Complicated networks of arteries wind and branch throughout our bodies, constantly cycling oxygen-rich blood to our hearts, limbs and vital organs. As we age, these blood vessels accumulate plaque, restricting blood flow and increasing the risk of heart attack. Heart disease, the blanket term for such problems, kills more Americans each year than any other affliction — more than all cancers combined, all strokes, all accidents.

In 2010, nearly 600,000 people died from heart disease across the United States, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control. But despite its broad prevalence and relative preventability, heart disease continues to be widely misunderstood.

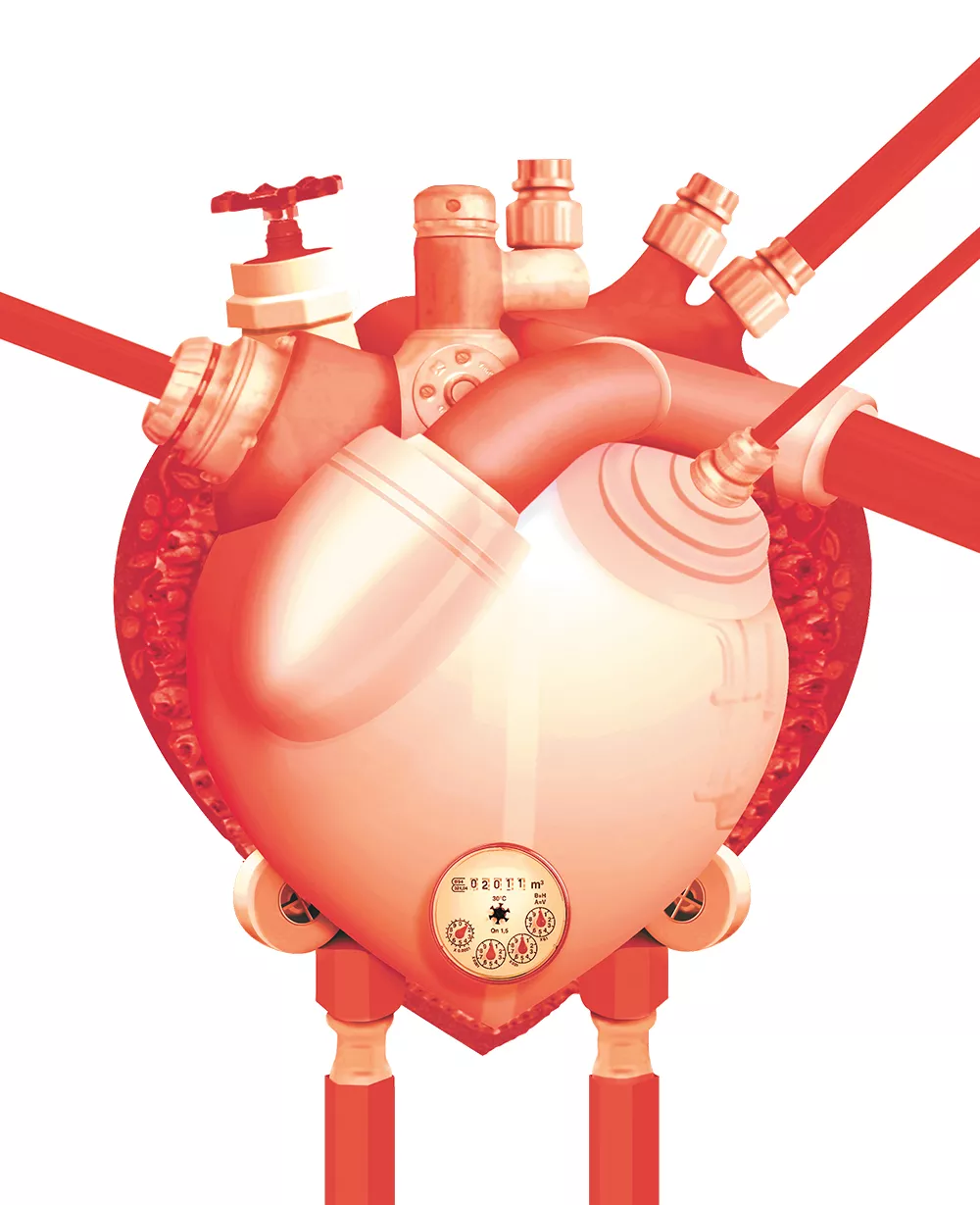

Cardiologists sometimes describe heart disease as a plumbing problem, likening blocked arteries to plugged-up pipes in need of a Roto-Rooter. But recent studies indicate that comparison tells only part of the story, and may compel patients to seek unnecessarily invasive treatments.

Dr. Michael Ring, an interventional cardiologist with Providence Spokane Heart Institute, says an oversimplified understanding of heart disease can sometimes cause a bias in patients toward excessive medical procedures. If they see heart disease as primarily a physical problem, they may assume it is best fixed with a physical procedure to clear the arteries.

"There's the perception that if you have anything wrong with your arteries you need to get it cleaned out or fixed," he says. "[Many patients] tend, if anything, to be inappropriately overly aggressive with taking care of their blockages."

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions, known as PCIs, have become the most common procedure for physically clearing arteries, pushing them open with a tiny balloon or propping them open with a metal mesh tube called a stent. More than a half-million patients undergo stent-placement procedures each year, thousands in the Inland Northwest.

Medical experts agree PCIs and stents can be lifesaving for patients with severe blockages, but some researchers, like Dr. Michael Rothberg of the Cleveland Clinic, suggest as many as half of such procedures may be unnecessary. In a recent study, he argues the plumbing analogy perpetuates a popular myth of the stent as a quick cure-all.

"Although the image of coronary arteries as kitchen pipes clogged with fat is simple, familiar, and evocative," he writes, "it is also wrong."

Stents come in a variety of sizes and designs, but most consist of a tiny metal mesh tube that collapses like compressed chain-link fencing. Implanting a stent involves snaking a balloon-tipped catheter up into an artery, usually entering through the wrist or groin area. A stent is threaded up the catheter wire to the blockage and fits around the balloon. When the balloon inflates, it expands the mesh stent until it locks open, propping out the walls of the blood vessel.

For patients suffering from severe ischemia, the suffocation of tissue due to low blood flow, stent and angioplasty procedures can provide dramatic benefits. Physically opening up the artery restores blood and oxygen immediately. Even Rothberg acknowledges stents and PCI procedures can be lifesaving in many critical cases.

Ring says the majority of local stent recipients have shown dangerous signs of poor blood flow or symptoms of angina (chest pains or tightening). A national health care survey found the Inland Northwest region has a "low usage" rate of just 5.7 PCI procedures per 1,000 Medicare patients. But the area has a higher than normal rate of PCIs on patients who have been previously screened through vascular image testing known as angiography.

"We're not going hog-wild and doing a lot of procedures," Ring explains. "We tend to be more selective. ... I think that means good care."

Critics say stents become more questionable when a patient does not suffer from life-threatening blockages or persistent symptoms. Studies have shown the elective use of stents on artery blockages of less than about 70 percent results in no significant benefit over less invasive treatments like medication, combined with healthy lifestyle changes.

While the use of stents has declined in recent years since those findings came to light, Rothberg argues the stubborn plumbing analogy creates a false impression that stents proactively prevent heart attack-causing blood clots or blockages. That assumption largely ignores the realities of inflammation and data on heart attack risks. Ring agrees with some of those concerns.

Studies suggest stents provide minimal benefit in preventing heart attacks because life-threatening blood clots often arise in sections of artery with little or no previous signs of blockage. You can't place a stent if you can't see a problem, Ring says, but patients still tend to assume a stent will ward off any future issues.

"There's that kind of inherent bias of the public, and it's a misconception," Ring says, "that being aggressive and preemptive will actually prevent a heart attack. ... [But] most heart attacks occur in areas that were not predictable."

Studies from last year indicate stents may still be overused in treating heart disease nationally, but the public seems to be accepting a more nuanced understanding. Ring, who serves with the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program for Washington state, says cardiologists have introduced new guidelines and safeguards to prevent unnecessary procedures.

National organizations have also developed an Appropriate Use Criteria, setting out the optimal conditions for implanting stents. Data shows the number of stent procedures continues to drop each year, along with the number of more invasive bypass surgeries.

In recent years, Ring says the statistics have started to turn against heart disease as procedures improve and physicians stress the importance of prevention. Annual heart-related deaths in Washington state have dropped below those from cancer, and national rates may soon follow.

"It is one of the big success stories in medicine over the past three decades," he says. "If you look at the drop in what's called age-adjusted cardiovascular mortality, it's dropped by about two-thirds."

Ring emphasizes that any diagnosis or treatment of heart disease should involve frank consultations with a cardiologist on options, outcomes and potential alternatives. Patients should read up on procedures and work with their doctors to make informed decisions.

"There are many, many factors that are involved," he says, noting, "There is some disagreement even among equally qualified, well-meaning physicians." ♦

Mind Your Diet

You heart what you eat. Registered dietitian and nutritionist Kerry Scott says a healthy diet serves as one of the best, surest ways to prevent heart disease. With so many fad diets and misconceptions, it can be easy to lose track of the essential basics of a well-balanced approach. Heart-healthy and responsible foods can take a little more thoughtfulness or preparation, but the extra time and effort pays off in the long run.

"It's not like there's broccoli at the takeout window," she says. "To eat well and to eat more whole foods takes more planning."

Eating whole foods, primarily fruits and vegetables, is one of the easiest steps. Everyone, even people in their 20s and 30s, should be aware of their cholesterol and lipid levels. Reduce saturated fats by cooking with olive oil or other plant-based oils instead of butter. Limit egg servings to less than one a day.

Two specific diets come highly recommended: the Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) plan. Both plans promote diets high in fresh produce and seafood as well as moderate alcohol intake of less than two drinks a day.

Scott recommends combining those ingredients with exercise or other activities. Even making your meals more social, such as having dinner with friends, can slow down your eating and help justify some of the investment in quality foods.

Common Terms

Atherosclerosis: The buildup of plaque along coronary arteries, leading to narrowing of blood vessels and blockages.

Angina: Chest pain, tightening or discomfort, a common symptom of narrow or blocked arteries.

Ischemia: The suffocation of tissue resulting when low blood flow cuts off the supply of oxygen to a muscle or organ.

Acute Coronary Syndrome: A significant or sudden artery blockage that dangerously reduces blood flow and may result in a heart attack.

Myocardial infarction: Commonly known as a heart attack.

Angiography: An imaging technique, like an X-ray, that shows blood flow through arteries to pinpoint blockages or other problems. The resulting image is called an angiogram.

Stent: A tiny metal mesh tube that fits inside an artery and expands to hold open a section of a narrow or blocked artery.

Angioplasty: Procedure to open or widen an artery by threading a balloon inside an artery, compressing plaque against the blood vessel walls.

PCI: Stands for percutaneous coronary intervention, a catheter procedure such as angioplasty or placing a stent to treat blockages.