It happened to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and The Lord of the Rings for being "unwholesome" and "ungodly." The Catcher in the Rye was "anti-white," and To Kill a Mockingbird was "anti-black."

Pulling provocative books off library shelves seems like a vestige of a more uptight culture — something that happened 50 or 100 years ago. But concerns over what kids read is very much a contemporary issue.

The American Library Association uses the term "challenge" to describe "an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group." While many young readers have grown up enthralled with The Hunger Games trilogy and the Harry Potter series, those books are among the most challenged of the past two decades — denounced for being "anti-ethnic," "violent," "anti-family" and even "satanic."

So who's in charge of deciding what books kids can access?

"Parents have every right to ask us to reconsider whether a book should be on our shelves," explains Gary Simundson, a high school librarian and adjunct professor for Central Washington University's Educational Library Media program. But complaints don't always lead to a formal challenge, and even then there's no guarantee a book will be whisked away.

If a parent is upset about a book, "I tell them, 'Thank you for your concern. I'm glad you brought this to me; we try to have a balance, and your child did exactly what she's supposed to do by deciding she didn't want to read it,'" Simundson explains.

"If they are really upset still, I ask them, 'What would you like to see happen?' They usually want it taken off the shelf, so I tell them, 'There is a formal process we go through. I can get you the paperwork.'"

The paperwork varies little from school district to school district, as most follow the basic tenets of the ALA's Library Bill of Rights. Spokane Public Schools' form is buried at the end of the seven-page "Criteria for the Selection of Instructional Materials" and asks complainants for a thoughtful statement of objection and "understanding of the teaching and instructional context within which the material is used."

"They will often take the paperwork, and it doesn't go anywhere," Simundson admits.

Defining "Objectionable"

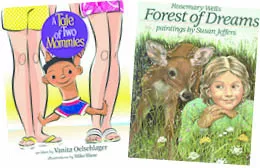

It's not just sex and violence that irks parents. "There's a children's book by Rosemary Wells, called Forest of Dreams," explains Yvonne Davis, the librarian at Jefferson Elementary School. "It's a semi-classic. The cover is a little girl with a deer, and this little kindergartner had checked it out and brought it back in to me and said, 'My mom wants to know why you have God in the library.'

"I told her, 'I'm not sure what you mean. The book is about nature, and life,'" says Davis. "I knew it mentioned God a few times in the text, but honestly, I wasn't sure where to go with her. 'We have lots of different books about lots of different ideas,'" she told the 5-year-old with a tiny, furrowed brow. "'If that's not a book you like, then you don't have to take it.' Davis recalls saying.

"If she'd been older, I could have explained, 'There's lot of books about God over in the 200 section of nonfiction' [the Religion section]. And who sends a kindergartner to hash out an issue?" Davis says, laughing.

She admits that all librarians grapple with offering equitable access while still being mindful of the sometimes contrasting desires and needs of adolescent readers. "My middle school colleagues wonder if 12- and 13-year-old readers need to read plot lines of characters in their late teens. We all agree there's time for all that later. ... But then, we don't want to restrict access to the more voracious and mature readers. It's a conflicted thing."

Telia Sherwood, who runs two elementary school libraries for Spokane Public Schools, says the most recent challenge she received was about a picture book called A Tale of Two Mommies. "I love that book because it's not gender-based," she says. "It doesn't even show their faces. This little boy had brought it home because he liked the pictures. The parents, at first, wanted me to take it off the shelf," Sherwood explains. "I told them we have families of that makeup in the building, and in society, and kids want to see what it's like."

Sherwood stayed calm and diplomatic. "I said, 'If you don't want your child exposed, that is your prerogative,' and I referred to the policies, which state, 'The library is a place for fair and equal rights of all students.' If you bring it back to the policy, there's not much they can do unless they want to challenge the policy, and that's not under my jurisdiction anyway."

Sometimes it's not so much the content as the general impression that a book isn't, well, very literary, that leads to a challenge. Simundson has testified twice in the past few years to avoid a removal; once to defend the Goosebumps series. "Even if books don't have literary merit, if reluctant readers are reading them, then education is happening," he says.

Diane Brooks — quick to admit she is a "hovering helicopter" parent who restricts her kids' access to television, social media and music — says she would prefer that librarians filter reading material far more than they do. The family lives in the Tri-Cities, and now that Brooks' daughter is in eighth grade, she says it's getting harder to monitor her access to information. "I don't want to make choices for other parents, but what I continue to discover is that most parents don't know what their kids have access to in the library. And that teachers tend to go off of other teachers' advice, and they don't know everything that's in the books, either."

Sherwood says that if she knows a high-quality book is controversial, she reads it. "If I have to fight for it, I need to know why I bought it," she says. "And the library is a place for all sorts of viewpoints. There are so many things we're not talking about in students' lives, and if they are relating in a piece of literature, then that is fantastic. I'm willing to push boundaries more so than a lot of librarians."

Room For Discussion?

Spokane-based juvenile fiction author Chris Crutcher, whose novels deal with themes of abuse, neglect and unexpected heroism, says it's not a sense of rejection or loss of income that hurts when his books are removed from schools. It's the loss of conversation.

"You're not censoring the book ... what you're doing is stopping discussion about that book in the place where you'd think we'd want to have discussion, which is school," he says.

Since 1995, nearly every one of Crutcher's 13 novels has been challenged. A few have been removed. According to his website, in 2009 a teacher in Kentucky was fired over having his book, Deadline, in her curriculum. (The district superintendent was the one of the complainants.)

"I'm so used to the struggle that I don't have a lot of personal feeling when one of my books gets challenged," he says. "The one thing you do know as an author is that if your books are getting challenged or banned, that you have a significant following. Otherwise your books would never blip the censors' radar."

Although "reconsideration" may sound more thoughtful or diplomatic than "censorship," Crutcher, Sherwood and the ALA believe there's no distinction. "When you decide to either not put a book on the shelf or remove it, it's the same thing," Sherwood says. "The library is supposed to be a place where children's worlds are expanded. When a book is pulled, it fundamentally makes their world narrower." ♦