When you pass by the First Interstate Center for the Arts on Spokane Falls Boulevard, you see a timeless structure of concrete and glass — modern and enduring. Great architecture can make a building feel both new and like it's been there forever. It might surprise you to know it's turning 50.

Wait, isn't this also the 50th anniversary of Expo '74? Yes, they share a birthday because the Washington State Pavilion (aka the Spokane Opera House, now the FIC) was built for the world's fair. According to historian Bill Youngs, the foremost authority on all things Expo '74, "it's the most important architectural residual of the world's fair."

It's hard to argue with that. In 1974, the theater kicked off with a full slate of world-class performances, and it has continued attracting shows like Hamilton, Les Mis and Cats in the years since.

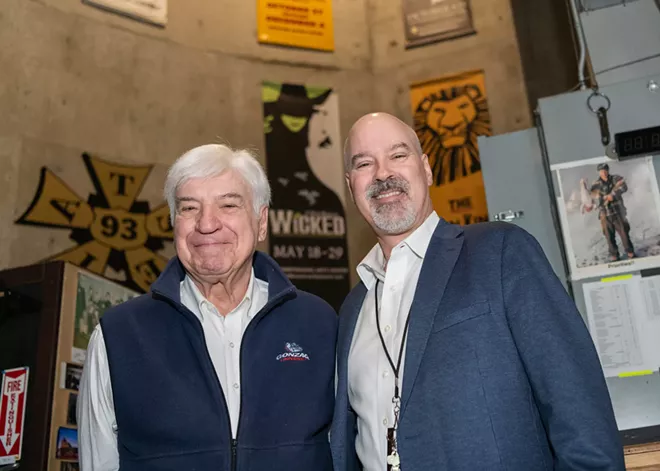

There's a connection across all those years that's alive today in Spokane's Kobluk family. Mike Kobluk was one of the first dozen employees of Expo '74; he was charged with filling the entire schedule, May through October, with dazzling entertainment. His son, Justin, has been president of the Best of Broadway series since 2019, filling the very same theater with must-see shows. Like father, like son.

Mike, his wife, Clare, Justin and I met inside the theater to trace the serendipity of it all. Up on the stage, the house lights reveal the simple beauty of the space.

"Since growing up, I'd be backstage, so I've seen it up close from the back end and from the front end," Justin says. "It's always been part of our family."

Meanwhile, Mike and Clare stand silently, taking a long look out upon row after row of red seats, rising as they recede into the balconies. I can only imagine the flood of memories.

"I kept hearing about King Cole and how he wanted to do a world's fair," Mike recalls. "I knew right away that was the job I wanted. I wanted to work for the world's fair, and I wanted to work for King Cole. I'd see him around town at that time, and I guess I'd just accost him about it."

And it worked! Cole, the "Father of Expo," hired Kobluk as Expo's manager of special events and director of performing and visual arts. Kobluk had just finished his degree at Gonzaga and was working in the alumni relations office. But he was ready for some excitement like the kind he had been steeped in for more than a decade before he came back to Spokane.

It all started when he and two friends from the Gonzaga Glee Club — Chad Mitchell and Mike Pugh — went to New York City in the summer of 1959 to see if they could make a dent in the growing folk music scene.

And it worked! In the era of the Kingston Trio and early Bob Dylan, the Chad Mitchell Trio took off. Hit records and world tours followed. Joe Frazier would replace Pugh; later, John Denver joined the group; Roger McGuinn played guitar; and Harry Belafonte championed their music. College would have to wait.

After a show in Mexico City, an exchange student from Texas caught Mike's eye; they started dating, but he'd have to convince her parents of the prospects of a humble folk musician. The Trio's appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show was apparently enough, and Mike and Clare were married. Soon came kids — daughter Lydia, who now lives in Tacoma, and the twin boys, Justin and Gerry, a Spokane attorney. A young family and life on the road did not mesh, so Mike left the trio in 1968. After 18 months in New York as a promoter, it was back to Spokane. His mom had never given up on pestering him to finish his degree, as moms will do.

Which brings the story back to Kobluk semi-stalking King Cole around town. The truth is, he was extremely well qualified for the job, with connections throughout the industry. Just four months before opening day, when the list of bookings was still pretty thin, he was interviewed by the newspaper.

"I told them I thought it would be 'The Entertainment Capital of the United States' for six months. Of course that's what they put in the paper."

The interesting thing about an opera house is that you have to tune it. It's like a musical instrument...

The pressure was on. Earlier, Kobluk had sent handwritten letters to mayors in cities across America, asking them to lend their entertainers to the effort.

And it worked! "One day," he says, "we got a letter back from the mayor of Los Angeles. They wanted to be a part of it — in fact, they wanted to bring the LA Philharmonic with Zubin Mehta. And they wanted to open the fair!"

When word got out about the LA Phil, the engagements started flowing. Bob Hope, old friends John Denver and Harry Belafonte. One letter carried the looping, florid signature of Liberace, who committed to six shows around the Fourth of July. (Kobluk was also booking Expo shows into the Spokane Coliseum.) It became a jam-packed showcase of pure 1970s pop culture — the Carpenters, Olga Korbut, the Amazing Kreskin.

"And," says Mike with a big smile, "we made over $300,000 in profit."

His reward? A full-time job, as somebody was going to have to fill this new building with entertainment after that magical year. He stayed on for nearly three decades, retiring in 2002. In a hallway backstage, there's a plaque that reads: "The House that Mike Built."

The struggle to get the Opera House rolling as a real venue after the fair is another story, but suffice to say a lot of amazing things grew from the seeds planted in 1974: TicketsWest, the Spokane Convention Center, the Spokane Arena, the Spokane Public Facilities District (directed for 16 years by Kevin Twohig, who started his own career working Expo shows). And, of course, there's the Best of Broadway series that Justin leads today, which in its 36 years has brought in 1,843 performances with 3.3 million seats filled. All that from one building that had its own dramatic backstory.

"It was not certain the Opera House would get booked," Mike says. "But you know, for a while it was not certain it would even get built."

When King Cole was asked what the money would be used for, he answered, "I don't care... as long as it's in the shape of an opera house."

While the U.S. Pavilion, recently renovated and still in the heart of Riverfront Park, was a gift from all of these United States, over in Olympia Spokane had to make its case. Leading citizens and business leaders stepped up to help, with local business titan Luke Williams taking point. Ultimately, they secured $7.5 million, with $2.9 million more the next year to fulfill Williams' goal of adding convention center space. Another $1 million was raised locally under the leadership of future mayor Vicki McNeill.

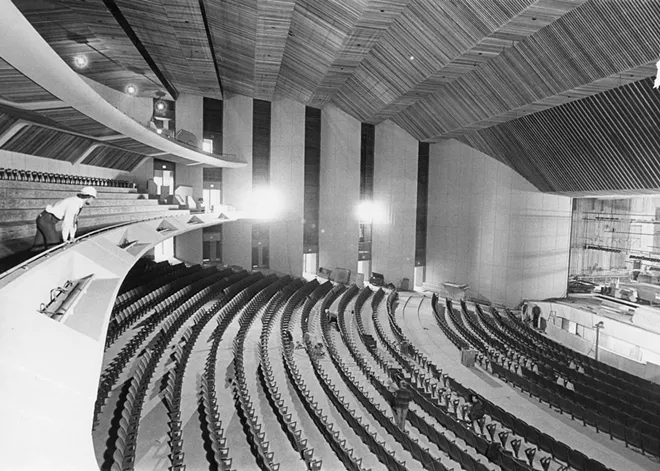

Local architectural phenom Bruce Walker and his partner John McGough won the contract to build it. As a Spokane kid at the University of Washington, Walker was disappointed when he found out they did not offer a cartooning degree, so he chose architecture. He took a break from college to defend democracy in places like Iwo Jima and the Philippines. Upon his return, he finished his degree, then went to Harvard to study under the legendary Walter Gropius. He worked on the Washington Water Power building with Ken Brooks, and later designed five buildings on the UW campus, along with their Red Square plaza; Walker's firm became Integrus.

Yes, Walker was a rock star of his profession — but having never designed a theater, he was intimidated. "It's like designing a kitchen for a cook you don't know," he commented.

An early innovation was to make it bigger, going from a planned 1,300 seats to 2,600. Acoustics, a key element of any good theater, were another challenge. While at Harvard, Walker took a class on acoustical engineering at MIT (of course he did), but he also knew enough to bring in a top expert from Los Angeles to consult. The wooden slats you see in the ceiling today are a part of their novel acoustic design.

"The interesting thing about an opera house," Walker told Bill Youngs for his 1996 book The Fair and the Falls, "is that you have to tune it. It's like a musical instrument in the sense that it has a sound to produce."

The final tests and tweaks, Walker said, were conducted when somebody brought in a bunch of cassette tapes they'd blast out to test the sound from different seats. The voice they chose? Neil Diamond's.

Justin Kobluk says he hears again and again from touring productions that the space has stood the test of time; Walker's design works for all kinds of cooks he did not know. Along with the sound, producers love the size of the stage — much larger than the theaters in New York where these shows make their debut. The building has even set records for the load-in, load-out times for many shows. (Yes, the theater world keeps track of such things.)

For its opening weekend back in 1974, the Washington State Pavilion welcomed the LA Phil on the evening of opening day — Saturday, May 4. On Friday night, May 3, it was the Spokane Symphony that got to officially christen the space, under the direction of Donald Thulean.

Justin would have been about 7 at the time — just old enough to know that mom, dad and the other grown-ups were up to something big.

While Justin was studying at UW in the 1980s, the Chad Mitchell Trio was doing a reunion tour. He decided he would surprise everyone by making a trip out to a show in New York City. He arrived early in the day and jokingly told the guy at the door he was with the band. Great, the man said, maybe you can help with these, pointing to a box filled with square little plastic cases. Today we know them as CDs, but at that time they were a strange new innovation.

"He didn't know what to do," Justin recalls, "so I jumped right in there and sold the merch. After the show, I settled up, filled an envelope with cash and delivered the band's share to the Trio. Right there, I felt like, 'I can do this.' I just loved the feeling of being part of it."

After graduating, Justin let his parents know his post-college plans. They were likely among the tiny minority who would support what he had in mind: following the Rolling Stones to sell T-shirts.

In fact, it was more than selling t-shirts; at age 22, Justin was managing the merchandising behind major tours like the Stones, Janet Jackson and Garth Brooks. That led him to the Midwest where he helped open and manage a new arena at Wright State University in Ohio. He came back West to run the events at the Tacoma Dome, then worked for the Seattle Supersonics, then helped launch the new Angel of the Winds Arena in Everett. Finally, 25 years after leaving Spokane, he came back to help develop the entertainment program at Northern Quest Resort & Casino, including the design and build of the BECU Live! outdoor amphitheater.

The full circle was closed in early 2019 when he took the reins at Best of Broadway, toiling to fill the very same theater with joy, laughter, tears and ovations — just as his dad did all those years ago.

The time away has brought perspective, Justin says, especially appreciating more fully the spark that Expo '74 lit for a city that has made great strides since the time he grew up and moved away.

"Today, Spokane, without being a big city, has everything a big city has," he says. "The success of this building, with the world watching, that's what tipped everything over and allowed us to take the next steps — the Arena, we now have the Podium, the Convention Center. I can't imagine how any of this would ever be done today; what it took to accomplish all of it is enormous."

Here 50 years later, it's hard to describe the audacity of Expo, or the scope of its legacy. "Enormous" is a good start. For many, like the Kobluks, it's long been woven into their life story; for others, it's Expo's delightful mystery-you-can't-quite-solve vibe that has resonated across so many decades.

Mike Kobluk, one of the ringleaders of Expo's merry band of dreamers, has an explanation: "Expo," he says, "it was truly a miracle."