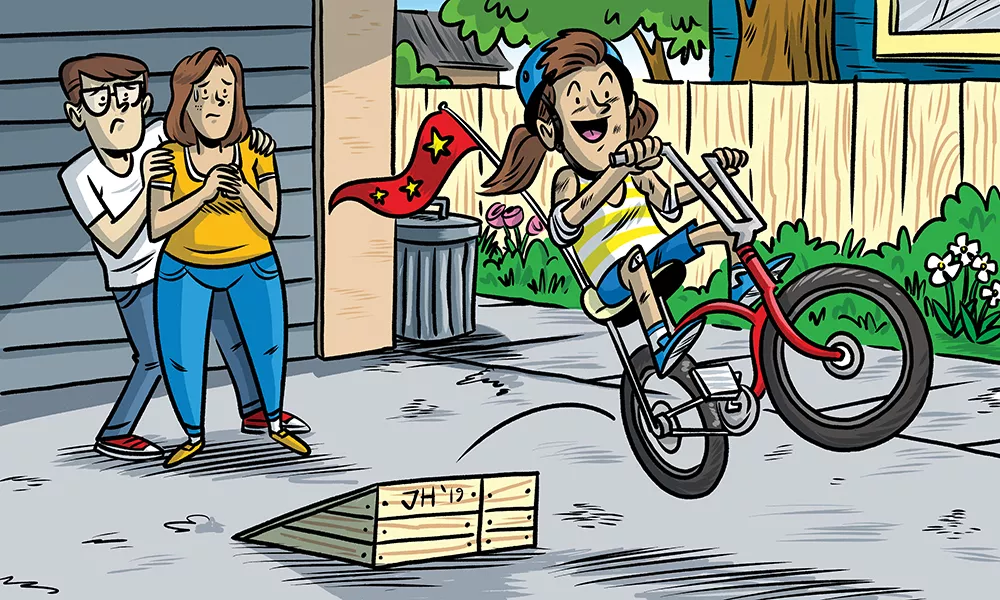

Biking can exemplify the childhood connection between risk and responsibility. How fast is too fast? Is this move too difficult? Will someone get hurt? Parents fret over toddlers scaling the monkey bars or teens out late at night. They hover, scold and babyproof.

How do you let a child test boundaries without jeopardizing safety?

Just like biking, it takes balance. Not all risks are bad, researchers say. Beneficial risks can help boost confidence, build camaraderie and develop self-awareness. Confronting fear and failure instills resiliency. Somewhere between "free-ranging" and "helicoptering," parents can guide kids toward taking smarter risks.

"You're teaching them how to ride," McBeath says of biking. "You're [also] teaching them how to be independent and make decisions for themselves."

Elizabeth Weybright, an assistant professor at Washington State University, studies adolescent development and risky behavior. She explains that as children grow, they often seek out novel experiences that push limits or result in rewards. That can range from climbing trees and underage drinking to healthy challenges like public speaking and taking on difficult leadership roles.

"They're learning what it's like to fail and how to deal with that and move on."

As their brains develop, she notes teens sometimes acquire physical skills and strengths before they mentally grasp the consequences of their decisions.

"They don't necessarily have those abilities to think through what might happen," she says. "It's like having a car with all gas and no brake."

Weybright says her research also indicates that boredom, risk-taking friends and poor supervision tend to increase dangerous behaviors such as substance abuse.

Experts recommend talking with kids — at any age — about the objective hazards they encounter during risky activities. Go through potential outcomes and consequences with them. With grade-schoolers, that might be talking about the dangers of playing near the street. With teens, that might mean discussing the repercussions of drugs or unsafe sex.

Weybright suggests asking older kids about whether their actions align with their personal values and keeping track of who they hang out with. She says parents can offer a secure and honest perspective that encourages self-reflection.

"There's also a benefit in doing things that don't go well," she says. "They're learning what it's like to fail and how to deal with that and move on."

Many experts suggest time in the outdoors can provide healthy opportunities to discuss potential hazards and decision-making with children of all ages. Maya West, a teacher with the Urban Eden Farm School in Spokane, says their 3-6 year olds spend all of their time outside on the organic farm, exploring their own limits and interests.

The kids can scramble over logs, gather around a fire ring, help harvest vegetables and splash in the nearby creek. West says staffers rarely forbid a child from trying something iffy, but they ask questions to help clarify the potential consequences.

"We trust that children are capable of driving their own learning," she says. "We're always looking out for their safety, but we're allowing them to take risks so they can learn."

West says she will introduce children to risky tasks, like using sharp scissors, by modeling it for them first and then setting strict rules for responsible behavior.

"There are boundaries," she says. "If they're not using it safely, they don't get to use it. Those tools do need to be... respected and treated appropriately."

West and others argue that allowing children to take small risks helps them learn to trust their own judgment and develop their physical awareness. Offering the room to take risks can empower them to take ownership of their decisions and behaviors.

Many children suffer serious injuries from car crashes, West notes, but the parent who prohibits skateboarding or hunting probably doesn't think twice about driving them around in a car because they consider it a necessary risk.

"Letting children take risks and make choices and make mistakes is just as important to their development and just as necessary as riding in a car," she says. "Without that, they're not going to develop into as strong and well-rounded and resilient of individuals."

During a recent bike camp, McBeath escorted a dozen young riders through the streets of downtown Pullman. Before such an outing, he will run the group through traffic scenarios on a chalkboard and ask them about how to handle different hazards.

"What will happen if you did this or did that?" he explains. "When we're riding, we also do lots of stopping and talking about what's going to happen."

McBeath says he tries to get them to anticipate risks so they can manage them. He's trying to arm them with experience. And he's having faith they will rise to the challenge.

"Kids year after year come to me and say, 'Thank you for teaching me freedom,'" he says. "I love seeing kids ride and seeing kids progress. They really mature and grow."