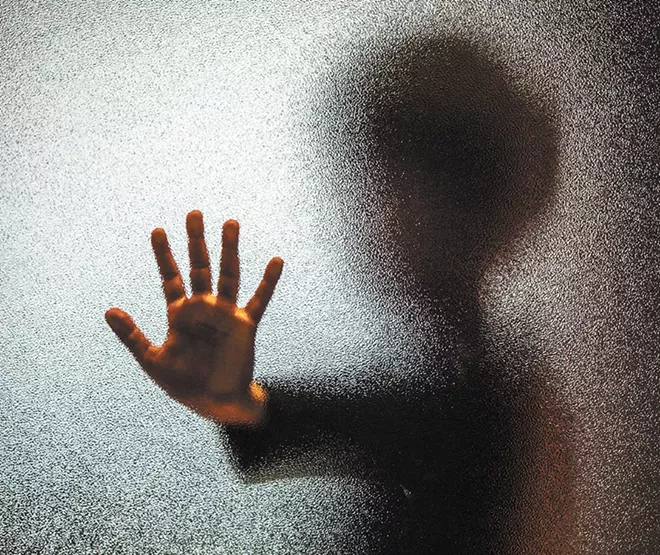

Her son has had many meltdowns. He's put holes in the wall, letting loose the aggression and irritability that mark a child with oppositional defiant disorder. But when he threatened to hurt himself and his sister, she didn't know what to do.

"He was too big for me to try to hold down," says Molly, whose name was changed to protect her family's privacy. "I took him into the doctor's office. [The doctor] said we needed to take him over to the hospital."

The emergency room has become the default destination for kids, from children to teens, needing urgent mental health care in Spokane. When faced with a crisis situation, school officials, police, parents and primary care doctors send kids to the ER, where they can be evaluated by a variety of mental health care professionals and then referred to inpatient or outpatient care.

The Spokane Regional Health District's 2008 Healthy Youth Report (the most recent research available) found one in four local youth reported being depressed for two weeks or more in the previous year, and 15 percent seriously considered attempting suicide. According to Mental Health America's 2016 report, more than half of Washington youth experiencing a major depressive episode did not receive any mental health services.

With more than a quarter of teens in Spokane County experiencing depression, and many other mental health and behavioral issues not even tallied, the system is frighteningly overburdened, parents and doctors say. The consequences are both immediate and far-reaching.

Kids in crisis can spend days — sometimes weeks — in the emergency room, waiting for an open inpatient bed. Parents fight waiting lists and limited programs for ongoing care that suits their children's needs. Some, including Molly, say that kids who move past the crisis stage can fall through the cracks.

Pediatricians describe dropping everything to help a family facing a crisis. They're trying to advocate for patients who are maneuvering through a fragmented and inefficient system.

Constantly faced with children and teens in desperate need of care, hospitals end up bearing the costs of a clogged ER and too few staff.

"Everyone gets sent to the emergency room," says Dr. Christian Rocholl, who works in pediatric emergency services at Sacred Heart. To him, this constitutes a "health care crisis."

"The mental health issues in Spokane and the Inland Northwest have really blossomed over the last few years to the point of where it's challenging to see medical patients in the emergency room," he says. "We're working at a limited capacity because we have, at any given time, half or two-thirds of our rooms being used for people waiting for mental health resources."

Coming up short

During the state legislature's shortened session that ended in March, physicians with the Washington Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics converged on Olympia to present statistics and request funding for improving mental health care for kids.

Generally, the pediatricians preached early detection and intervention. Twenty percent of children are affected by a behavioral health disorder — a catch-all term that includes mental health disorders. But only 20 percent of those children get the care they need.

"Early diagnosis and evidence-based treatment is critical to help ensure healthy development and prevent problems at home, school and with peer groups throughout childhood and into adulthood," according to WCAAP. "Pediatricians are in an ideal position to identify mental health needs early and collaborate with families and mental health professionals to support the best possible outcomes for children."

This priority was overwhelmingly supported by WCAAP members, doctors who see patients needing mental health care every day, says Dr. Lelach Rave, a pediatrician in Mukilteo, between Seattle and Everett, who is also the legislative chair of WCAAP.

Specifically, WCAAP supported funding for a program that integrates behavioral health and primary care by expanding a program at the University of Washington called the Partnership Access Line, or PAL — a phone-based consultation system for pediatricians.

The argument was that the state needs PAL Plus (as the expansion was named) because better integrated care is, so far, the best way to address unmet mental health care needs. With specialized care resources in short supply, families have to depend more on their primary doctors for access and support. Those physicians need help to step up to the plate.

In the end, the state passed legislation for a limited pilot program, but in "a very diluted form," Rave says.

Legislators readily acknowledged the need for care — and the state's stake in providing it. Nearly half of children in the state rely on Medicaid for insurance, and these children have higher rates of serious health problems. Additionally, research by the National Institute of Mental Health shows that half of all lifelong cases of mental illness start around age 14.

Objections included the state's tight budget, but also some more specific hesitations.

"I think there was also some trouble with pathologizing children," Rave says. She has a hard time understanding the discomfort, especially because there is little trouble diagnosing children with other diseases, such as diabetes. Nonetheless, "there certainly is stigma," she says.

On the front lines

Whether anyone is willing to call it what it is, everyone agrees that the system needs work. Hospital and emergency department staff look forward to more space and try to recruit psychiatrists to address the needs that come in. While not every patient needs inpatient or emergency care, that's still where most are sent. Schools, law enforcement and primary doctors who encounter a child or teen threatening to harm themselves, or acting out or fighting, generally refer that young person to the ER to be evaluated by hospital's psychiatric triage counselors.

Rocholl says he's gone to Sacred Heart administrators, looking for ways he can reach out to the community to point them to resources outside the emergency department, but progress is slow.

Adrianne Loetscher, the clinical nurse manager of Sacred Heart's adult and adolescent inpatient psychiatry, says counselors or telepsychiatrists assess each patient who comes into the ER in crisis.

They help determine whether a person needs inpatient or outpatient care — or if they can just go home. If admission is the best option, the next question is where to put them. Sacred Heart has 24 beds for teens in its inpatient psychiatric unit. Children are always admitted to Kootenai Behavioral Health Center in Coeur d'Alene.

"Demand is high and we frequently have patients waiting for inpatient psychiatric admissions," Loetscher says.

So where do they wait? In the emergency room. For days or sometimes weeks at a time, Rocholl says.

The hospital employs social workers, therapists, counselors, registered nurses, psychiatrists and psychologists to work with families. It also works with other behavioral health providers to try to plug the holes in the system, Loetscher says.

Frontier Behavioral Health operates First Call for Help (509-838-4428), a 24-hour crisis intervention hotline. Through a crisis call, children on Medicaid could be set up with a therapist or case worker. Primary care doctors also can refer patients to other agencies for counseling. In both scenarios, there are often discouraging waiting lists.

Meanwhile, Sacred Heart is trying to recruit more child and adolescent psychiatrists for inpatient services.

"Mental health is not just hospital care," Loetscher says. "Behavioral health patients and their families need a strong network and a variety of services."

The terror and the fight

Three years after a cryptic photo caption on social media uncovered her daughter's battle with depression, Andrea finds herself constantly fishing for details. "I ask her every day, 'Is the heaviness there today?' Every day I pick her up [from school] praying she'll have had a good day," says Andrea, whose name was changed to protect her family's privacy. "I'm just trying to find an answer."

But an answer is hard to find. Her high school-aged daughter doesn't know why she cut 54 lines into her forearm with a razor blade. "I think teen depression sneaks up from the smallest things. I can't pinpoint what triggers it for her, and she can't either," Andrea says.

While she has a remarkably open relationship with her daughter, Andrea remains terrified of what could happen. She's seen counselor after counselor and been through inpatient and outpatient programs. Along the way, she's run into waitlists and insurance problems.

Molly and Andrea each noticed that options after a crisis are limited and of short duration. Those later down the line can be even less attentive.

Rave sees it with her patients, as well. Long waitlists bar struggling patients from getting into acute care programs, which are based on who signs up first. "There's just not enough [assistance] to go around," Rave says.

Andrea's daughter "graduated" from one program in the summer. By Christmas, she needed help again. In February, Andrea called the crisis line after she found her daughter crying, holding her bleeding forearm.

"I knew she shouldn't be [dismissed], but they have so many people who need to get in," Andrea says.

Regular counseling visits also have been interrupted as doctors shuffle their schedules to accommodate crises as they arise. "Then it's three bumps later, I'm calling, 'I don't want to be bumped. My kid needs that weekly touch in,'" Andrea says.

Molly's son, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, or ODD, went through an inpatient program at Sacred Heart for kids with behavioral problems, called the BEST (Behavioral Education Skills Training) Program, which offered her family a chance to catch its breath but ended too soon, in her opinion.

Since then, she's spent a lot of time educating herself and finding ways to address her son's behavioral disorder on her own. She notes, "You have to be really, really bad or you don't get any help. You have to fight extremely hard just to get listened to." ♦

Smart Help from a Smartphone

Lengthy waits for treatment for mental illness are common. And sometimes people are reluctant to even seek help. MoodTools is a smartphone app that offers immediate assistance. Comprised of six evidence-based tools, it offers tactics to "combat depression and alleviate negative moods," according to the recent Duke University grads who developed it. The free app, created in collaboration with mental health professionals, includes a depression self-test and symptom tracker, a Thought Diary that incorporates Cognitive Therapy principles, a Safety Plan to help prevent suicide, suggestions for activities and links to helpful websites, including TED talks and guided meditation. Designed mostly for assisting with clinical depression, the app's developers note that while it is not a substitute for traditional therapy, it may also help people suffering from anxiety, PTSD, OCD and seasonal affective disorder.

— ANNE McGREGOR

Help For Parents

It's not easy helping a child facing behavioral or mental challenges. Parents and caregivers of these kids can find much-needed support and help at a family-to-family program run by the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Spokane.

The NAMI Basics course covers everything from diagnosis and treatment to how to work with schools. "People take the course because they're going to help their children by learning all they can about it," says Ron Anderson, vice president and program director for NAMI Spokane. And there's lots of support available because all the instructors have experienced life with a child who has or could have a mental or behavioral illness.

"The underlying factor is how to take care of yourself... because without them, their children's care won't be nearly as good," Anderson says. "We help them understand what they can fix, and what they can't fix."

— TARYN PHANEUF

Visit www.namispokane.org or contact Ron Anderson at 509-590-9897 or office@namispokane.org. The 15-hour course is free, offered in the fall, and occurs over three Saturdays.

Overcoming Stigma

In Washington, pediatricians pursuing public funding to better integrate behavioral and primary care ran into legislative resistance related to diagnosing children with serious mental health disorders and prescribing medication and treatment. In a sense, that resistance might mean kids who need care won't get it. But they also have a point.

"I think the concern of putting a label on a kid is a real one. It has ramifications... It definitely has an affect on people's ability and interest in accessing care," says Annabelle Gardner, a spokesperson for Young Minds Advocacy in San Francisco. "It's not as black and white as, 'Well, what matters is that we need to get these kids care,'" she says. "In reality, there's a lot of things that matter in a kid's life. It's not fair for a system to decide what matters more."

Many kids in the mental health system already have other labels attached to them, like "foster youth" or "delinquent." The labels can impact the way they see themselves and the choices they make as a result. And in some cultures, a diagnosis of mental illness carries considerable baggage.

In one attempt to normalize mental health care as part of routine medical care, pediatricians have embraced a new standard of care requiring them to begin screening patients for depression at age 12.

From contraception to sports injuries, pediatricians have a lot of ground to cover during visits with their patients, says Dr. Lelach Rave, a pediatrician in Mukilteo. Adding in depression screening can help reveal issues that aren't as obvious, but shouldn't be ignored. "Hopefully we'll be catching more kids who need help," Rave says.

— TARYN PHANEUF