Thanks to films (and novellas) like A River Runs Through It along with historical figures like James A. Hensall waxing eloquent about the way it calms "over-taxed brains and wearied nerves," fly-fishing has become synonymous in the popular imagination with serenity and meditation.

Tom Rosenbauer isn't having any of it.

"I hate hearing the term Zen used in relation to fly-fishing," he says. "It's not meditative."

Rosenbauer is one of the most respected anglers in the contemporary fly-fishing scene. Having authored books like Fly Fishing in America and Casting Illusions: The World of Fly-Fishing, not to mention numerous guides for the specialist sporting goods retailer Orvis, the same company for which he also hosts a long-running fly-fishing podcast, he's heard all the stereotypes about the sport and knows how they diverge from his firsthand experience.

So what exactly is it that makes fly-fishing, in Rosenbauer's words, "all-consuming?"

To start, it might help to understand what it is and how it differs from other types of angling.

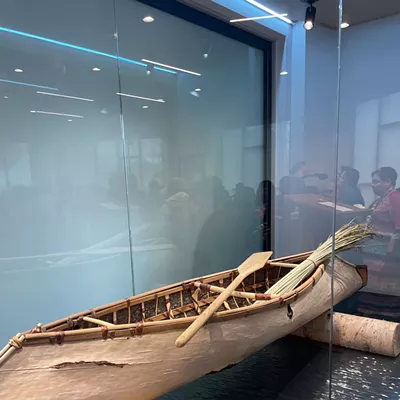

Fly-fishing, as its name suggests, makes use of an artificial lure — as opposed to live or processed bait — that typically resembles an insect. It's distinct from spin fishing, which also uses lures, primarily because of the equipment and the technique the angler employs to cast the ultra-lightweight fly into the water. There's also some puppeteering involved. The angler has to make the fly seem lifelike enough to dupe predatory carnivorous fish like salmon and trout into thinking it's a snack.

"In fly-fishing, you're not sitting in a boat or on the bank ruminating on life or gazing at your navel, waiting for a fish to bite. You're always moving, you're observing. You need to notice the way the water flows, the way the currents move. You need to notice the insects that are hatching. Even the birds along a stream can tell you when the insects are hatching," Rosenbauer says.

It's this perpetual state of alertness and engagement with one's surroundings that, to him, not only define the art of fly-fishing but also contribute to its positive effects on well-being.

"Our bodies are tied to our minds. And when you're fly-fishing, you're often using your balance wading in a stream or standing in a boat. Here you are, out in nature, you're active, you're moving, you're occupying your mind, you're trying to solve problems. What about that couldn't be good for your mental health, right?"

Rosenbauer laid out some of these mind-body benefits in a resource guide titled "Orvis Guide to Family Friendly Fly Fishing." In it, he talked about some of the sport's therapeutic qualities and how they're leveraged by national groups like Casting for Recovery. That nonprofit organization, founded nearly 30 years ago in Rosenbauer's native Vermont, provides a way for breast cancer survivors to come together and engage in the healing that fly-fishing offers through its corporeal activity, mental focus and camaraderie.

Casting for Recovery states that over 11,000 women across the country have taken part in its program since its inception. And for men who are living with or recovering from cancer, the slightly newer organization Reel Recovery draws on the same holistic benefits of fly-fishing. Following the motto "Be well! Fish on!" it has hosted around 4,500 participants at over 400 retreats.

One group that has experienced both anecdotal and clinical benefits from fly-fishing is veterans. A study that Rosenbauer refers to in the Orvis guide examined Iraq War veterans with missing limbs who were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). After just a single weekend of fly-fishing, researchers found that the veterans had "significantly reduced" levels of cortisol, a hormone associated with stress. They also reported better sleep patterns and decreased fear and anxiety.

Lest that study seem like a one-off, Project Healing Waters has fashioned its entire mission around helping active military service personnel and veterans tap into the curative aspects of fly-fishing. The nonprofit served more than 6,000 participants last year alone through chapters located all over the United States — including ones in Spokane and Coeur d'Alene.

As a testament to just how effective the sport is now considered for treating war-zone PTSD, the 2022 film Mending the Line distilled these veterans'collective fly-fishing experiences down to a small ensemble cast and translated the story of recovery to the big screen. With fly fishers numbering around 7.8 million in the United States, according to a 2021 report from the Outdoor Foundation, a film like Mending the Line would seem to have a built-in audience.

An Ancient Practice, Now a Therapeutic Sport

Although its origins likely lay in sustenance rather than recreation, the use of artificial fly-like lures to hook fish is a practice that dates to antiquity. Mentions of fly-fishing were recorded nearly 2,000 years ago. One oft-quoted passage from De Natura Animalium by the Roman author Aelian provides a detailed account of Macedonian anglers'equipment and technique.

"Then they throw their snare," he wrote, "and the fish, attracted and maddened by the color, comes straight at it, thinking from the pretty sight to gain a dainty mouthful."

Through the centuries, more writers would extol the art of fly-fishing as well as the perks enjoyed by its practitioners. The aforementioned James A. Hensall described fly fishers as "brain-workers in society ... drinking deep of the invigorating forces of nature."

More recently, in a Paris Review article titled "The Philosophy of Fly-Fishing," John Knight wrote, "I find great solace in the sport. I delight in a day on the river, noticing all its features, trying to join its small dramas. Rarely do we have the excuse to sidestep the human perspective and become something else in a place where the only currency is camouflage and politics are straightforward."

In the here and now, Melissa Ceren continues to add to that sizable body of fly-fishing literature. She's a Colorado-based fly-fishing guide as well as a licensed professional counselor who writes on the sport's natural intersection with mental health.

Ceren cites a "confluence of factors" around fly-fishing specifically that can contribute to psychological well-being. The strong sense of community, for example. Plus the mindfulness and whole-body movement emphasized by Tom Rosenbauer. But she also points to the sport's adversity as a means of building self-confidence.

"I see fly-fishing as a microcosm of how life is on the outside. Like with any skill, it's not automatically easy. You have certain challenges, like getting knots in your line or losing flies, which cause you to pause and either meet that challenge with grace or shy away from it," she says.

"And when we meet these difficulties and move through them, we build up that positive belief that we can do anything we put our minds to. It creates this sense of resiliency in that we can look back and say, 'Well, a few months ago, I was losing a fly every single cast. But now I've learned to alter this and that so it doesn't happen anymore. And if I did that in one month, imagine where I'll be in a year.'"

She's also come to value the unique "groundedness" that outdoor activities like fly-fishing provide — even to individuals dealing with acute depression and addiction. Being among natural surroundings, removed from the day-to-day bustle seems to aid in restoring perspective and recharging spirits.

FISHING LICENSES

Washington:

Online at fishhunt.dfw.wa.gov or at the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife office at 2315 N. Discovery Place in Spokane ValleyIdaho:

Online at IDFG.idaho.gov/buy or at numerous outdoor recreation retail locations including Castaway Fly Shop, 1114 N. Fourth St. in Coeur d'AlenePeg Currie has witnessed similar transformations herself. The retired chief executive of Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center and Children's Hospital (and former nurse) is a self-described "farm kid" who grew up in Montana. Fly-fishing with groups like Spokane Women on the Fly has in turn enabled her to reconnect with the rustic environs that are so familiar to her. That feeling is also something that she gets to experience vicariously through others.

"One of the nuances that you don't expect is sharing it with somebody and seeing their eyes light up and their connection with nature happen. I almost think if you really never had [that connection] before, it might even be stronger because it's just such a joy to feel that when you've never felt it," she says.

Currie participates in a Spokane Women on the Fly subgroup who've dubbed themselves the Silver Sisters. Geared toward female anglers aged 55 and up, it's meant to harness the myriad benefits of fly-fishing in a way that's safe for newbies and those with mobility concerns.

"This is a very active sport, with walking and wading and being on slippery rocks or uneven surfaces. So it's a great activity for maintaining long-term balance and dexterity and muscle strength. It's really good therapy," she says. To prevent or mitigate falls, they encourage the use of special gear like wading staffs and floatation devices. The Silver Sisters also teach participants how to read the current or avoid sinking into mud.

Rosenbauer, who recently turned 70, echoes the neuromotor benefits of fly-fishing that Currie attests to. And as much as he might question the sport's meditative qualities, he's of the opinion that its relative accessibility and rich rewards make fly-fishing an ideal pastime "at all ages."

"There's no reason that anyone can't begin this," he says, "whether they're 75 or they're 15."

SPOKANE WOMEN ON THE FLY This 1,000 plus member Facebook group just celebrated 10 years of providing education and camaraderie for women interested in fly-fishing, from beginners to well-seasoned anglers.

SILVER BOW FLY SHOP in Spokane Valley, features oodles of gear and the expertise to go with it. Sign up for a one-hour private lesson to learn the basics of fly casting and get info on gear. After a private lesson, they suggest booking a guided fly-fishing trip to deepen understanding of the sport.

FLY FISH SPOKANE offers guided float and walking trips on the Spokane River as well as on local lakes (look for Stillwater Trips). These trips include use of fly rods, reels and lines. Fly Fish Spokane also offers two types of lessons. One based in a local park covers info on gear and how-to's — no fishing license is required. The other type of lesson takes place in a pond and lucky casters may even hook a fish. A Washington state fishing license is required if you are over 14 years old.

— ANNE McGREGOR