For most of us, the workday starts when we reach the office. For Dr. William Sayres, work starts when he flips on his kitchen light. As the 52-year-old family physician prepares breakfast in his Valleyford home, he often gets calls from nearby neighbors needing a little medical assistance. How about a quick check on Mom? Could he answer a couple of quick questions about a prescription?

Sure, he says. He’ll come by. Making house calls is just a part of what he does. “It’s fun, and families are so appreciative,” he says.

Stopping by the home of an ailing patient is only a fraction of what Sayres, a Spokane family physician, considers his job description. He cares for people at the end of their lives. He nurses the chronically ill. He delivers babies. He patches up athletes. (Two of his patients won their age groups this year at Bloomsday.)

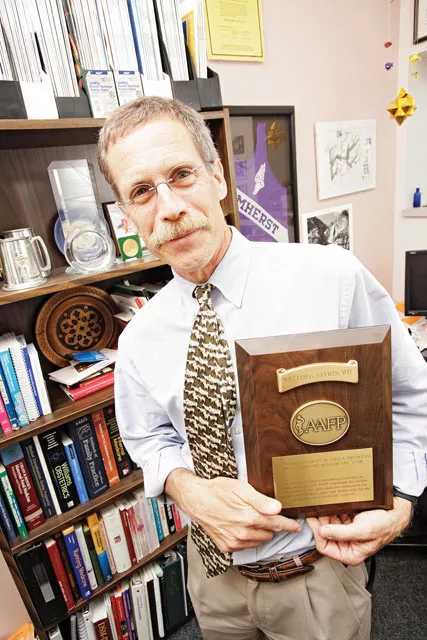

It’s that devotion and willingness to acquire a range of skills that got him noticed by the Washington Academy of Family Physicians, who named Sayres the 2009 Family Physician of the Year — an award that doctors on the east side of the state rarely receive.

After a 15-mile bike ride from his home to the Group Health Riverfront Medical Center (where he serves as clinical chief), Sayres talks about being a family physician with the zeal of a fresh-faced med student, even though he’s been in the profession for 30 years.

With no doctors in his family, Sayres had few plans for growing up to become one. However, after completing his undergraduate degree in German, he found himself drawn to a career that would enable him to continue learning through his life. Preferably one with a social mission. How about being a doctor?

While going from speaking German to the examining room might seem like a big jump, Sayres says it makes sense: “There’s a long tradition on the East Coast of medicine being a Renaissance tradition. You could bring the world into the examining room with a patient,” he says. “To look and simply see these pre-medical students studying all the time — that is so far from what it takes to be a good doctor.”

As a family doctor, Sayres is part of the medical field that is in dire need of revival. A New York Times article this April examined the nervousness of the Obama administration over nationwide doctor shortages, but also over the waning number of primary care providers. Sayres says only about 20 percent of med school graduates are choosing to go into family practice. Why?

Primary docs don’t earn nearly as much as specialized doctors. Sayres says that to a medical student who owes hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans, it makes sense to go for a job that might pay off that debt more quickly.

“When [young doctors] look at primary care, there is this perception that the hours are long. I see an attention to their personal lives and their families. There’s an unwillingness to sacrifice,” he says. “There’s this perception that primary care doctors work too hard — which they do.”

To specialize — say, as a cardiologist — means to learn “the most you can about a finite area,” Sayres says.

In primary care, doctors don’t specialize, but they are the front lines of the medical field.

“You’ll never be the best. [Young doctors] think, ‘Why deal with all of this other mess —the chaos of general practice?’” Sayres says. “There’s this huge conspiracy that if you go into family care, you are this intellectual pariah.

“The way I look at it, my job is very similar to academics. I try to publish a paper every couple of years,” he says. “You just can’t get tired of learning.”

Sayres says general practitioners must be the Renaissance men and women of the medical field — the people most willing to continue expanding their medical knowledge throughout the course of their careers. They are communicators. They’re mediators. Mentors, even.

And sometimes, to be a doctor is to simply be an ear for a patient, there to listen to what’s going on. That’s something that Sayres says has taken him all this time to learn.

“One of the hardest things for doctors to do is listen. After 30 years in this, I feel like I can step back, take a breath and listen,” he says, smiling.

Perhaps patients are drawn to Sayres because of his ability to listen to them. At the end of the day — a day full of meetings and babies and illness after illness — Sayres hops on his bike and rides the 15 miles home again. And the neighbors who watch him ride back to his home know that he’s a busy guy. They also know that he’s OK with 5 am phone calls.